From descriptors to machine learning interatomic potentials: a review of AI-accelerated electrocatalyst design

Abstract

Electrocatalysis underpins key energy-conversion reactions, such as carbon dioxide reduction and oxygen evolution/reduction reactions; however, catalyst screening based on density functional theory (DFT) is constrained by rapidly escalating computational costs. In recent years, coupling machine learning (ML) with DFT has opened a promising path around this bottleneck. This review synthesizes recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI)-accelerated electrocatalysis along three pillars: descriptors, ML techniques, and machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). First, we compare the acquisition strategies for three classes of foundational descriptors: intrinsic statistical, electronic structure, and geometric/microenvironmental. Second, we summarize how algorithms such as tree ensembles and kernel methods perform across varying feature dimensionalities and extrapolation regimes, and discuss recent research on customized composite descriptors in the context of these models. Third, we categorize mainstream MLIPs into three families: “general graph-network”, “symmetry-equivariant”, and “extreme-efficiency”. We then compare their trade-offs in accuracy, computational cost, and scope of application. Finally, we highlight limitations of available datasets and propose practical paths forward.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

As the world transitions toward a low-carbon economy, electrocatalysis has become crucial in enabling key energy conversion reactions, such as the carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR) and the oxygen evolution/reduction reaction (OER/ORR)[1]. Density functional theory (DFT) has long been the workhorse for mechanistic insight and catalyst screening; however, its computational cost grows steeply with system size and structural complexity, hindering the exploration of large configurational space. Machine learning (ML) is reshaping the discovery pipeline for electrocatalytic materials. By extracting informative representations of structure and chemistry - and using statistical and neural network models to approximate atomic interactions - ML can deliver results of respectable accuracy at a fraction of the cost of quantum mechanics calculations. Critically, model performance depends on two factors: (i) how to efficiently and accurately capture structural and electronic information, and (ii) how to select suitable algorithms for specific tasks and data regimes. Accordingly, this review surveys recent methodologies in electrocatalysis along three dimensions - descriptors, ML methods, and machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) - to provide a coherent picture of how ML is accelerating progress in the field.

ML METHODS FOR ELECTROCATALYSIS

ML methods used in electrocatalysis range from tree ensembles and kernel models to deep graph networks and MLIPs. These families differ in their prediction targets, feature usage, and the trade-offs among accuracy, data requirements, and inference costs[2]. Recent reviews summarize this landscape and common workflows in which models support high-throughput screening, mechanistic interpretation, and surrogate atomistic simulation. Below, we synthesize reported results from the literature and highlight when different method families tend to work well in practice.

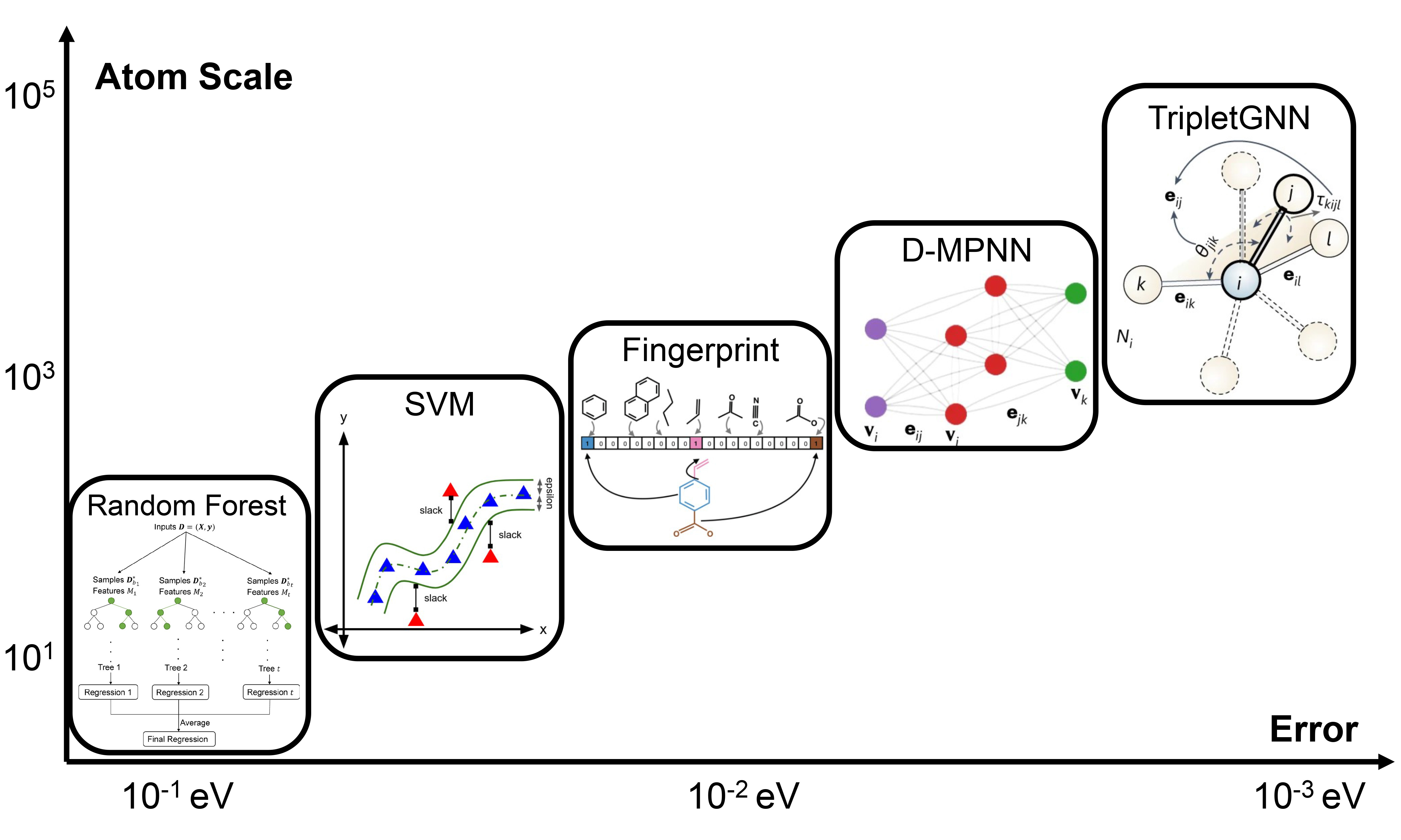

The model choice of ML directly determines predictive accuracy, interpretability, and extrapolation. The literature shows that the two most common routes - tree ensembles [e.g., gradient boosting regressor (GBR), random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting regression (XGBR)] and kernel methods [e.g., support vector regression (SVR)] - excel in different situations. Wang et al.[3] compared GBR, RF, and SVR on 43 copper (Cu) single-atom alloys [single-atom catalysts (SACs)] using the same 12 descriptors: GBR performed best for CO adsorption [test root-mean-square error (RMSE) = 0.094 eV], ahead of SVR (0.120 eV) and RF (0.133 eV). When extrapolating to dopant metals absent from the training set, accuracy varied by element; adding even a small number of target cases significantly improved transfer performance. Tree ensembles also worked well for predicting the adsorption of CO2, CHO, and related intermediates in other systems[4,5]. These results indicate that, with sample sizes in the hundreds, moderate feature dimensionality, and highly nonlinear structure-property relations, the multi-split nature of ensembles can automatically capture higher-order interactions and deliver a competitive cross-system extrapolation[3]. In a small-data setting, kernel methods can be particularly effective. Tamtaji et al.[6] used an SVR with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel to model hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), OER, and CO2RR overpotentials with about 200 DFT samples and ~10 features, achieving test coefficient of determination (R2) up to 0.98. These results highlight the efficiency and robustness of kernel methods when feature spaces are compact and physics-informed.

Taken together, in a medium-to-large sample regime such as the Cu SACs case [N = 2,669; p = 9-12, where N denotes the number of samples and p indicates the number of features (predictors)], GBR outperformed SVR and random forest regression (RFR)[3]. In a small-sample setting with strongly physics-informed features, such as the FeCoNiRu case (N = 200; p ≈ 10), a Support Vector Machine (SVM) achieved a test R2 of 0.977 with low error[7]. These two cases illustrate how sample size and feature design jointly determine the preferred model family.

ELECTROCATALYSIS DESCRIPTORS

General-purpose foundational descriptors

In ML, input descriptors for electrocatalysis are broadly obtained via three routes: intrinsic statistical, electronic structure, and geometric/microenvironmental. The intrinsic statistical properties rely on fundamental elemental properties. Such descriptors typically include elemental composition, valence-orbital information, ionic characteristics, and other simple attributes that require no DFT calculations and are easily obtainable. For example, Huang et al.[8] used Magpie to compute 132 elemental attributes and then selected 14 properties as descriptors for model training. When paired with simple ML models, such descriptors can accelerate screening relative to DFT by 3-4 orders of magnitude[9]. This strategy is system-agnostic and has been applied to dual-atom catalysts (DACs)[4], single-atom alloys[3], and related materials. Although intrinsic statistical descriptors are less physically interpretable, their extremely low computational overhead makes them the lowest-cost option in “coarse-screen → refinement” workflows.

The second route, electronic-structure descriptors, covers orbital occupancies, charge distribution, spin, electron affinity, magnetic moments, and other related quantities[6]. Chen et al.[7] proposed the non-bonding d-orbital lone-pair electron count (Nie-d) as a descriptor for rapid screening of nitrogen reduction reaction (NRR)-active electrocatalysts. Zhao et al.[10] further showed that a combined metric of “spin magnetic moment + d-band center (εd)” quantitatively explains the HER volcano relationship on graphdiyne (GDY)-supported SACs. By encoding reactivity at the electronic level, these approaches enable ML models to grasp the essential catalytic characteristics more accurately; however, they typically require DFT and are thus best suited to fine screening and mechanistic analysis.

The third route considers local geometry and microenvironment. Mou et al.[11] adopted the metal second ionization energy (IE2nd) and the area of the M-O-O triangles (SM-O-O) as descriptors within a zirconium 1,4-dicarboxybenzene metal-organic framework (UiO-66) framework to predict pathway limiting potentials with high accuracy: when switching to other substituents, the error remained below 0.1 V, indicating a strong transferability of the proposed descriptors. Das et al.[4] introduced interatomic distances and a surface-layer site index, while Zhao et al.[10] employed asymmetric local strain and coordination vacancies as geometric-environment descriptors; both improved model accuracy. Overall, geometric and microenvironmental descriptors can accurately capture structure-activity trends across diverse supports and complement the two classes above.

In summary, intrinsic statistical descriptors enable rapid and wide-angle exploration of chemical space; electronic descriptors connect directly to reactive orbitals; and geometric/microenvironmental descriptors distill local structure-function relations in complex environments. By integrating all three - first using inexpensive intrinsic statistical descriptors to identify “uncertain regions,” and then incorporating key electronic or microenvironmental information - accuracy can be maintained while minimizing DFT costs, enabling a closed-loop, high-throughput pipeline of “coarse screening → refinement → validation”.

Customized composite descriptors in ML

In recent years, general-purpose foundational descriptors have been instrumental in ML-based electrocatalyst research. Yet as systems grow more complex and the variety of metallic active sites increases, activity is often co-governed by multiple electronic and geometric factors. To address this, researchers increasingly design customized composite descriptors and pair them with lightweight ML algorithms to reduce feature dimensionality while improving predictive accuracy.

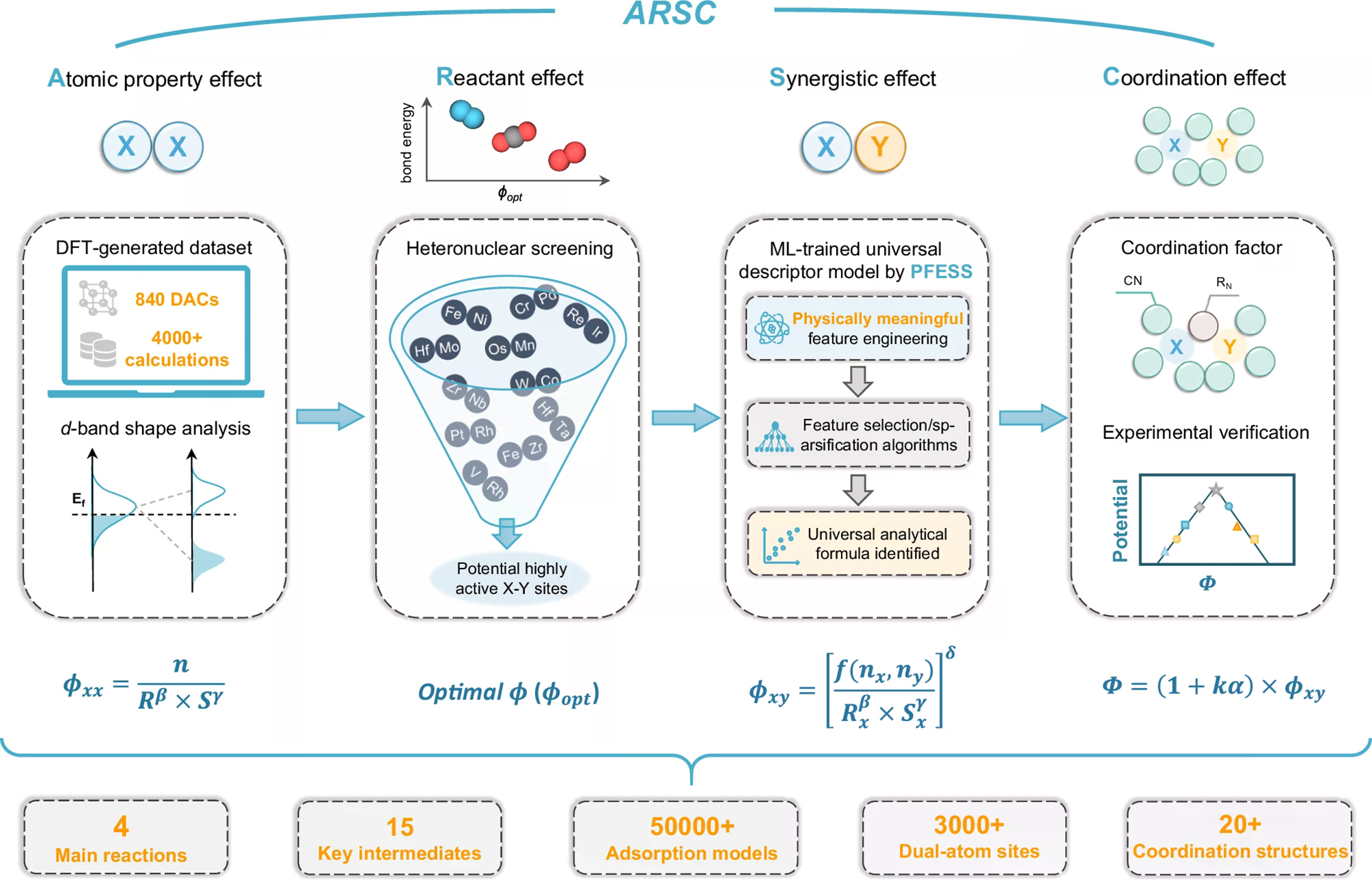

Lin et al.[12] proposed the ARSC descriptor for 840 transition metal DACs. They decomposed the factors affecting activity into Atomic property (A), Reactant (R), Synergistic (S), and Coordination effects (C). Using physically meaningful feature engineering and feature selection/sparsification (PFESS), they derived a one-dimensional analytic expression that predicts adsorption energies of ORR, OER, CO2RR, and NRR intermediates. The model achieved accuracy comparable to that of ~50,000 DFT calculations while training on fewer than 4,500 data points [Figure 1]. Sun et al.[13] studied O-coordinated single-atom nanozymes (SANs) with 27 atomic-orbital features ranked using XGBR. After recursive feature elimination, they retrained the models with only three variables [εd, εp(O), and εp(sub)] and still achieved high accuracy (mean absolute error (MAE) ≈ 0.08 eV). Building on this, they proposed the FCSSI descriptor (first-coordination sphere-support interaction), which encodes two electronic coupling channels - metal-to-support and coordination-to-support - thereby reducing dimensionality while preserving key information.

Figure 1. Workflow of ARSC descriptors generation: (i) ϕxx, a primitive descriptor mapping atomic-property effects via d-band shape; (ii) ϕopt, a reactant-effect-based screening for heteronuclear DACs; (iii) ϕxy, ML descriptors of synergy built from ϕxx with physics-guided features and sparsified selection; and (iv) Φ, a universal model quantifying coordination effects with experimental verification. Reproduced with permission from Lin et al.[12] (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0); no changes made. ARSC: Atomic property (A), Reactant (R), Synergistic (S), and Coordination effects (C); DFT: density functional theory; DACs: dual-atom catalysts; PFESS: physically meaningful feature engineering and feature selection/sparsification; ML: machine learning; CC BY-NC-ND 4.0: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Customized composite descriptors preserve chemical interpretability, reduce input dimensionality, and lower the computational cost of DFT calculations. However, their limitation lies in specificity: being finely tuned to specific chemistries or tasks, they may not transfer seamlessly to new materials and reactions. A promising direction is to combine these composite descriptors with graph neural networks (GNNs) and symmetry-equivariant models to distill more universal reactivity descriptors. This would further accelerate exploration and design across the high-dimensional space of catalytic materials.

MLIPS-RELATED MODELS

Mainstream MLIPs

MLIPs have recently achieved notable advances in structure design and high-throughput screening. We classify modern MLIPs into three families: general graph-network potentials, symmetry-equivariant potentials, and extreme-efficiency potentials. By equivariance, we mean a practical rule: when atomic coordinates are rotated, reflected, or translated in three-dimensional space (e.g., elements of the E3 group), scalar outputs, such as energies, remain unchanged, while vector and tensor outputs, such as forces and stresses, transform in the same way as the input[14]. General graph-network potentials enforce invariance at the energy level using rotation- and translation-invariant local features and obtain forces and stresses by differentiating the energy; their internal message passing is not required to be equivariant at every layer. Symmetry-equivariant potentials enforce E3 equivariance by design throughout the network, ensuring that intermediate features and outputs follow the correct transformation rules. This often improves data efficiency and geometric generalization, albeit at an extra computational cost. Extreme-efficiency potentials relax some of these constraints to maximize speed and scale while keeping sufficient accuracy for screening and large systems.

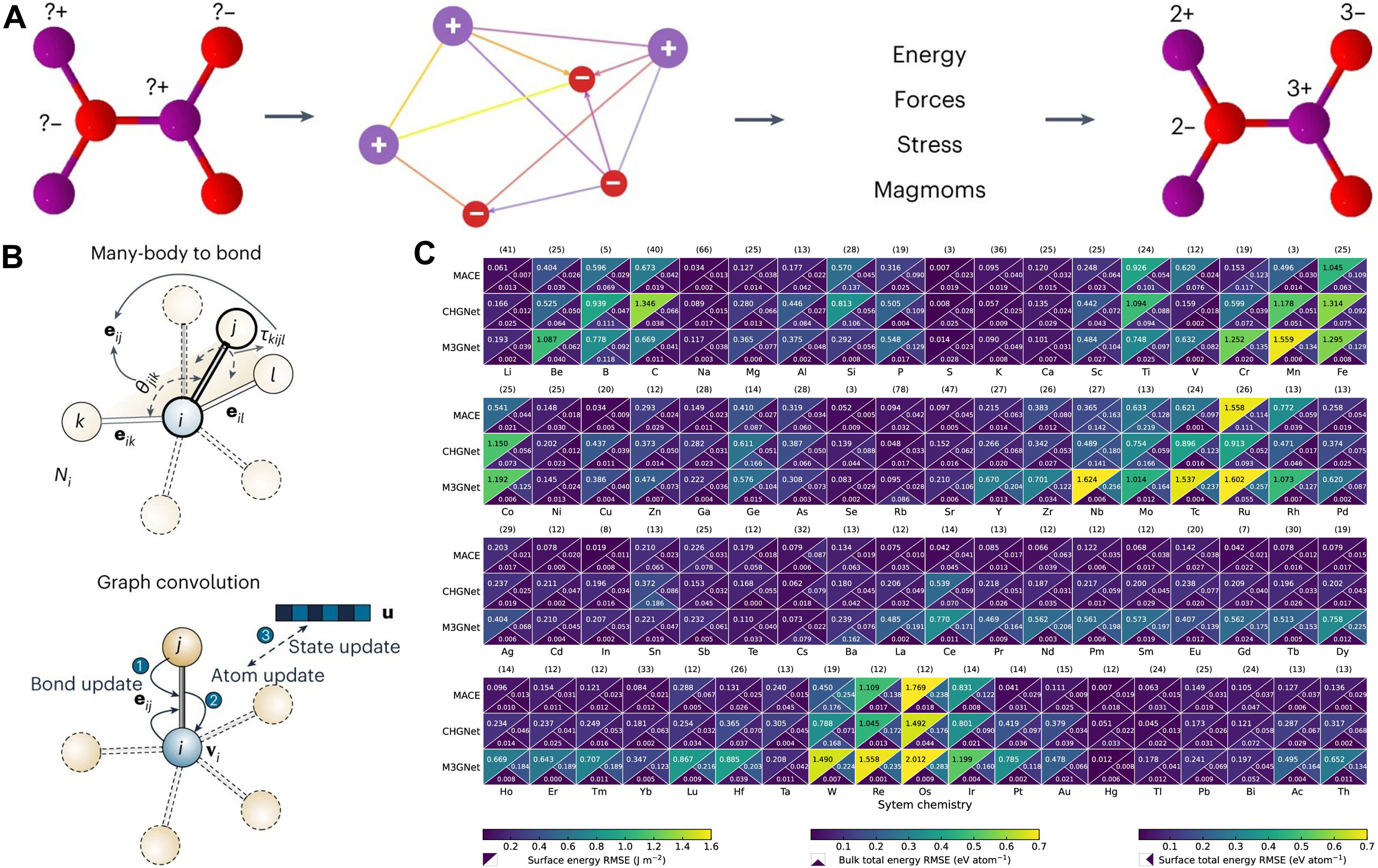

General graph-network potentials, such as Crystal Hamiltonian Graph neural Network (CHGNet)[15] and Materials 3-body Graph Network (M3GNet)[16], explicitly fuse local information - atoms, bonds, and angles - within GNNs, trading modest computational cost for robustness across diverse crystal structures and elements. CHGNet guarantees rotational invariance of scalar outputs and obtains forces by differentiating the energy; it does not enforce full E3 equivariance throughout the network. CHGNet adopts a dual-graph design: an atom graph for bond connectivity and a bond graph to capture three-body information such as bond angles [Figure 2A][15]. Despite its angular encodings, M3GNet remains an invariant-energy architecture rather than a layer-wise equivariant one. It builds upon its predecessor, MatErials Graph Network (MEGNet)[17] with explicit three-body interactions, enabling angular encoding via spherical harmonics and incorporating atomic coordinates and the cell matrix to compute stress tensors [Figure 2B][16]. In terms of efficiency, both rely on local-interaction GNNs whose computational cost scales approximately linearly with system size; the smaller architecture of the M3GNet model tends to be faster than that of CHGNet. Overall, these general-purpose potentials provide a broadly applicable, reasonably accurate starting point for simulating complex systems [Figure 2C][18].

Figure 2. (A) CHGNet (dual graph, charge-informed): a crystal is represented by an atom graph (bond connectivity) and a bond graph (three-body/angular terms), yielding predictions of energy, forces, stress, magnetic moments, and a charge-decorated structure. Adapted with permission from Deng et al.[15] (CC BY 4.0); changes made: cropped to include only panel a; (B) M3GNet (many-body-to-bond): a graph convolution architecture that builds bond features with explicit angular terms (e.g., spherical harmonic features) and uses atomic coordinates and the lattice to compute stress. Adapted with permission from Chen & Ong[16] (© Springer Nature, 2022); change made: cropped to include only the rightmost “Many-body to bond” and “Graph convolution” panels; (C) Cross model benchmark (MACE, CHGNet, M3GNet): per element heatmaps report upper triangle: surface energy RMSE (J m-2); lower left: bulk total energy RMSE (eV atom-1); lower right: surface total energy RMSE (eV atom-1); numbers in parentheses give sample counts per element; lower values are better. Adapted with permission from Focassio et al.[18] (© American Chemical Society 2024); no changes made. CHGNet: Crystal Hamiltonian Graph neural Network; CC BY 4.0: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International; M3GNet: Materials 3-body Graph Network; MACE: Message-passing Atomic Cluster Expansion; RMSE: root-mean-square error.

Symmetry-equivariant models - represented by Neural Equivariant Interatomic Potential (NequIP)[19] and Message-passing Atomic Cluster Expansion (MACE)[20] - target higher accuracy by enforcing strict E3 equivariance at every layer, ensuring that intermediate features and outputs transform correctly under rotations, reflections, and translations. NequIP introduces explicitly equivariant tensor features by embedding symmetry, which improves predictive accuracy on material properties and performs strongly with limited training data[19]. MACE combines message passing with equivariant neural networks within the Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) framework[20]. However, the high-order tensor operations increase model complexity and computational overhead, and out-of-distribution structures often require additional fine-tuning.

Extreme-efficiency models such as Orb-v3 (version 3 of the Orbital Materials interatomic potential)[21], DeePMD (Deep Potential Molecular Dynamics)[22] and Neuroevolution Potential (NEP)[23] focus on speed and scalability. To reduce complexity, Orb-v3 forgoes enforced invariance/equivariance to symmetry and strict energy conservation constraints, adopting a non-equivariant architecture that learns interatomic interactions directly. As reported, Orb-v3 can perform rapid relaxations for 105-atom systems with quasi-DFT accuracy, enabling mesoscale high-throughput simulations[21]. DeePMD replaces classical force-field models with a symmetry-preserving neural network built on local environment embeddings and molecular mechanics principles. Leveraging thousands of graphics processing units (GPUs), it supports millisecond-scale dynamics for systems with up to hundreds of millions of atoms, delivering near ab initio accuracy within the trained phase space. Although it typically requires system-specific training and a significant computational cost to achieve such accuracy[22]. NEP constructs an energy-conserving, rotation- and translation-invariant potential using compact polynomial descriptors with a small feed-forward network and trains the parameters with a separable natural evolution strategy[23]. Under the same GPU, NEP has been reported to be approximately 15 times faster than DeePMD[24].

In practice, one can begin with a general potential for coarse relaxations, then refine representative configurations using an equivariant model or DeePMD. Viewed together, the three families occupy different vertices of the applicability-accuracy-scale triangle: general potentials for rapid screening and broad applicability; equivariant models for high-accuracy potential energy surfaces on targeted systems; and efficiency-driven models to support ultra-large-scale simulations.

How MLIPs advance electrocatalysis

MLIPs have rapidly advanced, simultaneously increasing speed and reducing error while extending to a broader range of electrocatalytic materials and reactions. Shiota et al.[25] introduced MACE-Osaka24, which uses Total Energy Alignment (TEA) to merge inorganic Materials Project Trajectory (MPtrj) with organic OFF23 data (available at https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/items/d50227cd-194f-4ba4-aeb7-2643a69f025f), enabling a model to span crystals and molecules. The model predicts reaction barriers with an accuracy of 0.7 kcal/mol, maintains lattice constant errors below 1% for metal oxides, and runs 104× faster than DFT on ~105-atom systems. By delivering orders-of-magnitude lower cost than DFT, it serves as a practical engine for electrocatalysis workflows. Lim et al.[26] built a MACE DAC force field for CO2/H2O-metal-organic framework (MOF) systems by fine-tuning a high-order message-passing MACE framework, reducing the energy MAE to 0.19 eV and the force MAE to 0.10 eV Å-1. With high-order many-body representations and near-linear scaling, MACE achieves 3-4 orders of magnitude speed-ups while retaining strong generalization - well-suited for cross-material, cross-phase catalytic screening and dynamics.

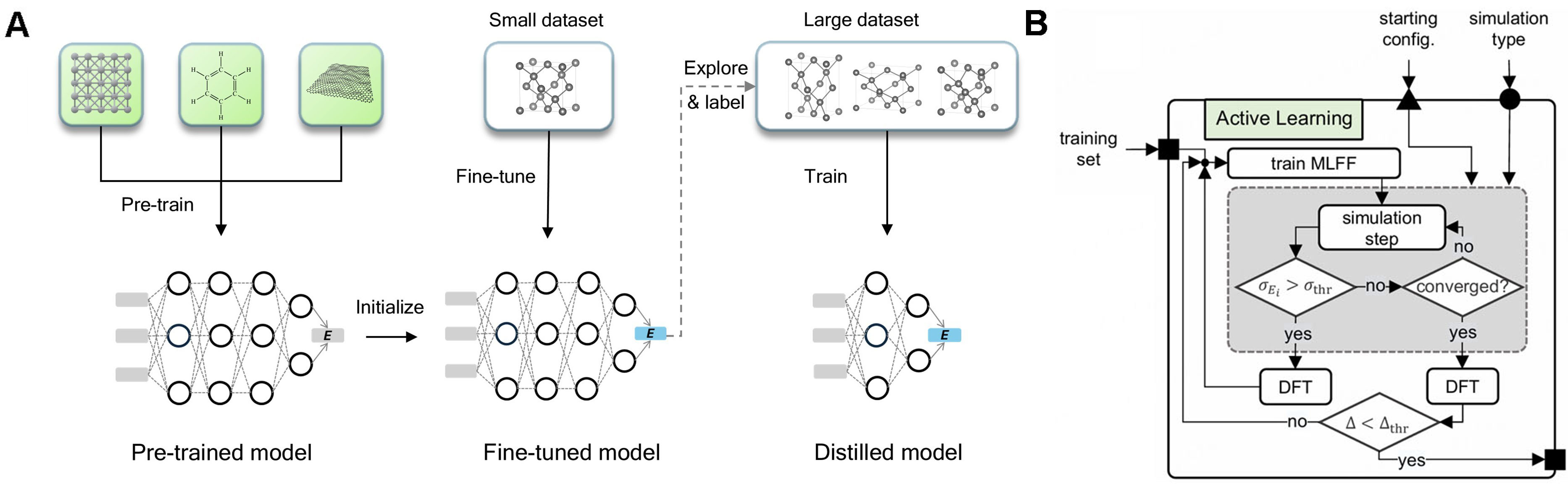

Machine learning force fields (MLFFs) are also widely used in electrocatalysis, particularly for searching transition states and pathways. With only a few hundred DFT points, several studies have reduced predictive RMSE to 0.05 eV[27] and sustained DFT-level accuracy over million-configuration energy evaluations within just a few days[28]. When broadly trained MLIPs initially show sizable errors on a specific dataset, a PFD workflow - Pre-train → Fine-tune → Distill [Figure 3A] - combined with active learning [Figure 3B] can quickly reduce errors to usable levels after adding a small amount of DFT or molecular dynamics (MD) data[29]. This strategy has proven effective in accelerating MLIPs for CO2RR and MOF-related reactive MD tasks[30,31].

Figure 3. (A) PFD workflow: fine-tune a universal pre-trained model on a small, ab initio dataset to achieve material-specific, first-principles accuracy; then distill a faster, simplified model using data generated and labeled by the fine-tuned model. Reproduced with permission from Wang et al.[29] (CC BY 4.0); no changes made; (B) Blocks iteratively sample configurations when uncertainty > σthr until Δthr is met. Adapted with permission from Schaaf et al.[27] (CC BY 4.0); changes made: cropped to only include panel b. PFD: Pre-train (P), Fine-tune (F), Distill (D); AL: active learning; MLFF: machine learning force field; DFT: density functional theory; CC BY 4.0: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

This review has surveyed recent progress in artificial intelligence (AI)-accelerated DFT for electrocatalysis. Regarding model choice, a wide range of approaches - from simple decision trees and RFs to more complex GNNs - can perform well across different catalytic systems. Researchers should weigh expressive power against the risk of overfitting, considering system complexity and available computing resources, and select solutions that ensure both computational accuracy and reliable generalizability.

For descriptors, general and easily accessible foundational descriptors are convenient and low-cost, making them suitable for initial coarse screening. Customized composite descriptors can further improve accuracy within specific systems, though many rely on DFT calculations; therefore, they are most effective for cases with relatively simple structures where rapid training and deployment are desired. In practical screening, their interpretability provides clear knobs for chemists to guide the choice of system selections and operating conditions. Beyond DFT-derived features, experimentally measurable descriptors, including onset potential, Tafel slope, Faradaic efficiency, durability metrics, and electrochemically active surface area, can be added. To ensure data consistency, standardized definitions and reporting for the reference electrode, current-resistance (iR) compensation, normalization basis, electrolyte, and pH should be used to align labels across laboratories and reduce noise[32].

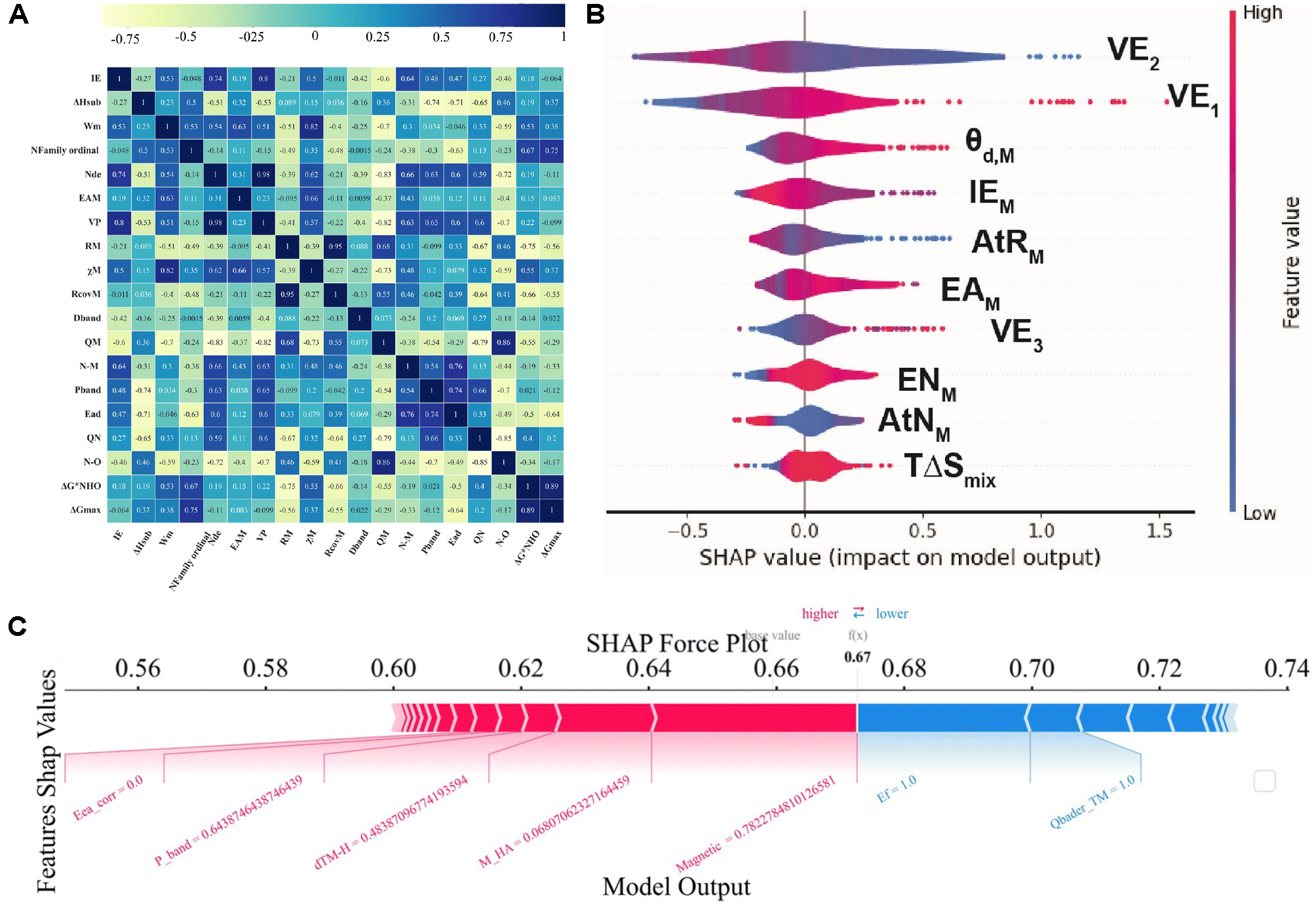

As the model ecosystem matures, a set of increasingly “off-the-shelf” MLIPs has emerged, offering moderate accuracy with fast inference and thus broad adoption. For high-dimensional descriptor tasks, principal component analysis (PCA) can be used initially to reduce dimensionality and enhance robustness[10]. Next, construct a Pearson correlation matrix to further analyze the correlations among the features [Figure 4A]. Methods such as Shapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) can then elucidate the contribution of each descriptor, thereby enhancing interpretability [Figure 4B and C][6]. To integrate experiment and theory, define a shared metadata schema that records the potential scale, electrolyte, pH, temperature, iR compensation, and the chosen normalization method. A multi-fidelity learner (e.g., a multi-output Gaussian process) can co-train on DFT labels and experimental metrics, learning cross-fidelity correlations as data arrive[33].

Figure 4. (A) Pearson correlations. Heatmap of the Pearson coefficient r among all primary features and the target. Color encodes r from -1 (strong negative; yellow) to +1 (strong positive; blue); each cell prints its r value. Adapted with permission from Zhao et al.[36] (© Royal Society of Chemistry 2024); changes made: cropped to only include panel a; (B) SHAP summary (violin) plot. X-axis: SHAP value, feature impact on the model output. Points are individual samples; violin width shows density; features are ordered by mean |SHAP|. Point color encodes the raw feature value. Positive SHAP values shift the prediction upward; negative values shift it downward. Adapted with permission from Tamtaji et al.[6] (© 2024 Elsevier.); changes made: cropped to only include panel c; (C) Local explanation and partial dependence. SHAP force plot for one example: red bars push the prediction higher relative to the model’s expected value; blue bars push it lower. Adapted with permission from Zhao et al.[10] (© Royal Society of Chemistry 2025); changes made: cropped to only include panel e. SHAP: SHapley Additive exPlanations; IE: ionization energy; ΔHsub: enthalpy of sublimation; Wm: work function of the metal; Nfamily ordinal: Family ordinal number; Nde: number of d-electrons; EAM: electron affinity of the metal; VP: valence electron number; RM: atomic radius; χM: electronegativity of the metal; RcovM: covalent radius of the metal; Dband: d-band center; QM: central atom Mulliken charge; N-M: N-metal bond length; Pband: p-band center; Ead: adsorption energy; QN: charge transferred to the N; N-O: bond length of adsorbed NO; ΔG*NHO: Gibbs free-energy change for adsorbed NHO formation; ΔGmax: maximum Gibbs free energy change; TΔSmix: T × ΔSmix (product of temperature and mixing entropy); AtNM: atomic number of the metal; ENM: electronegativity of the metal; VE3: valence electrons in 3rd ring; AtRM: atomic radius of the metal; IEM: ionization energy of the metal; θd,M: number of d electrons; VE1: valence electrons in 1st ring; VE2: valence electrons in 2nd ring; Eca_corr: corrected electron affinity; dTM-H: bond length between transition metal and hydrogen; M_HA: total heteroatom mass; Ef: formation energy; Qbader_TM: bader charge of the transition metal.

When target structures are complex and higher accuracy is required, active learning with uncertainty sampling can be introduced[27]. Starting from a general MLIP, a small amount of DFT can be used for fine-tuning to obtain a high-accuracy model tailored to the system of interest. MLIP-driven MD can replace long ab initio runs when the goal is to approach steady-state structures and thermodynamic averages. A few representative frames are then promoted to DFT for validation and short relaxations, which reduces the total number of DFT steps while preserving target accuracy. For large systems, MLIPs substantially reduce wall time at acceptable error. In practice, these models act as a triage layer in high-throughput campaigns, rapidly ranking thousands of candidates and narrowing them to synthesis-ready shortlists. Closed-loop active learning with clear stop rules can further reduce the number of expensive labels.

A practical next step is an end-to-end workflow that enables lab technicians without coding experience to easily upload data, build datasets, generate features, train models, and propose the next experiments. Such tooling would reduce DFT workload and experimental iteration, shortening the time from computation to lab validation.

Despite advances, limitations remain in AI-accelerated electrocatalysis. First, public datasets tend to focus on low-index surfaces in vacuum and relatively sparse coverages, leaving catalytically important structures underrepresented[34]. Second, the quality of labels for model training is sensitive to the choice of functional form, reference potentials, and solvent corrections. Current datasets primarily contain steady-state adsorption energies, whereas data on transition states, kinetics, and electrolyte environments are relatively scarce, which undermines model accuracy in these situations[35]. Future work should fill these data gaps, unify evaluation benchmarks, and strengthen reproducible workflows to build more comprehensive, multi-scale datasets - thereby further improving model accuracy, generality, and reproducibility.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Analyzed and interpreted the literature, prepared figures, and drafted the manuscript: Lin, Y.

Conceived the review scope, provided supervision, revised the manuscript, and guided the overall structure: Ou, P.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

The National University of Singapore supported this work through the Presidential Young Professorship (PYP) Start-Up Grant (A-0010024-00-00) and the White Space Fund (A-0010024-01-00).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

REFERENCES

1. Masa, J.; Andronescu, C.; Schuhmann, W. Electrocatalysis as the nexus for sustainable renewable energy: the gordian knot of activity, stability, and selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 15298-15312.

2. Ding, R.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Bando, Y.; Wang, X. Unlocking the potential: machine learning applications in electrocatalyst design for electrochemical hydrogen energy transformation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 11390-11461.

3. Wang, D.; Cao, R.; Hao, S.; et al. Accelerated prediction of Cu-based single-atom alloy catalysts for CO2 reduction by machine learning. Green. Energy. Environ. 2023, 8, 820-830.

4. Das, A.; Roy, D.; Manna, S.; Pathak, B. Harnessing the potential of machine learning to optimize the activity of Cu-based dual atom catalysts for CO2 reduction reaction. ACS. Mater. Lett. 2024, 6, 5316-5324.

5. Abraham, B. M.; Piqué, O.; Khan, M. A.; Viñes, F.; Illas, F.; Singh, J. K. Machine learning-driven discovery of key descriptors for CO2 activation over two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 15, 30117-30126.

6. Tamtaji, M.; Kazemeini, M.; Abdi, J. DFT and machine learning studies on a multi-functional single-atom catalyst for enhanced oxygen and hydrogen evolution as well as CO2 reduction reactions. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2024, 80, 1075-1083.

7. Chen, Z. W.; Lu, Z.; Chen, L. X.; Jiang, M.; Chen, D.; Singh, C. V. Machine-learning-accelerated discovery of single-atom catalysts based on bidirectional activation mechanism. Chem. Catal. 2021, 1, 183-195.

8. Huang, M.; Shi, R.; Liu, H.; et al. Computational single-atom catalyst database empowers the machine learning assisted design of high-performance catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2025, 129, 5043-5053.

9. Wei, C.; Shi, D.; Yang, Z.; et al. Data-driven design of double-atom catalysts with high H2 evolution activity/CO2 reduction selectivity based on simple features. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2023, 11, 18168-18178.

10. Zhao, Y.; Gao, S. S.; Ren, P. H.; Ma, L. S.; Chen, X. B. High-throughput screening and an interpretable machine learning model of single-atom hydrogen evolution catalysts with an asymmetric coordination environment constructed from heteroatom-doped graphdiyne. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2025, 13, 4186-4196.

11. Mou, L. H.; Du, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, L. Effective screening descriptors of metal-organic framework-supported single-atom catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction reactions: a computational study. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 12947-12955.

12. Lin, X.; Du, X.; Wu, S.; et al. Machine learning-assisted dual-atom sites design with interpretable descriptors unifying electrocatalytic reactions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8169.

13. Sun, H.; Liu, J. y. Advancing CO2RR with O-coordinated single-atom nanozymes: a DFT and machine learning exploration. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 14021-14030.

14. Batzner, S.; Musaelian, A.; Sun, L.; et al. E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2453.

15. Deng, B.; Zhong, P.; Jun, K.; et al. CHGNet as a pretrained universal neural network potential for charge-informed atomistic modelling. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 1031-1041.

16. Chen, C.; Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2022, 2, 718-728.

17. Chen, C.; Ye, W.; Zuo, Y.; Zheng, C.; Ong, S. P. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3564-3572.

18. Focassio, B. M. Freitas, L. P.; Schleder, G. R. Performance assessment of universal machine learning interatomic potentials: challenges and directions for materials’ surfaces. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2024, 17, 13111-13121.

19. Tan, C. W.; Descoteaux, M. L.; Kotak, M.; et al. High-performance training and inference for deep equivariant interatomic potentials. arXiv 2025, arXiv.2504.16068. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.16068 (accessed 28 October 2025).

20. Batatia, I.; Kovács, D. P.; Simm, G. N. C.; Ortner, C.; Csányi, G. MACE: higher order equivariant message passing neural networks for fast and accurate force fields. arXiv 2023, arXiv.2206.07697. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2206.07697 (accessed 28 October 2025).

21. Rhodes, B.; Vandenhaute, S.; Šimkus, V.; et al. Orb-v3: atomistic simulation at scale. arXiv 2025, arXiv.2504.06231. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.06231 (accessed 28 October 2025).

22. Zeng, J.; Zhang, D.; Peng, A.; et al. DeePMD-kit v3: a multiple-backend framework for machine learning potentials. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2025, 21, 4375-4385.

23. Fan, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, C.; et al. Neuroevolution machine learning potentials: Combining high accuracy and low cost in atomistic simulations and application to heat transport. Phys. Rev. B. 2021, 104, 104309.

24. Liu, J.; Yin, Q.; He, M.; Zhou, J. Constructing accurate machine-learned potentials and performing highly efficient atomistic simulations to predict structural and thermal properties. arXiv 2024, arXiv.2411.10911. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.10911 (accessed 28 October 2025).

25. Shiota, T.; Ishihara, K.; Do, T. M.; Mori, T.; Mizukami, W. Taming multi-domain, -fidelity data: towards foundation models for atomistic scale simulations. arXiv 2024, arXiv.2412.13088. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.13088 (accessed 28 October 2025).

26. Lim, Y.; Park, H.; Walsh, A.; Kim, J. Accelerating CO2 direct air capture screening for metal-organic frameworks with a transferable machine learning force field. Matter 2025;8:102203.

27. Schaaf, L.; Fako, E.; De, S.; Schäfer, A.; Csányi, G. Accurate energy barriers for catalytic reaction pathways: an automatic training protocol for machine learning force fields. arXiv 2023, arXiv.2301.09931. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.09931 (accessed 28 October 2025).

28. Wu, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Pan, F. Machine-learning prediction of facet-dependent CO coverage on Cu electrocatalysts. J. Mater. Inf. 2025, 5, 14.

29. Wang, R.; Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhong, Z. PFD: automatically generating machine learning force fields from universal models. arXiv 2025, arXiv.2502.20809. Available online: https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2502.20809 (accessed 28 October 2025).

30. Jiao, Z.; Mao, Y.; Lu, R.; Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, Z. Fine-tuning graph neural networks via active learning: unlocking the potential of graph neural networks trained on nonaqueous systems for aqueous CO2 reduction. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 2025, 21, 3176-3186.

31. Zheng, B.; Oliveira, F. L.; Neumann Barros Ferreira, R.; et al. Quantum informed machine-learning potentials for molecular dynamics simulations of CO2’s chemisorption and diffusion in Mg-MOF-74. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 5579-5587.

32. Voiry, D.; Chhowalla, M.; Gogotsi, Y.; et al. Best practices for reporting electrocatalytic performance of nanomaterials. ACS. Nano. 2018, 12, 9635-9638.

33. Fare, C.; Fenner, P.; Benatan, M.; Varsi, A.; Pyzer-knapp, E. O. A multi-fidelity machine learning approach to high throughput materials screening. npj. Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 257.

34. Chanussot, L.; Das, A.; Goyal, S.; et al. Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20) dataset and community challenges. ACS. Catal. 2021, 11, 6059-6072.

35. Yin, J.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; et al. CaTS: toward scalable and efficient transition state screening for catalyst discovery. ACS. Catal. 2025, 15, 15754-15764.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.