Recent advances in semiconductor quantum dots for photocatalytic CO2 reduction

Abstract

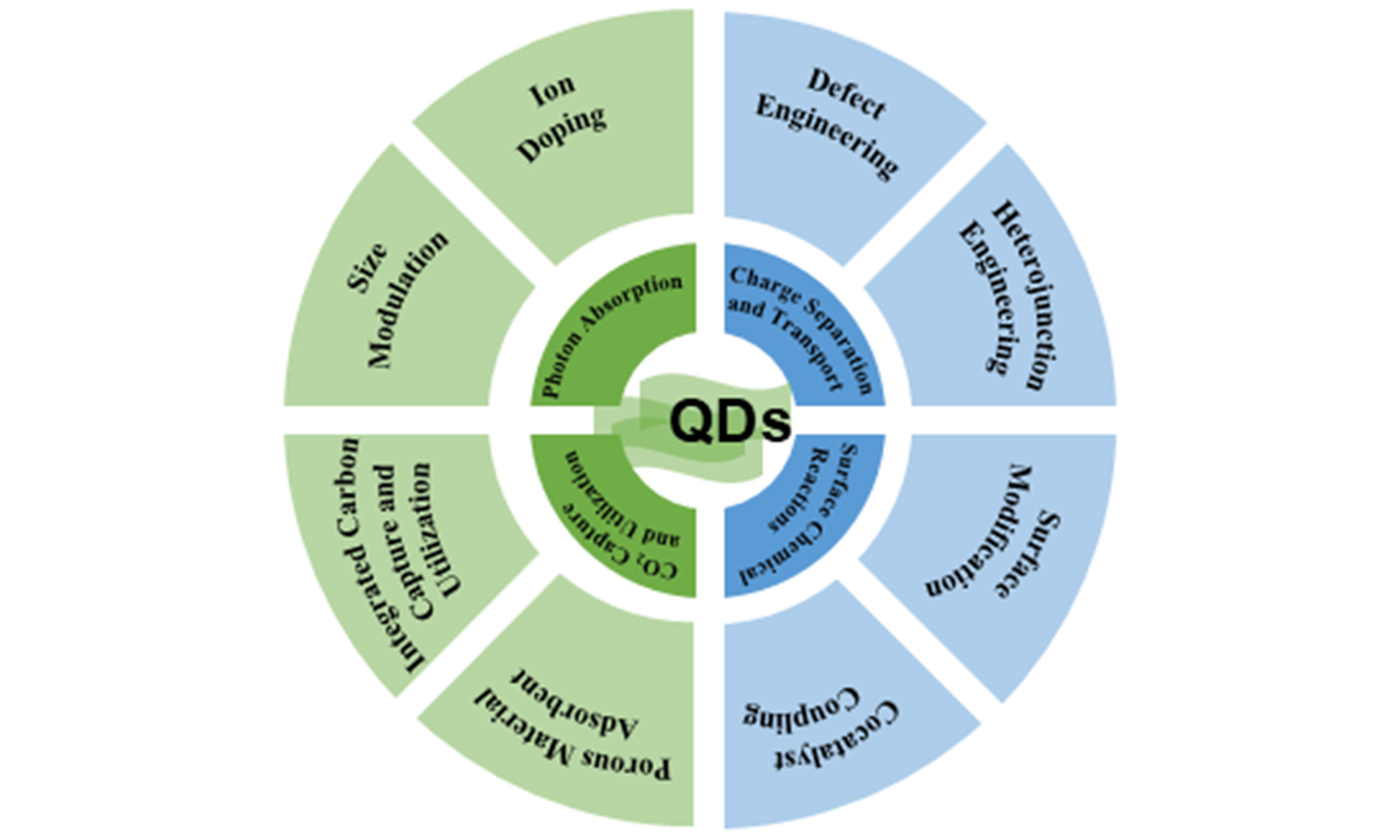

Developing efficient carbon capture, utilization and storage methods is essential to offset adverse global climate changes. Among those methods, photocatalytic CO2 conversion is emerging as an effective and sustainable solution. Among the various photocatalysts, semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) are particularly promising for the CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) due to their unique features, such as quantum confinement effect, large absorption coefficient, and beneficial surface properties. This review provides a comprehensive and distinctive perspective by integrating three critical dimensions: advanced mechanistic understanding through cutting-edge characterization techniques, systematic stability analysis under realistic operating conditions, and direct CO2 capture-utilization integration. We highlight recent strategies for improving the CO2RR performance of QDs, including bandgap tuning, ion doping, defect and heterojunction engineering, ligand modification and cocatalyst loading. We also explore integrated approaches that couple CO2 capture with photocatalytic conversion. Furthermore, we address the critical transition from laboratory demonstrations to real-world implementation by analyzing long-term stability, degradation mechanisms, and realistic cyclic operating conditions inadequately addressed in current research. Finally, we address prevailing challenges and future prospects, aiming to spark continuous innovation in applying QDs to CO2 capture and conversion.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The extensive consumption of fossil fuels over the past centuries has led to the release of substantial amounts of greenhouse gas, particularly CO2, posing a serious threat to global ecosystems and human society[1]. In response, significant efforts have been directed toward developing effective carbon capture, utilization and storage technologies to reduce atmospheric CO2 levels[2,3]. Nature provides an exemplary model in photosynthesis, which uses solar energy to convert atmospheric CO2 into value-added products, thereby storing solar energy as chemical energy[4,5]. However, natural photosynthesis is limited by low energy conversion efficiency, limited product selectivity, and its reliance on complex biological systems[6]. These limitations have spurred the development of artificial photocatalytic systems designed to overcome such challenges.

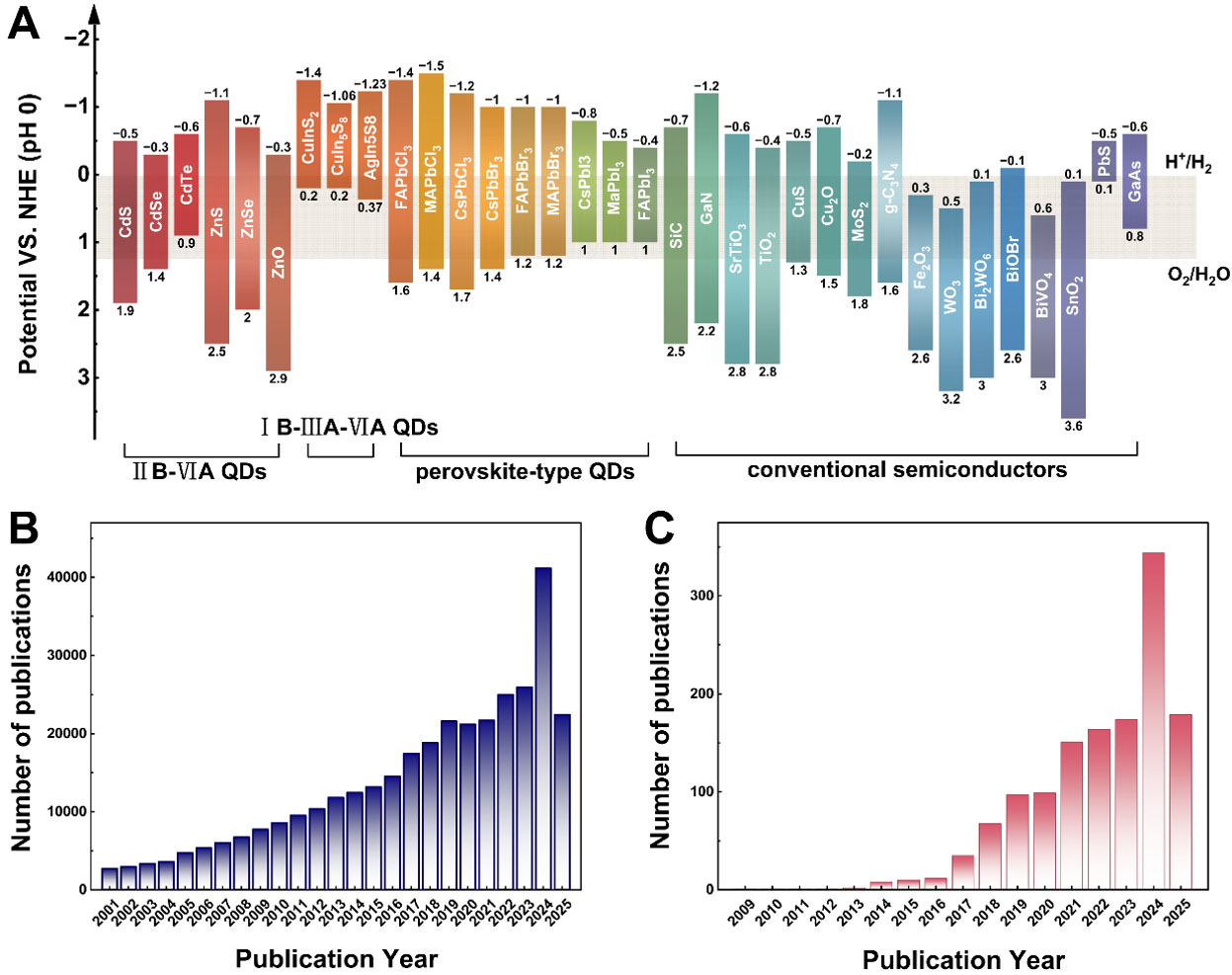

Considerable progress has been made in developing various photocatalysts for the CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR), including metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and composite structures, with some demonstrating promising conversion rates under laboratory conditions [Figure 1A][7-9]. Despite this progress, artificial photocatalysts still face significant challenges, such as insufficient visible-light absorption (as evidenced by the wide bandgaps (> 3.0 eV) of many benchmark photocatalysts that only absorb ultraviolet (UV) light), rapid charge recombination (carrier lifetimes often shorter than nanoseconds) and low solar-to-fuel conversion efficiency (< 1%). Furthermore, the inherent stability of the CO2 molecule, with a high dissociation energy of 750 kJ·mol-1 for the C=O bond, demands substantial energy input for its activation[10].

Figure 1. (A) Band energy diagrams of representative semiconductors for CO2 photoreduction (NHE: Normal Hydrogen Electrode). Number of published manuscripts categorized by the keywords of (B) Annual publication counts for “quantum dots” from 2001-2025. (C) Annual publication counts for “quantum dots” combined with “photocatalytic CO2 reduction” from 2009-2025. Data sourced from the Web of Science database.

The past decades have witnessed remarkable advances in both materials design and mechanistic understanding of photocatalytic CO2 reduction[11]. Among the diverse range of photocatalysts, semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) have emerged as particularly promising candidates. Defined by their nanoscale dimensions (typically 1-10 nm, smaller than the Bohr exciton radius), QDs exhibit unique optoelectronic properties that distinguish them from their bulk counterparts and molecular catalysts[12-14]. These advantageous characteristics include: (1) High Absorption Coefficients: QDs typically possess high molar extinction coefficients, enabling highly efficient harvesting of photon energy. For example, the molar extinction coefficient of CsPbX3 (where X is a halogen ion) is approximately 105-107 L·mol-1·cm-1[15];

Common QD families include binary compounds from groups II-VI (e.g., CdS, CdSe, ZnO)[18-20], ternary I-III-VI compounds (e.g., CuInS2, CuAlS2)[21-23], and a new generation of perovskite-type QDs (e.g., CsPbBr3, CH3NH3PbBr3, Cs2AgBiBr6) renowned for their exceptional optoelectronic properties[24-26]. In this review, we focus on the application of semiconductor QDs in photocatalytic CO2RR and the direct coupling of CO2 capture with its utilization. We begin by summarizing the fundamental thermodynamics and kinetics of photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Subsequently, we discuss key strategies for enhancing the performance of QD photocatalysts, including bandgap engineering, heterostructure design, and surface modification to improve light absorption, charge separation, and surface reaction kinetics. Distinctively, we provide an in-depth examination of cutting-edge characterization techniques that enable real-time monitoring of reaction intermediates, active site evolution and photocatalyst stability, addressing a critical knowledge gap in mechanistic understanding. We also present comprehensive analysis of integrated CO2 capture and utilization (CCU) approaches using QD-metal-organic framework (MOF) and QD-covalent organic framework (COF) composites, evaluating both technical feasibility and realistic energy balance considerations. We also examine integrated approaches for direct CO2 CCU, addressing associated challenges and potential solutions. Finally, we present a perspective on the remaining challenges and future directions in this vibrant field, particularly emphasizing the transition from laboratory demonstrations to practical implementation through realistic stability testing and energy-efficient system design, aiming to provide a roadmap for developing high-performance QD-based systems for sustainable carbon management.

LIGHT-DRIVEN CO2 REDUCTION REACTION

Principles of CO2 reduction

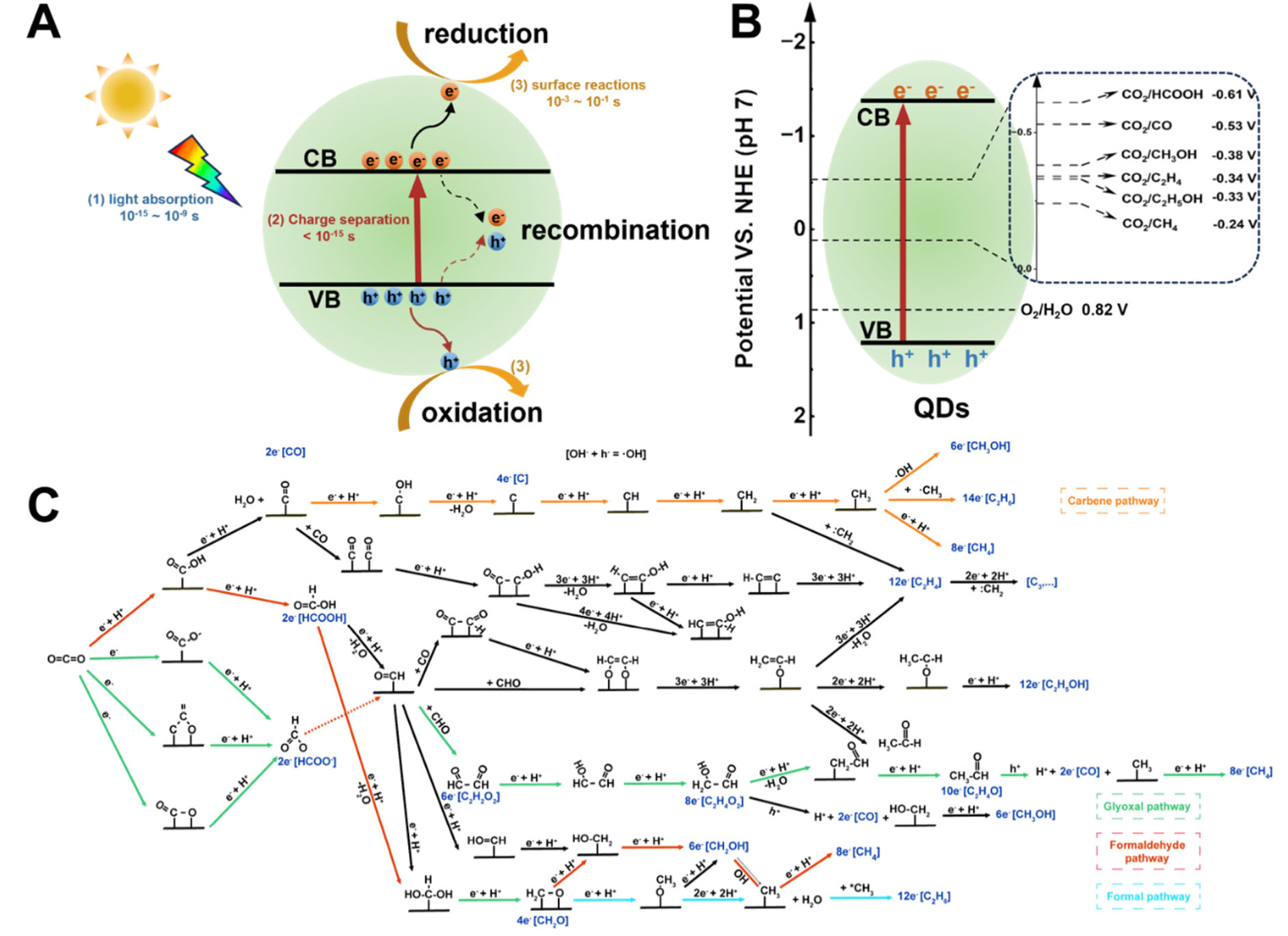

As shown in Figure 2A, the photocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) generally involves three sequential steps that occur within a time frame of 10-15 to 10-1 seconds[27-29]: (i) Light Absorption (10-15-10-9 s): A photocatalyst absorbs photons with energy exceeding its bandgap, exciting electrons from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) to generate electron-hole (e-/h+) pairs; (ii) Charge Separation and Migration (< 10-15 s): the photogenerated charge carriers separate and migrate from the bulk phase to the active sites on the surface of the photocatalyst; (iii) Surface Redox Reactions (10-3-10-1 s): Adsorbed CO2 molecules are reduced by electrons, while holes oxidize water or sacrificing agents. And efficient CO2RR demands both suitable semiconductor band alignment and effective charge utilization. Thermodynamically, the CB minimum must be more negative than the CO2 reduction potentials, while the VB maximum must be more positive than the oxidation potential of the electron donor. Kinetically, rapid charge transfer to surface active sites is critical to outcompete the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, which occurs on picosecond to millisecond timescales.

Figure 2. Schematic of the photocatalytic CO2 reduction mechanism. (A) Key steps in the photocatalytic process on a semiconductor quantum dot (QD), with characteristic timescales for each step; (B) Redox potentials versus NHE for CO2 reduction to various products at pH 7; (C) Proposed reaction pathways and intermediates for the formation of different CO2 reduction products[11]. Adapted with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society.

The photocatalytic CO2RR is inherently challenging. Chemically, the CO2 molecule is linear and thermodynamically stable, with a high C=O bond dissociation energy of 750 kJ·mol-1, making it difficult to activate[30]. Physically, its low aqueous solubility (0.033 mol·L-1 at 25 °C and 1 atm[31]) limits mass transfer to the catalyst surface in aqueous environments. Despite these challenges, the CO2RR proceeds through several key steps. The process initiates with the adsorption of a CO2 molecule onto the photocatalyst surface. This is followed by a kinetically slow, one-electron reduction to form a bent *CO2 radical anion, a step that requires a substantial energy input (ca. -1.9 V vs. NHE (Normal Hydrogen Electrode)), as given in

Subsequent proton-coupled electron transfer steps then occur, leading to the breakage of O=C=O bonds and the formation of key intermediates such as dentate (*OCHO) or carboxyl (*COOH) species. These intermediates are ultimately converted into various products such as CO, CH4, HCOOH, and CH3OH through divergent reaction pathways [Figure 2B], as given in

A representative network of these potential photocatalytic synthesis pathways is summarized in

Evaluation metrics for photocatalytic CO2RR performance

The performance of a photocatalytic CO2RR in a particulate suspension system is typically quantified using six metrics[35]: (1) CO2 conversion rate; (2) production rate; (3) selectivity; (4) turnover number (TON) or turnover frequency (TOF); (5) quantum efficiency and (6) solar-to-chemical (STC) conversion efficiency. The CO2 conversion rate is defined as the ratio of reacted CO2 to the initial CO2 feedstock, as given in

This, though often omitted, is crucial for evaluating the total consumption of CO2 across all products[36]. It depends not only on the catalyst’s intrinsic activity but also on reaction conditions such as time and total amount of CO2 supplied[37]. Production rate refers to the yield of a specific product (e.g., CO, CH4, HCOOH) per unit time and per mass of catalyst, as determined by

This is the most commonly reported metric for evaluating performance in heterogeneous photocatalytic systems. In addition, when multiple products are formed during the photocatalytic process, the selectivity metric is used to measure the tendency of formation of the target product over all products, as calculated using

Unlike other metrics, a key consideration in this calculation is the inclusion of H2 production, a common competing side reaction. For a homogenous system with a clearly defined active site, TON and TOF are used to quantify catalytic efficiency, defined as the number of product molecules generated per active site over a reaction period (TON) or per unit time (TOF), as given by

While straightforward for homogeneous catalysts with well-defined active sites, accurately determining the number of active sites poses a significant challenge in heterogeneous systems. Quantum efficiency is an important metric to measure the effectiveness of a photocatalyst in converting incident photons into chemical energy. Generally, the apparent quantum efficiency (AQE), which is based on the total incident photon flux, is widely used due to its practical measurability[38], as given in

Calculating AQE requires knowing the number of electrons needed to form a given product (e.g., 2 for CO or HCOOH, 8 for CH4). Finally, STC conversion efficiency evaluates the overall efficiency of converting the full spectrum of solar energy into chemical energy stored in the products, as given by

This is the most comprehensive metric for assessing practical solar fuel generation, though it is currently reported in only a limited number of studies[39].

Beyond these qualitative metrics, a comprehensive assessment of a catalyst’s overall performance must also include its stability and recyclability. The challenge of distinguishing between different degradation mechanisms in QD photocatalysts requires a coordinated characterization approach that correlates temporal performance changes with microscopic structural evolution[40]. For instance, operando X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) can differentiate between active site poisoning (evidenced by surface oxidation state changes) and bulk structural degradation (revealed through coordination environment analysis)[41]. When coupled with time-resolved photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy, these techniques help distinguish whether performance loss originates from increased surface trap states (photo-corrosion) or altered charge separation dynamics (interface degradation in heterostructured QDs)[42]. Ion migration pathways, particularly critical in perovskite QDs, can be tracked through secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) depth profiling combined with in-situ electrical measurements[43]. The temporal correlation between halide redistribution (detected by SIMS) and photocurrent decay patterns helps identify whether performance degradation stems from compositional instability or morphological changes.

To distinguish dominant degradation pathways, a systematic approach is often applied to correlate degradation kinetics with environmental conditions[44]. Rapid performance loss under illumination (hours) typically indicates photochemical degradation, while gradual decline over weeks suggests ion migration or chemical poisoning[45]. For example, comparing stability under dry CO2 versus humid CO2 environments can isolate moisture-induced degradation from CO2-specific effects, while reversibility tests (thermal annealing or chemical treatment) distinguish between permanent structural changes and recoverable surface poisoning.

Furthermore, optimizing photocatalytic systems requires balancing these metrics, as enhancing one often comes at the expense of another[35]. For instance, while increasing light intensity can enhance production rates, CO2 conversion, and TON/TOF, it typically reduces both quantum efficiency and STC conversion efficiency due to heightened charge recombination losses. Beyond technical performance metrics, techno-economic analysis (TEA) is crucial for evaluating the commercial viability of photocatalytic CO2RR systems[46]. Key economic parameters, including the cost of catalyst production, capital expenditure (CAPEX), and operating expenses (OPEX), are fundamentally determined by the technical performance metrics achieved under solar irradiation[47-49]. Furthermore, the inherent intermittency of sunlight and the costs associated with large-scale photoreactor installations present unique economic challenges for photocatalytic CO2RR systems[50-52]. Therefore, optimizing technical metrics such as performance under low-light conditions and long-term catalyst durability is not merely a scientific goal but an economic imperative to minimize the levelized cost of solar fuel production.

ADVANCES IN QD-BASED PHOTOCATALYTIC CO2 CONVERSION SYSTEMS

As stated, photocatalytic CO2 reduction generally includes three essential steps: light absorption, charge separation/migration and surface redox reactions. Furthermore, given the low concentration of CO2, the efficient capture and adsorption of CO2 molecules on the catalyst surface are critical prerequisites for high performance. This section details recent advances in enhancing the overall efficiency of QD-based photocatalytic CO2RR. We will examine key strategies focused on: Broadening and intensifying light absorption, suppressing charge carrier recombination, and facilitating CO2 adsorption and activation at active sites [Table 1].

Various parameters associated with CO2RR catalyzed by QDs

| Photocatalyst | Surface loading | Reactant | Sacrificial agent | Gas species | Gas evolution rate | Light source | Reactionduration | Efficiency | Ref. |

| CsPbBr3 | None | Gas-solid phase reaction | CO/CH4 | 75.50/4.02 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 5 h | AQE = 4.47% (420 nm) | [56] | |

| CdS | Cu | water | CO/CH4 | 30.3/5.90 μmol·g-1·h-1 | Λ > 400 nm, 100 mW·cm-2 | 8 h | AQE = 0.03% (420 nm) | [57] | |

| CuInS2 | Co | water | CO | 15.24 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | [58] | |||

| CdS | Ni | CO/CH4 | 9.38/1.83 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 12 h | [59] | |||

| Cu 0.05Zn2.95In2S6 | CQDs | water/acetonitrile | TEOA | CO | 70.69 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | [60] | ||

| CdSe | g-C3N4 | water | CH4 | 47 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 5 h | [61] | ||

| CdS | Cu | acetonitrile | CO/H2 | 0.12/0.21 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 6 h | [62] | ||

| ZnIn2S4 | BP | KCO3 | H2/CO | 15.0/27.2 μmol | 300 W Xe lamp | 4 h | [63] | ||

| CuInS2 | Zn | water | ascorbic acid | CO | 535.3 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 380 < λ < 780 nm, 100 mW cm-2 | 120 h | AQY = 0.32% (400 nm) | [64] |

| g-C3N4 | CQDs | water vapor | CO/CH4 | 79.2/2.7 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | AQY = 0.02% (420 nm) | [65] | ||

| CsPbBr3 | Bi2WO6 | EA/water | CO | 251.5 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 2 h | [68] | ||

| CsPbBr3 | TiO2 | acetonitrile/water | BIH | CO | 9.02 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 4 h | [69] | |

| g-C3N4 | BiVO4 | water | CO/CH4 | 5.19/4.57 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 6 h | [70] | ||

| g-C3N4 | CQDs | CO/CH4 | 5.88/2.92 μmol·g-1·h-1 | AQE = 0.076% | [71] | ||||

| CuInS2 | TiO2 | water vapor | CH4/CH3OH | 2.5/0.86 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 350 W Xe lamp | 3 h | [72] | ||

| CdSe | CdS | water | CO/H2 | 495/401.25 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 8 h | [73] | ||

| CsPbBr3 | TiO2 | ethyl acetate/water | CO | 145.28 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 4 h | QE = 0.126% (420 nm) | [75] | |

| CsPbBr3 | ZnO | water | TEOA | CO | 85.55 μmol·g-1·h-1 | Xe lamp | 4 h | [76] | |

| Cs3Bi2Br9 | SnO2 | acetonitrile/water | CH4 | 1.78 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 12 h | [77] | ||

| Bi | CsPbBr3 QDs | water vapor | CO/CH4 | 31.55/43.11 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 5 h | [78] | ||

| CsPbBr3 | ferrocene carboxylic acid (FCA) ligand | water vapor | CO/C2H4 | 132.8/1.6 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 5 h | QE = 0.072% | [82] | |

| CsPbBr3 | Ni(tpy) | water | CO/CH4 | 1724 μmol·g-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 4 h | [83] | ||

| CsPbBr3 | Ru | CO2 | CO | 28.12 μmol·g-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 6 h | [85 | ||

| CdSe | Carbonic | 20 mM NaHCO3 | TEA | CO | 47.3 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 4 h | [86]] | |

| CdS QDs/NC | Co(bpy)32+ (bpy = 2,2′bipyridine) a | acetonitrile/water | CO | 5120 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 5 h | [87] | ||

| CdSe | PEI-LA | water | TEOA | CO | 4.98 mmol g-1 | blue LED lamp (λmax = 450 nm) | 6 h | [88] | |

| CsPbBr3 | MOF | water vapor | CH4 | 29.63 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 100 W Xe lamp | 3 h | EQE = 0.035% (386 nm) | [89] | |

| Cs2AgBiBr6 | Ce-UiO-66-H | water | CO | 309.01 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 2 h | [91] | ||

| Cs3Bi2Br9 | Bi-MOF | water | CO/CH4 | 572.24/35.502 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 2 h | [92] | ||

| CsPbBr3 | COF | water | CO/CH4 | 5.15/1.713 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 8 h | [95] | ||

| CdS/BN | Ti3C2 | water | CO/CH4 | 1.45/0.44 μmol·g-1·h-1 | 300 W Xe lamp | 5 h | [96] |

Strategies to enhance light absorption

Absorbing photon energy to generate charge carriers is the initial step of the photocatalytic CO2RR process[53]. The visible spectrum (400-800 nm) encompasses approximately 50% of solar emission energy. Thus, the performance of QD-based photocatalysts depends critically on extending their absorption edge into this region and maximizing their absorption efficiency. This section reviews key strategies for enhancing the light-harvesting capabilities of QDs, including ion doping[54], size modulation[55], localized surface plasmonic resonance effect[56], and others.

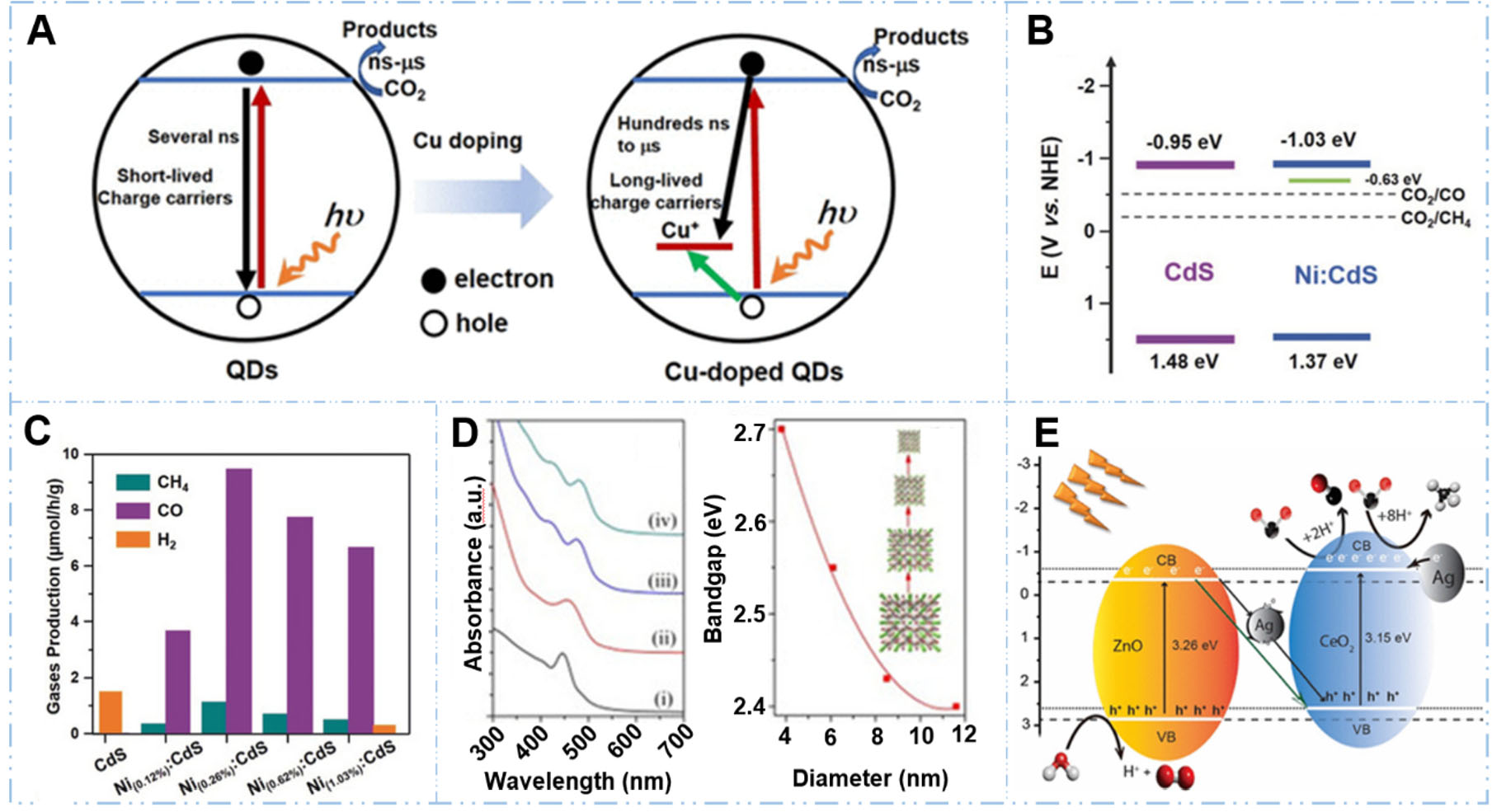

Introducing foreign atoms into the host lattice of QDs is a powerful method to tailor their physicochemical and photoelectronic properties. Doping could be categorized into three different primary types: metal doping (e.g., with transition metals such as Cu[57], Co[58], Ni[59]), non-metal doping (e.g., with N[60], P[61], S, C), and co-doping (simultaneous introduction of different elements). These doping methods enable precise modulation of the host's energy level, creating intermediate states that extend the photon absorption of the QDs into the visible light region, thereby enhancing light utilization. Among these approaches, metal atom doping leverages the introduction of d-orbital states to alter the host's energy levels, enabling tailored electronic properties. For example, Zhang et al. synthesized Cu-doped CdS QDs through a hot-injection method followed by cation exchange, where Cu dopants were introduced into the CdS lattice at varying nominal Cu/Cd molar ratios (0.125% to 2%)[57]. The Cu doping introduced intermediate energy levels within the bandgap that enabled sub-bandgap photon absorption, thus extending the light absorption spectrum into the visible region [Figure 3A]. Compared to the pristine CdS QDs, the PL emission intensity of Cu:CdS QDs exhibited a considerable enhancement (~40 times) higher than that of the pristine CdS QDs. Photocatalytic evaluation revealed that under visible-light irradiation, the optimally Cu:CdS QDs exhibited CO and CH4 production rates of 30.3 and 5.9 μmol·g-1·h-1, respectively, whereas pristine CdS showed negligible activity[57]. Also, Gao et al.[62] introduced Cu doping into CdS QDs (Cu:CdS QDs) at varying concentrations (0.125% to 0.184%) via a one-pot method. Distinguished from prior studies on Cu:CdS, this study employs a Cu-doping strategy that serves a dual purpose: enhancing light harvesting and promoting charge separation via Cu-induced electron enrichment. The incorporated copper also acts as an active site for CO2 adsorption and activation. This dual contribution significantly improves visible-light utilization and promotes syngas formation with a tunable CO/H2 ratio. Under visible light illumination (λ > 420 nm), the optimal Cu:CdS QDs (0.036% molar ratio Cu of CdS) achieved synergistic photocatalytic performance with 96.4% benzylamine conversion and tunable syngas production (CO/H2 ratios from 2:1 to 1:2), where CO and H2 yields reached 7.20 and 12.34 μmol after 6 h while simultaneously producing 31.54 μmol of dibenzyl amine with > 99% selectivity. In addition to Cu, other metals have similar properties: Yang et al.[58] synthesized Co-doped CuInS2 (Co/CuInS2) nanoflowers via an oil-bath method followed by high-temperature calcination. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) analysis revealed that Co doping did not significantly alter the absorption in the UV and near-infrared regions but notably enhanced it across the visible spectrum. Further data and electrochemical measurements indicated a shift in band positions and a narrowing of the bandgap from 1.52 to 1.41 eV, which corroborates the observed enhancement in visible-light absorption. Consequently, under 300 W Xenon (Xe) lamp irradiation, the Co/CuInS2 catalyst achieved a CO production rate of

Figure 3. Strategies for enhancing the light absorption of QDs. (A) Cu doping in CdS QDs extends the light absorption range and improves charge separation[57]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[57]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (B and C) Ni doping increases the light utilization efficiency of CdS QDs[59]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[59]. Copyright 2018, John Wiley and Sons; (D) Size-dependent tuning of the absorption spectrum in CsPbBr3 QDs[55]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[55]. Copyright 2017, John Wiley and Sons; (E) Enhanced absorption in a CeO2-ZnO QD system through the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect of Ag nanoparticles[56]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[56]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

While metal doping can enhance light absorption through bandgap engineering, non-metal doping offers a complementary strategy by primarily modifying the VB structure. For instance, Yang et al.[60] synthesized nitrogen-doped carbon QDs (NCQDs) from corn straw biomass using tryptophan as the nitrogen source to achieve high pyridine-nitrogen content (17.56%), which were then used to modify Cu0.05Zn2.95In2S6 photocatalysts (CZIS@CQDs-T). The NCQD modification enhanced light harvesting efficiency to over 70% and improved photon conversion in the 370-410 nm region through up-conversion of low-energy photons to high-energy photons. The optimized CZIS@CQDs-T photocatalyst, under a 300 W Xe lamp irradiation, achieved a CO production rate of 70.69 μmol·g-1·h-1 with nearly 100% selectivity, representing a 4.77-fold enhancement over the unmodified material. Also, Raziq et al.[61] developed CdSe QDs coupled with phosphorus-doped graphitic carbon nitride (CdSe/P-CN) nanocomposites through a facile thermal treatment and wet chemical approach, where phosphorus atoms substituted carbon sites in the graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) lattice. Phosphorus doping significantly narrowed the bandgap from 2.7 eV (pristine g-C3N4) to 2.2 eV (P-CN), while coupling with CdSe QDs extended the visible-light absorption range from 450 to 700 nm. Under a

Furthermore, the light absorption characteristics of QDs can be precisely tuned via the quantum confinement effect by controlling their physical dimensions. For instance, Hou et al.[55] systematically tuned the bandgap of perovskite CsPbBr3 QDs by varying their size from 3 to 12 nm [Figure 3D]. The optimized QDs with a diameter of 8.5 nm exhibited exceptional photocatalytic performance under 300 W Xe lamp irradiation, achieving > 99% selectivity for CO2 reduction to CO and CH4 and an electron consumption yield of 20.9 μmol·g-1·h-1. Beyond quantum size effects, localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) offers a powerful alternative mechanism to enhance light absorption. In plasmonic QDs, the collective oscillations of free charge carriers at the metal-semiconductor interface generate intense localized electromagnetic fields, dramatically amplifying photon absorption, particularly in noble metal-decorated QD systems. For example, Mahyoub et al.[56] synthesized Ag-CeO2-ZnO (AgCZ) through hydrothermal and photo-deposition methods, where Ag nanoparticles (NPs, 3 wt% optimal loading) were uniformly dispersed on the CeO2-ZnO composite surface [Figure 3E]. The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of Ag NPs dramatically extended light absorption from the UV region into the visible spectrum. The optimized 3AgCZ photocatalyst achieved exceptional CO2 reduction performance with CH4 production rate of 302 μmol·g-1·h-1 and 89.3% selectivity under simulated sunlight. In summary, these strategies, when combined with appropriate heterostructure engineering and morphological design synergistically, have proven highly effective for enhancing the light-harvesting capability of QDs in photocatalytic CO2 reduction.

Strategies to improve charge separation

To achieve high quantum efficiency for QD-photocatalyzed CO2 reduction, it is crucial to separate electrons from holes and facilitate their migration to surface active sites for subsequent reactions[14]. A significant challenge arises from the fact that charge carrier lifetimes in QDs typically range from picoseconds to nanoseconds [Figure 2A], a timescale comparable to that of recombination. Researchers have developed various ways to drive effective charge transfer in QDs through heterojunction construction[63], defect engineering[64], etc.

Heterojunction construction is to combine two or more semiconductors through hydrothermal, in-situ growth or other synthesis methods[65]. Based on the arrangement of the components’ energy band structures, photocatalyst heterojunctions can be classified as type I (straddling), type II (staggered), type III (broken-gap), Z-scheme, and S-scheme heterojunctions[66,67]. This section will detail the application of three typical heterostructures: type II, Z-scheme, and S-scheme heterojunctions in enhancing charge transfer for photocatalytic CO2 reduction.

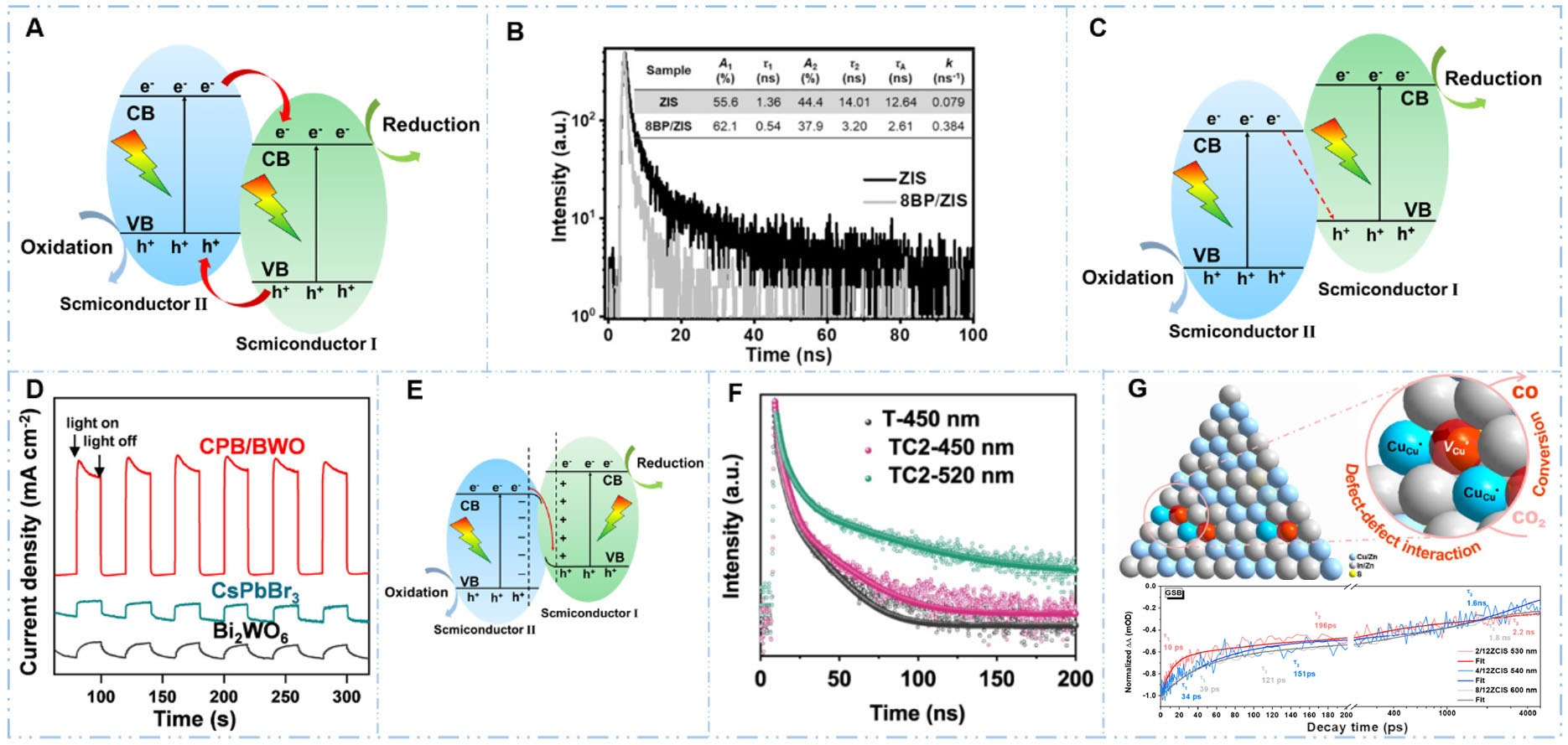

Type II heterojunctions are formed between two semiconductors with a staggered band alignment

Figure 4. Strategies for enhancing charge separation and transfer in QDs. (A) A schematic representation of type II heterojunction; (B) Transient absorption spectra demonstrating improved charge separation by forming type II heterojunction[63]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[63]. Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons; (C) A schematic representation of Z-scheme heterojunction; (D) Photocurrent response (I-t curve) showing enhanced photocurrent by Z-scheme heterojunction engineering[68]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[68]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society; (E) A schematic representation of S-scheme heterojunction; (F) Transient absorption spectra confirming prolonged carrier lifetime by constructing S-scheme heterojunction[69]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[69]. Copyright 2020, Xu et al.[69]; (G) Cu defect engineering improved charge separation in CuInS QDs, as evidenced by transient absorption spectroscopy[64]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[64]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

While type II heterojunctions are effective in promoting the separation of photogenerated charge carriers, thermodynamic analysis reveals that they will decrease the overall redox abilities of photocatalysts[70]. An alternative strategy, inspired by natural photosynthesis [Figure 4C][71,72], is the Z-scheme heterojunction, which achieves the desired charge separation without compromising redox ability. In this configuration, photogenerated electrons in the CB of one semiconductor recombine with holes in the VB of the other semiconductor (via conductive mediators or direct interfacial contact). This strategic recombination selectively removes charge carriers with weaker redox potential, thereby preserving the most potent electrons and holes in their original components, resulting a system that achieves spatial charge separation while maintaining strong driving forces for both reduction and oxidation reactions. For instance, Wang et al.[68] synthesized a direct Z-scheme heterojunction by growing 0D CsPbBr3 (CPB) QDs on 2D Bi2WO6 (BWO) nanosheets through an in-situ growth strategy for visible-light-driven CO2 photoreduction. The band positions of Bi2WO6 and CsPbBr3, determined by UV-Vis DRS and VB XPS tests, reveal a favorable band alignment between the two semiconductors, which is suitable for the formation of a Z-scheme heterojunction. This heterojunction formation significantly enhanced charge-carrier separation and transfer efficiency, as evidenced by PL quenching and a robust photocurrent response [Figure 4D]. The optimized CPB/BWO composite achieved a product yield of 503 μmol·g-1 under visible-light illumination (λ > 400 nm), representing a 9.5-fold enhancement over pristine CsPbBr3 QDs. In another example, Zhang et al. engineered hybrid CdSe/CdS QDs with Z-scheme band alignment heterostructure through an oil bath method, creating a cooperative photoredox system that simultaneously reduced CO2 while selectively oxidizing thiol[73]. The heterostructure formation established an internal electric field (IEF) at the CdSe/CdS interface that significantly enhanced photoinduced charge carrier separation and transfer efficiency, as confirmed by PL quenching, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and transient photocurrent measurements. The optimized CdSe/CdS QDs achieved simultaneous production of tunable syngas

The S-scheme heterojunctions are comprised of two closely bound photocatalysts, an oxidation photocatalyst (OP) and a reduction photocatalyst (RP), and the RP possesses higher CB, VB, and Fermi level than the OP [Figure 4E][74]. Before light irradiation, Fermi level equilibration generates an IEF at the RP/OP interface, pointing from RP to OP. This causes the CB and VB of RP to bend upward, while the CB and VB of OP bend downward. As a result, photogenerated electrons from the CB of OP can recombine with holes in the VB of RP, and electrons in the CB of RP and holes in the VB of OP are driven from the interior toward the

While heterojunction engineering effectively enhances charge separation through interfacial electric fields and band alignment optimization, the intrinsic electronic structure of individual semiconductor components also plays a critical role in the charge separation process. Defect engineering, by intentionally introducing structural deficiencies (e.g., oxygen or metal vacancies), can modify band structures and provide additional charge trapping or detrapping sites, suppressing charge recombination, to enhance photocatalytic performance[80,81]. For instance, Cai et al.[64] synthesized Cu-deficient CuInS2 QDs (ZCIS QDs) by precisely controlling the Cu/In ratio to manipulate copper defect states [Figure 4G]. Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy confirmed that this defect engineering significantly enhanced charge carrier dynamics. The optimally deficient QDs (2/12ZCIS with Cu/In ratio of 2/12) achieved a high photocatalytic activity for CO2 reduction to CO with a rate of 400-500 μmol·g-1·h-1, which was 24-fold enhancement compared to the stoichiometric 8/12ZCIS QDs. In summary, both heterojunction construction (Type II, Z-scheme, S-scheme) and intrinsic defect engineering are powerful strategies for suppressing electron-hole recombination. By ensuring that a greater number of photoexcited carriers reach the catalyst surface, these methods are fundamental to driving efficient CO2 activation and reduction.

Strategies to improve surface chemical reactions

The ultimate determinant of photocatalytic efficiency and product selectivity lies in the surface-mediated processes that occur after charge carriers arrive. These processes, including CO2 adsorption, activation, and multi-electron and proton transfer, are governed by the local chemical environment, the atomic configuration of active sites, and the ability to stabilize key reaction intermediates. Consequently, significant research efforts are dedicated to engineering the QD surface to enhance these critical steps. This section reviews prominent strategies, such as surface ligand modification[82] and cocatalyst loading[83], which are designed to optimize surface reaction kinetics and steer product distribution.

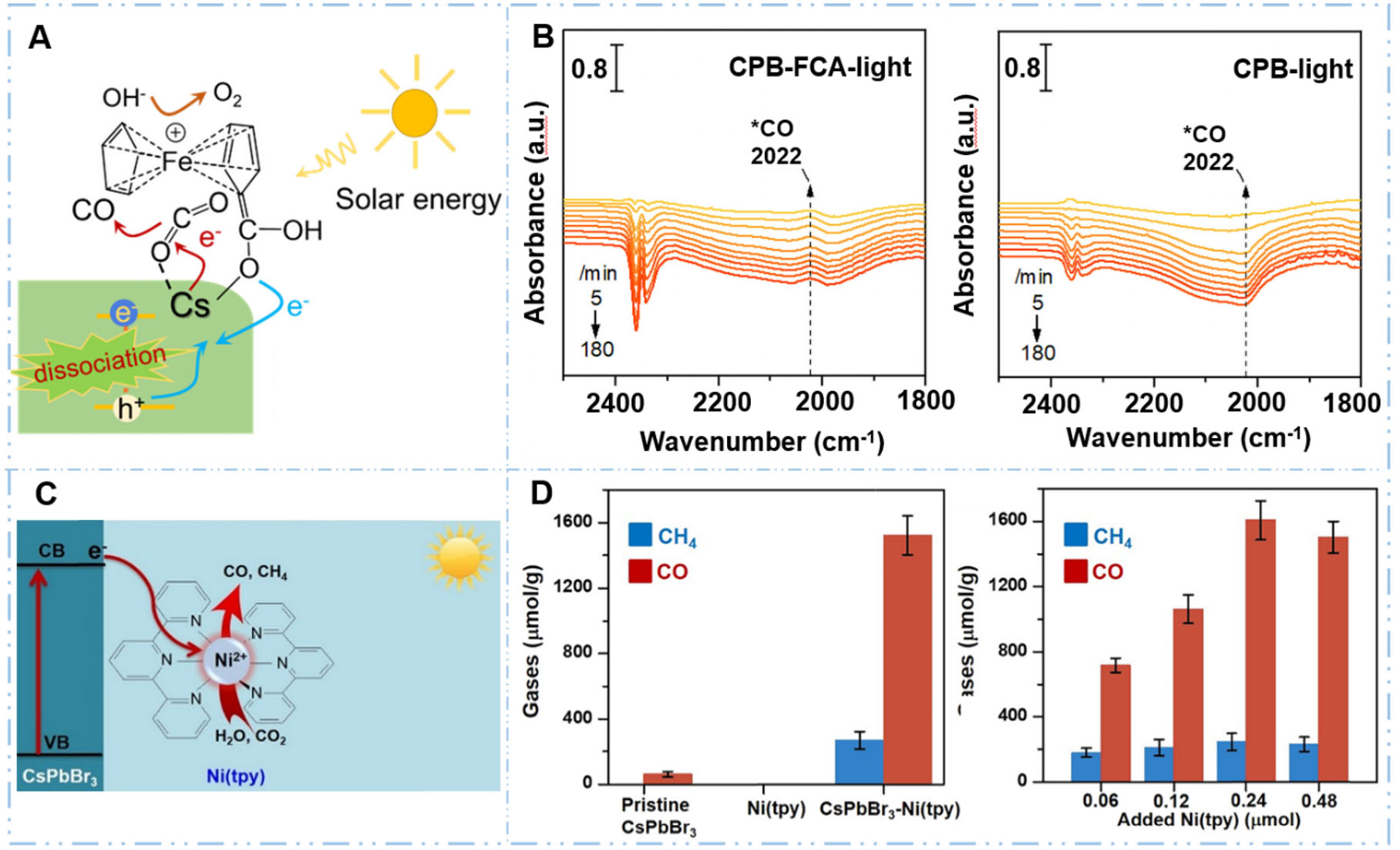

Among these approaches, surface modification directly tailors the chemical and electronic properties of the QD surface where catalysis occurs. By introducing specific ligands, functional groups, or dopants, these modifications can modulate CO2 binding affinity, alter surface charge, and create specific active sites that facilitate electron transfer to adsorbed reactants. For example, Du et al.[82] modified CsPbBr3 QDs with ferrocene carboxylic acid (FCA) ligands that grafted onto the QD surface through Cs atom coordination [Figure 5A]. The FCA ligands significantly enhanced CO2 adsorption and activation, reducing the adsorption energy to -2.5256 eV (approximately half that of pristine QDs). The sandwich structure of ferrocene created natural CO2 capture sites, and in situ Diffuse reflectance infrared fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements combined with Density functional theory (DFT) calculations confirmed that these strengthened CO2-surface interactions and favorable binding configurations facilitate subsequent electron transfer to the activated CO2 molecules [Figure 5B]. The activity test showed that the FCA-modified CsPbBr3 exhibited an impressive CO2 to CO conversion rate of 132.8 μmol·g-1·h-1 under the 300 W Xe lamp irradiation, which is approximately ninefold higher than that of pristine CsPbBr3 QDs. Furthermore, surface engineering can stabilize key reactive intermediates through coordination interactions and steric effects, thereby lowering activation barriers and directing product selectivity toward desired reduction pathways. For instance, Sahm et al.[84] functionalized ZnSe QDs with imidazolium-terminated thiol ligands (MEMI) that not only passivated surface Zn sites to suppress competing hydrogen evolution but also created a favorable secondary coordination sphere for CO2 reduction. The positively-charged imidazolium ligands stabilized the key *CO2δ- radical intermediate through π-p orbital interactions and hydrogen bonding, lowering the activation barrier for the rate-determining electron transfer step (0.77 eV) and enhancing CO production by 4-fold and selectivity by 13-fold compared to pristine ZnSe QDs under the UV-filtered simulated solar light (λ > 400 nm).

Figure 5. Strategies enhancing surface reaction kinetics in QDs. (A and B) Surface reaction kinetics of CsPbBr3 QDs were improved through surface ligand modifications of ferrocene carboxylic acid[82]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[82]. Copyright 2024, National Academy of Sciences; (C and D) The surface reaction kinetics of CsPbBr3 QDs were improved through loading Ni(tpy) molecular catalyst as cocatalyst[83]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[83]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

Surface modification focuses on optimizing the intrinsic active sites of QDs through chemical engineering, while cocatalyst loading aims to introduce external active centers with distinct catalytic functionalities. These cocatalysts, typically metals[85], metal oxides or molecular complexes[83], provide additional reaction sites and can spatially separate oxidation and reduction processes, thereby enabling tandem catalytic pathways. For example, Yu et al. decorated CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs with dispersed Ru NPs (~1.5 nm) as cocatalysts, which served as active centers for CO2 reduction and significantly enhanced CO production to 28.12 μmol·g-1·h-1 under simulated visible-light irradiation[85]. This activity is approximately fourfold and 1.6-fold higher than that of CsPbBr3 QDs and Ru NPs, respectively. The Ru NPs provided highly active sites with superior CO2 adsorption capacity (-1.516 eV) and dramatically lowered the activation energy barrier for forming the rate-limiting *COOH intermediate from 1.23 to 0.68 eV, thereby accelerating the surface catalytic kinetics as evidenced by DFT calculations and in situ Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, validating the mechanism by which the metal cocatalyst optimizes the CO2 reduction pathway. Also, Chen et al.[83] immobilized cationic Ni(terpyridine) metal complexes onto CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs through electrostatic interactions with surface PF6- anions, creating spatially separated catalytic centers for CO2 reduction

Capture and conversion of CO2 molecules

Although strategic optimizations of photon absorption, charge separation, and surface reactions have substantially improved the performance of photocatalytic CO2 reduction in laboratory settings, its translation to real-world scenarios is hampered by a critical issue: the substrate concentration problem[86]. Most laboratory studies employ pure CO2 or saturated CO2 streams to maximize conversion rates, yet real-world CO2 sources, whether atmospheric air at 420 ppm or industrial flue gas at 4%-15%, present severely diluted, multicomponent streams. At these low concentrations, mass transfer limitations, unfavorable thermodynamics, and competitive adsorption (especially from H2O) severely reduce photocatalytic efficiency. This situation has spurred the development of integrated carbon CCU systems. These systems aim to synergistically combine selective CO2 capture with photocatalytic conversion in tandem configurations, enabling these processes to work synergistically rather than sequentially. To facilitate CO2 concentration and adsorption, researchers are incorporating QDs with various high-affinity capture materials, such as porous carbon-based materials[87], amine-based materials[88], MOFs[89-92], COFs[93-96], enzymes[86], and others[97], to create hybrid architectures that enhance overall CCU efficiency.

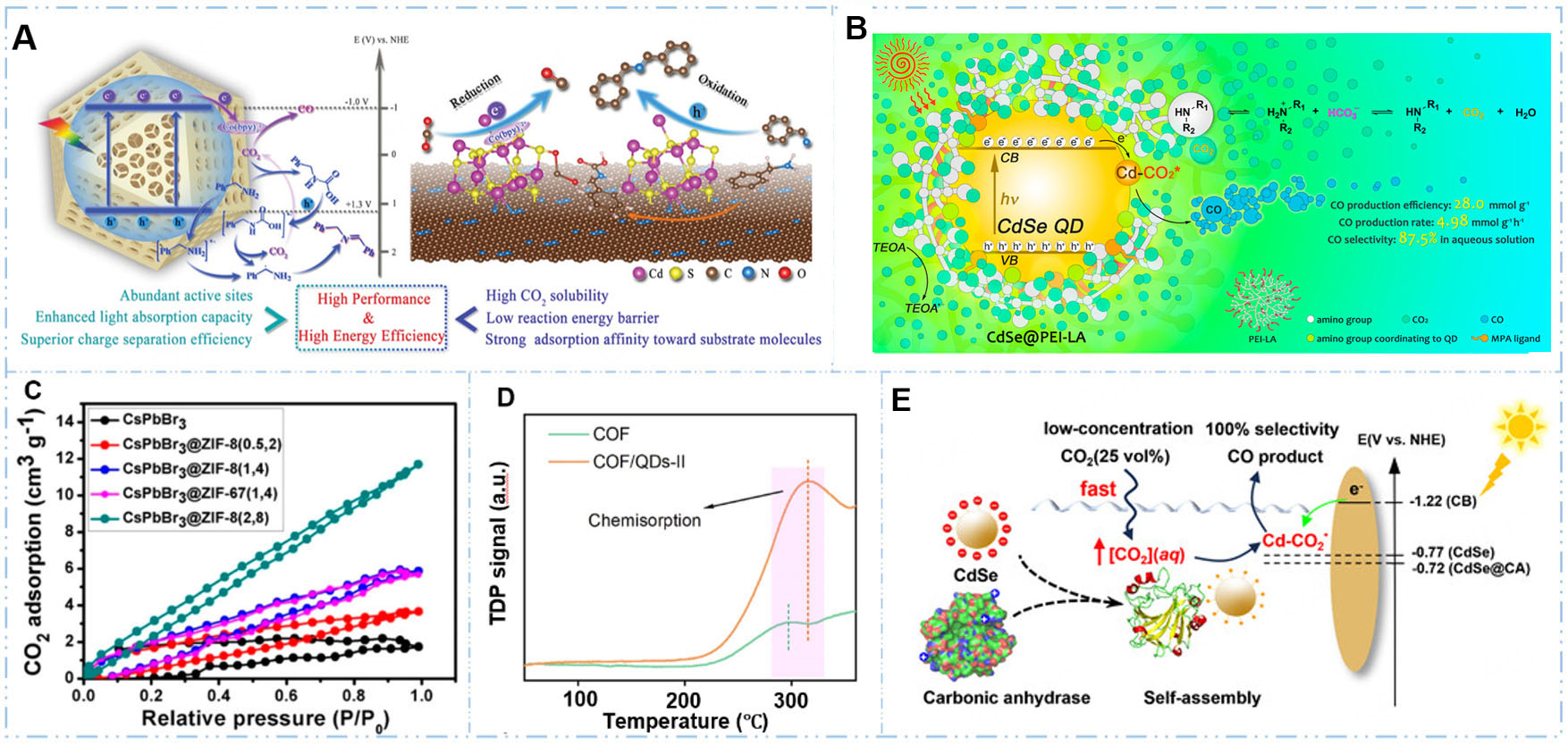

Porous carbons combine high surface area, tunable pore structure, strong and selective CO2 adsorption, facile regeneration, and excellent stability, establishing them as versatile and cost-effective platforms for carbon capture technologies. Wang et al.[87] synthesized CdS QDs supported on 3D ordered macroporous N-doped carbon (3DOM CdS QD/NC) through an in situ transformation strategy [Figure 6A]. Under visible light irradiation, the resulting photocatalyst achieved an exceptional CO production rate of 5,210 μmol·g-1·h-1 using benzylamine oxidation as the coupled oxidation reaction and maintained 34% activity

Figure 6. Strategies to integrate CO2 capture with utilization (CCU). (A) Integration of QDs with porous carbon-based materials[87]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[87]. Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons; (B) Integration of QDs with amine-based polymers[88]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[88]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society; (C) Integration of QDs with MOFs[89]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[89]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society; (D) Integration of QDs with COFs[95]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[95]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society; (E) Integration of QDs with carbonic anhydrase enzyme[86]. Reproduced with permission from ref.[86]. Copyright 2025, John Wiley and Sons.

Amine-functionalized porous polymers, ranging from linear polyethylenimine to porous organic frameworks with primary, secondary, or tertiary amine functionalities, enable integrated CCU platforms by selectively capturing CO2 from dilute gas mixtures through strong amine-CO2 interactions while simultaneously serving as solid supports for QDs, thereby creating bifunctional materials that concentrate and convert CO2 within a single architecture. Wu et al.[88] encapsulate CdSe QDs in an amphiphilic polymer (polyethylenimine-lauric acid (PEI-LA)) through electrostatic interactions and surface coordination to form CdSe@PEI-LA assemblies [Figure 6B]. The resulting system achieved a CO production efficiency of 28.0 mmol·g-1 with 87.5% selectivity under visible light irradiation, representing 57-fold and 1.5-fold enhancements, respectively, compared to pristine CdSe QDs. The PEI-LA polymer addresses CO2 capture through multiple mechanisms as evidenced by CO2 solubility measurements showing 66.7% increased CO2 dissolution in water at optimized PEI-LA concentration and FTIR spectroscopy confirming reversible chemisorption through carbamate formation between amino groups and CO2.

In CCU systems, MOFs function as both CO2 adsorbents and support matrices for QDs, where post-synthetic modification or in situ synthesis strategies incorporate QDs into MOF pores or surfaces to create bifunctional materials that capture dilute CO2 from ambient or industrial sources, concentrate it within the porous network near photocatalytic QD sites, and enable photocatalytic conversion under mild conditions. Kong et al.[89] synthesized core@shell nanocomposites by in situ coating zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8 or ZIF-67) shells onto CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs through direct growth. The as-synthesized photocatalysts achieved electron consumption rates of 15.5 and 29.6 μmol·g-1·h-1 for CsPbBr3@ZIF-8 and CsPbBr3@ZIF-67, respectively, representing 1.39-fold and 2.66-fold improvements over pristine CsPbBr3. The ZIF shells provide enhanced CO2 absorption capacity through the microporous framework structure to create high local concentrations near photocatalytic sites in integrated CCU systems with capacity reaching 5.93 cm3·g-1, which was a 3.68-fold increase compared to QDs alone [Figure 6C]. In addition, Ding et al. synthesized a bifunctional composite by in situ embedding lead-free double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 QDs into C48H24Ce6O32 (Ce-UiO-66-H) MOF through solvothermal growth[91]. The optimized 20% Cs2AgBiBr6 QDs loading on the Ce-UiO-66-H (20CABB/UiO-66) composite achieved a CO production rate of

While MOFs provide effective platforms for integrating CO2 capture and photocatalytic conversion with QDs, the emerging class of COFs offers an alternative strategy featuring metal-free, fully covalent architectures with tunable porosity and nitrogen-rich functional groups that can enhance CO2 chemisorption. For instance, He et al.[95] synthesized Triphenylamine (TPA)-COF/CsPbBr3 QD hybrid materials by electrostatic self-assembly. The optimized COF/QDs-II composite achieved CO and CH4 production rates of 41.2 and 13.7 μmol·g-1, respectively, over 8 h under a 300 W Xe arc lamp without any cocatalyst or scavenger, representing substantial improvements over bare COF and QDs. The reasons could be attributed to the enhanced CO2 chemisorption of COF/QDs, as evidence by desorption peaks shifting to higher temperatures compared to pristine COF [Figure 6D], indicating stronger CO2-catalyst interactions, and DFT calculations quantified that QD surfaces provide more negative adsorption energies (-0.41 eV) than COF (-0.16 to

Natural photosynthesis utilizes light and atmospheric CO2 to synthesize carbohydrates for sustaining life on Earth[98]. During the dark reaction, various enzymes[99,100] were involved in the process to concentrate CO2 for subsequent reactions. Carbonic anhydrase (CA), as one of the most active enzymes, could catalyze the quick interconversion between aqueous form CO2 and HCO3- (k = 106 s-1), thus facilitating CO2 concentration process[101-103]. For example, our research group[86] designed and synthesized a self-assembled biohybrid system consisting of CdSe QDs with CA. At 100% CO2 concentration, this system achieved a CO2 conversion rate of 47.3 μmol·g-1·h-1, which was 3.5-fold higher than the bare CdSe QDs. Even under simulated flue gas conditions (15% CO2), the CdSe@CA system still maintained a CO2 conversion rate of 8.2 μmol·g-1·h-1

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

In conclusion, QDs have emerged as powerful photocatalysts for CO2 reduction, with significant progress achieved through systematic engineering. Key advancements include the expansion of light-harvesting capabilities via doping, size/composition control, and plasmonic enhancement; the suppression of charge recombination through sophisticated heterostructures (Type-II, Z-scheme, S-scheme); and the optimization of surface reactions using tailored ligands and cocatalysts to improve selectivity and kinetics. A critical recent realization is that high performance under pure CO2 conditions does not translate to real-world applications, where dilute sources such as air (~420 ppm) or flue gas (4%-15%) impose severe mass-transfer limitations. This has spurred the development of integrated CCU systems, where QDs are combined with adsorbents such as MOFs, COFs, or enzymes to concurrently concentrate and convert CO2, bridging a vital gap between laboratory research and practical deployment.

Despite this promising trajectory, several formidable challenges must be addressed to realize the commercial viability of QD-based photocatalytic CO2 reduction:

(1) Low quantum efficiency and economic viability: Solar-to-fuel conversion efficiencies typically remain below <1%, far from the ~10% threshold for economic competitiveness. Breakthroughs are needed to mitigate thermalization losses, enhance infrared photon utilization, improve charge separation, and lower the high overpotentials of multi-electron reactions.

(2) Competition from hydrogen evolution: The HER is a major selectivity challenge due to its overlapping potential with CO2 reduction. The goal is to realize a universal efficiency of ≥90% for CO2 reduction products. Suppressing HER requires precise engineering of surface sites, the local pH environment, and CO2 concentration at the catalyst interface.

(3) Limited product value: Current systems predominantly yield low-value two-electron products, CO and HCOOH, rather than more commercially valuable multi-electron products such as CH4, CH3OH, or C2+ hydrocarbons. Steering selectivity toward more valuable multi-carbon products (e.g., CH4, CH3OH, C2+) necessitates overcoming significant kinetic barriers for C-C coupling and deep reduction through precise control of proton-coupled electron transfer and intermediate stabilization.

(4) Oxidation half-reaction limitations: Coupled with the CO2 reduction reaction, the oxidation half-reaction, typically water oxidation to O2 or sacrificial agent decomposition, suffers from sluggish kinetics due to the four-electron/four-proton transfer process or results in wasting photogenerated holes and generating undesirable byproducts. Consequently, identifying alternative oxidation reactions that can utilize these holes to produce value-added chemicals, such as selective organic oxidations (benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde) or biomass upgrading reactions, has emerged as a critical research priority for developing economically viable and sustainable photocatalytic CO2 conversion systems.

(5) Challenges in carbon capture integration: While bifunctional materials combining CO2 adsorption and photocatalytic conversion show promise in laboratory demonstrations, significant challenges remain in integrating these processes at scale, including regeneration energy requirements for adsorbents, heat management during exothermic adsorption, and maintaining photocatalytic activity in the presence of impurities from real flue gas streams. Beyond the technical hurdles, a critical gap exists in realistic energy balance assessment. Current research predominantly reports photocatalytic conversion efficiencies under isolated conditions, failing to account for the substantial energy overhead of complete adsorption-conversion-regeneration cycles, including cooling for enhanced CO2 capture, illumination for conversion, and thermal regeneration. Future work must prioritize calculating net energy ratios (NER) - the energy content of produced fuels divided by total cycle energy input - with comprehensive techno-economic analyses that account for carbon abatement costs alongside product value.

The development of dynamic systems that can cycle between capture and conversion modes without performance degradation, while operating under realistic temperature and pressure conditions, represents a major engineering hurdle for practical CCU deployment. Particularly given the insufficient attention to long-term cyclic stability under realistic operating conditions, most studies examine < 10 idealized cycles, while practical deployment requires stable operation over thousands of cycles with multiple degradation pathways including thermal stress from temperature cycling, chemical poisoning from real flue gas contaminants (SOx, NOx, particulates), and photochemical degradation from prolonged UV exposure. Future research must adopt standardized testing protocols that better reflect industrial conditions, including extended cycling with realistic cycle times, real flue gas compositions rather than pure CO2, and continuous monitoring of both capture capacity and photocatalytic activity throughout operation.

(1) Environmental and toxicity concerns: Many high-performance QDs (e.g., CdSe, CsPbBr3) contain toxic heavy metals. The development of environmentally benign, high-efficiency alternatives, such as heavy metal-free perovskites (e.g., Cs3Bi2Br9) and organic semiconductors, represents a critical direction for sustainable photocatalytic technologies, though these alternatives often suffer from reduced charge mobility and photostability compared to their counterparts. The development of non-toxic QDs (free of Cd, Pb, etc.) must meet two key criteria: compliance with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure (EPA TCLP) standard for leaching toxicity, and a benchmarked AQE reaching > 70% of that achieved by heavy-metal-based control samples.

(2) Long-term stability: Operational instability due to moisture, active site poisoning, ion migration pathways, surface reconstruction, photodegradation products photocorrosion and ion migration, particularly in perovskite QDs, remains a critical barrier. Achieving thousands of hours of stable operation requires advanced encapsulation and passivation strategies that do not compromise catalytic activity or charge transfer.

Despite these multifaceted challenges, QDs-based photocatalytic CO2 reduction, particularly when integrated with carbon capture technologies, represents a highly promising pathway for sustainable carbon management. Overcoming these hurdles through interdisciplinary collaboration will be essential to transform innovative laboratory demonstrations into scalable, economically viable technologies capable of mitigating global climate change.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote the first version of the manuscript: Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.

Contributed to the revision of the manuscript: Wu, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Hong, J.; Song, N.; He, J.; Guo, Z.; Liang, M.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 2244077), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFA1205801), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. T2225026, 82172087, 82071308, and 52202344), and the Beijing Institute of Technology Research Fund Program for Young Scholars.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

REFERENCES

1. Gambhir, A.; George, M.; Mcjeon, H.; et al. Near-term transition and longer-term physical climate risks of greenhouse gas emissions pathways. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 12, 88-96.

2. Stolarczyk, J. K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Polavarapu, L.; Feldmann, J. Challenges and prospects in solar water splitting and CO2 reduction with inorganic and hybrid nanostructures. ACS. Catal. 2018, 8, 3602-35.

3. Wu, H. L.; Li, X. B.; Tung, C. H.; Wu, L. Z. Semiconductor quantum dots: an emerging candidate for CO2 photoreduction. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1900709.

4. Barry, B. A.; Brahmachari, U.; Guo, Z. Tracking reactive water and hydrogen-bonding networks in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1937-45.

5. Guo, Z.; He, J.; Barry, B. A. Calcium, conformational selection, and redox-active tyrosine YZ in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving cluster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018, 115, 5658-63.

6. Proppe, A. H.; Li, Y. C.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; et al. Bioinspiration in light harvesting and catalysis. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 828-46.

7. Tang, J.; Guo, C.; Wang, T.; et al. A review of g‐C3N4‐based photocatalytic materials for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Carbon. Neutralizat. 2024, 3, 557-83.

8. Murali, G.; Reddy Modigunta, J. K.; Park, Y. H.; et al. A review on MXene synthesis, stability, and photocatalytic applications. ACS. Nano. 2022, 16, 13370-429.

9. Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, L.; Qi, J.; Xing, C. Biological hybrid systems based on photocatalysts to drive the conversion of CO2 into high-value compounds. ACS. Appl. Bio. Mater. 2025, 8, 2735-50.

10. Kang, H.; Ma, J.; Perathoner, S.; Chu, W.; Centi, G.; Liu, Y. Understanding the complexity in bridging thermal and electrocatalytic methanation of CO2. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 3627-62.

11. Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Insight into the selectivity-determining step of various photocatalytic CO2 reduction products by inorganic semiconductors. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 10760-88.

12. Karthikeyan, C.; Arunachalam, P.; Ramachandran, K.; Al-mayouf, A. M.; Karuppuchamy, S. Recent advances in semiconductor metal oxides with enhanced methods for solar photocatalytic applications. J. Alloys. Compd. 2020, 828, 154281.

13. Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z. Rational design of metal halide perovskite nanocrystals for photocatalytic CO2 Reduction: recent advances, challenges, and prospects. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2022, 7, 2043-59.

14. Sun, P.; Xing, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhou, W. Recent advances in quantum dots photocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 458, 141399.

15. Ravi, V. K.; Markad, G. B.; Nag, A. Band edge energies and excitonic transition probabilities of colloidal CsPbX3(X = Cl, Br, I) perovskite nanocrystals. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2016, 1, 665-71.

16. Zhu, S.; Xiao, F. Transition metal chalcogenides quantum dots: emerging building blocks toward solar-to-hydrogen conversion. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 7269-309.

17. Park, Y. H.; Murali, G.; Modigunta, J. K. R.; In, I.; In, S. I. Recent advances in quantum dots for photocatalytic CO2 reduction: a mini-review. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 734108.

18. Xiang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J.; Macyk, W. Cadmium chalcogenide (CdS, CdSe, CdTe) quantum dots for solar-to-fuel conversion. Adv. Phontonic. Res. 2022, 3, 2200065.

19. Ahmed, A. T.; Altalbawy, F. M.; Al-Hetty, H. R. A. K.; et al. Cadmium selenide quantum dots in photo- and electrocatalysis: advances in hydrogen, oxygen, and CO2 reactions. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2025, 199, 109831.

20. Yao, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Advances in green colloidal synthesis of metal selenide and telluride quantum dots. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 277-84.

21. Gui, R.; Jin, H.; Wang, Z.; Tan, L. Recent advances in synthetic methods and applications of colloidal silver chalcogenide quantum dots. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 296, 91-124.

22. Torimoto, T.; Kameyama, T.; Uematsu, T.; Kuwabata, S. Controlling optical properties and electronic energy structure of I-III-VI semiconductor quantum dots for improving their photofunctions. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C. 2023, 54, 100569.

23. Chen, S.; Zu, B.; Wu, L. Optical applications of CuInSe2 colloidal quantum dots. ACS. Omega. 2024, 9, 43288-301.

24. Sheng, J.; He, Y.; Huang, M.; Yuan, C.; Wang, S.; Dong, F. Frustrated lewis pair sites boosting CO2 photoreduction on Cs2CuBr4 perovskite quantum dots. ACS. Catal. 2022, 12, 2915-26.

25. Chen, Z.; Huang, N.; Xu, Q. Metal halide perovskite materials in photocatalysis: design strategies and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 481, 215031.

26. Chen, S.; Yin, H.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Stabilization and performance enhancement strategies for halide perovskite photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2203836.

27. Jing, L.; Xu, Y.; Xie, M.; et al. Cyano-rich g-C3N4 in photochemistry: design, applications, and prospects. Small 2024, 20, e2304404.

28. Lu, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Q.; et al. Recent advances in novel materials for photocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction. Carbon. Neutralizat. 2024, 3, 142-68.

29. Hu, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, S.; et al. Identifying a highly efficient molecular photocatalytic CO2 reduction system via descriptor-based high-throughput screening. Nat. Catal. 2025, 8, 126-36.

30. Mao, J.; Li, K.; Peng, T. Recent advances in the photocatalytic CO2 reduction over semiconductors. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 2481.

31. Diamond, L. W.; Akinfiev, N. N. Solubility of CO2 in water from -1.5 to 100 °C and from 0.1 to 100 MPa: evaluation of literature data and thermodynamic modelling. Fluid. Phase. Equilib. 2003, 208, 265-90.

32. Shafaat, H. S.; Yang, J. Y. Uniting biological and chemical strategies for selective CO2 reduction. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 928-33.

33. Wang, Y.; Chen, E.; Tang, J. Insight on reaction pathways of photocatalytic CO2 conversion. ACS. Catal. 2022, 12, 7300-16.

34. Wang, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, C. Developments and challenges on enhancement of photocatalytic CO2 reduction through photocatalysis. Carbon. Resour. Convers. 2024, 7, 100263.

35. Fang, S.; Rahaman, M.; Bharti, J.; et al. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Nat. Rev. Methods. Primers. 2023, 3, 61.

36. Ma, Y.; Yi, X.; Wang, S.; et al. Selective photocatalytic CO2 reduction in aerobic environment by microporous Pd-porphyrin-based polymers coated hollow TiO2. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1400.

37. Cao, Y.; Guo, L.; Dan, M.; et al. Modulating electron density of vacancy site by single Au atom for effective CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1675.

38. Wu, Y. A.; Mcnulty, I.; Liu, C.; et al. Facet-dependent active sites of a single Cu2O particle photocatalyst for CO2 reduction to methanol. Nat. Energy. 2019, 4, 957-68.

39. Yu, H.; Chen, F.; Li, X.; et al. Synergy of ferroelectric polarization and oxygen vacancy to promote CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4594.

40. Fu, C.; Wan, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. Artificial CO2 photoreduction: a review of photocatalyst design and product selectivity regulation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 28618-57.

41. Barawi, M.; Mesa, C. A.; Collado, L.; et al. Latest advances in in situ and operando X-ray-based techniques for the characterisation of photoelectrocatalytic systems. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024, 12, 23125-46.

42. Lin, S. C.; Chang, C. C.; Chiu, S. Y.; et al. Operando time-resolved X-ray absorption spectroscopy reveals the chemical nature enabling highly selective CO2 reduction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3525.

43. Díaz, J. J.; Kudriavtsev, Y.; Asomoza, R.; Mansurova, S.; Montaño, B.; Cosme, I. SIMS analysis of the degradation pathways of methylammonium lead-halide perovskites. Synth. Met. 2024, 307, 117705.

44. Baumann, S.; Eperon, G. E.; Virtuani, A.; et al. Stability and reliability of perovskite containing solar cells and modules: degradation mechanisms and mitigation strategies. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 7566-99.

45. Prete, M.; Khenkin, M. V.; Glowienka, D.; et al. Bias-dependent dynamics of degradation and recovery in perovskite solar cells. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2021, 4, 6562-73.

46. Bushuyev, O. S.; De Luna, P.; Dinh, C. T.; et al. What should we make with CO2 and how can we make it? Joule 2018, 2, 825-32.

47. Welch, A. J.; Digdaya, I. A.; Kent, R.; Ghougassian, P.; Atwater, H. A.; Xiang, C. Comparative technoeconomic analysis of renewable generation of methane using sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2021, 6, 1540-9.

48. Mamun, A. A.; Talukder, M. A. Techno-economic analysis of the direct solar conversion of carbon dioxide into renewable fuels. Energy. Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119038.

49. Yusuf, A. O.; Tekle, R. Y.; Amusa, H. K.; Palmisano, G. Technoeconomic assessment of photocatalytic methanol production from liquid CO2 using Cu-doped TiO2. Case. Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101172.

50. Francis, A. S., S. P.; S, H. K.; K, S.; Tahir, M. A review on recent developments in solar photoreactors for carbon dioxide conversion to fuels. J. CO2. Util. 2021, 47, 101515.

51. Zhang, K.; Gao, Q.; Xu, C.; et al. Current dilemma in photocatalytic CO2 reduction: real solar fuel production or false positive outcomings? Carb. Neutrality. 2022, 1, 10.

52. Gong, E.; Ali, S.; Hiragond, C. B.; et al. Solar fuels: research and development strategies to accelerate photocatalytic CO2 conversion into hydrocarbon fuels. Energy. Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 880-937.

53. Kovačič, Ž.; Likozar, B.; Huš, M. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction: a review of Ab initio mechanism, kinetics, and multiscale modeling simulations. ACS. Catal. 2020, 10, 14984-5007.

54. Yan, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, N.; et al. Systematic bandgap engineering of graphene quantum dots and applications for photocatalytic water splitting and CO2 reduction. ACS. Nano. 2018, 12, 3523-32.

55. Hou, J.; Cao, S.; Wu, Y.; et al. Inorganic colloidal perovskite quantum dots for robust solar CO2 reduction. Chemistry 2017, 23, 9481-5.

56. Mahyoub, S. A.; Hezam, A.; Qaraah, F. A.; et al. Surface plasmonic resonance and Z-scheme charge transport synergy in three-dimensional flower-like Ag-CeO2-ZnO heterostructures for highly improved photocatalytic CO2 reduction. ACS. Appl. Energy. Mater. 2021, 4, 3544-54.

57. Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; et al. Generating long-lived charge carriers in CdS quantum dots by Cu-doping for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 2234-40.

58. Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Ji, H.; et al. Construction of S-Co-S internal electron transport bridges in Co-doped CuInS2 for enhancing photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Mater. Today. Chem. 2022, 26, 101078.

59. Wang, J.; Xia, T.; Wang, L.; et al. Enabling visible-light-driven selective CO2 reduction by doping quantum dots: trapping electrons and suppressing H2 evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16447-51.

60. Yang, J.; Hou, Y.; Sun, J.; et al. Corn-straw-derived, pyridine-nitrogen-rich NCQDs modified Cu0.05Zn2.95In2S6 promoted directional electrons transfer and boosted adsorption and activation of CO2 for efficient photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 145142.

61. Raziq, F.; Hayat, A.; Humayun, M.; et al. Photocatalytic solar fuel production and environmental remediation through experimental and DFT based research on CdSe-QDs-coupled P-doped-g-C3N4 composites. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2020, 270, 118867.

62. Gao, L.; Xiao, W.; Qi, M.; Li, J.; Tan, C.; Tang, Z. Photoredox-catalyzed coupling of CO2 reduction and amines oxidation by Cu doped CdS quantum dots. Mol. Catal. 2024, 554, 113858.

63. Han, C.; Li, Y. H.; Li, J. Y.; Qi, M. Y.; Tang, Z. R.; Xu, Y. J. Cooperative syngas production and C-N bond formation in one photoredox cycle. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7962-70.

64. Cai, M.; Tong, X.; Liao, P.; et al. Manipulating the optically active defect-defect interaction of colloidal quantum dots for carbon dioxide photoreduction. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 15546-57.

65. Hou, W.; Guo, H.; Wu, M.; Wang, L. Amide covalent bonding engineering in heterojunction for efficient solar-driven CO2 reduction. ACS. Nano. 2023, 17, 20560-9.

66. Liu, J.; Ma, N.; Wu, W.; He, Q. Recent progress on photocatalytic heterostructures with full solar spectral responses. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 393, 124719.

67. Lin, J.; He, J.; Huang, Q.; et al. Interfacial Bi-O-C bonds and rich oxygen vacancies synergistically endow carbon quantum dot/Bi2MoO6 with prominent photocatalytic CO2 reduction into CO. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2025, 362, 124747.

68. Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; et al. Direct Z-Scheme 0D/2D Heterojunction of CsPbBr3 quantum dots/Bi2WO6 nanosheets for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020, 12, 31477-85.

69. Xu, F.; Meng, K.; Cheng, B.; Wang, S.; Xu, J.; Yu, J. Unique S-scheme heterojunctions in self-assembled TiO2/CsPbBr3 hybrids for CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4613.

70. Lu, M.; Li, Q.; Zhang, C.; et al. Remarkable photocatalytic activity enhancement of CO2 conversion over 2D/2D g-C3N4/BiVO4 Z-scheme heterojunction promoted by efficient interfacial charge transfer. Carbon 2020, 160, 342-52.

71. Ong, W.; Putri, L. K.; Tan, Y.; et al. Unravelling charge carrier dynamics in protonated g-C3N4 interfaced with carbon nanodots as co-catalysts toward enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction: a combined experimental and first-principles DFT study. Nano. Res. 2017, 10, 1673-96.

72. Xu, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, B.; Yu, J.; Xu, J. CuInS2 sensitized TiO2 hybrid nanofibers for improved photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2018, 230, 194-202.

73. Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Qi, M.; Tang, Z.; Xu, Y. Cooperative photoredox coupling of CO2 reduction with thiols oxidation by hybrid CdSe/CdS semiconductor quantum dots. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2025, 367, 125118.

74. Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, B.; Fan, J.; Yu, J. S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. Chem 2020, 6, 1543-59.

75. Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Xu, J. Embedding CsPbBr3 perovskite quantum dots into mesoporous TiO2 beads as an S-scheme heterojunction for CO2 photoreduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133762.

76. Wang, Y.; Fan, H.; Liu, X.; et al. 3D ZnO hollow spheres-dispersed CsPbBr3 quantum dots S-scheme heterojunctions for high-efficient CO2 photoreduction. J. Alloys. Compd. 2023, 945, 169197.

77. Hu, P.; Liang, G.; Zhu, B.; Macyk, W.; Yu, J.; Xu, F. Highly selective photoconversion of CO2 to CH4 over SnO2/Cs3Bi2Br9 heterojunctions assisted by S-scheme charge separation. ACS. Catal. 2023, 13, 12623-33.

78. Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhou, M.; Ou, S.; Liu, Y. Construction of a bismuthene/CsPbBr3 quantum dot S-scheme heterojunction and enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2022, 126, 3087-97.

79. Wang, L.; Cheng, B.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J. In situ irradiated XPS investigation on S-scheme TiO2@ZnIn2S4 photocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Small 2021, 17, e2103447.

80. Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Lai, C.; et al. BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) photocatalytic nanomaterials: applications for fuels and environmental management. Adv. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2018, 254, 76-93.

81. Muhammad, P.; Zada, A.; Rashid, J.; et al. Defect engineering in nanocatalysts: from design and synthesis to applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314686.

82. Du, C.; Sheng, J.; Zhong, F.; et al. Boosting exciton dissociation and charge transfer in CsPbBr3 QDs via ferrocene derivative ligation for CO2 photoreduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2024, 121, e2315956121.

83. Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Boosting photocatalytic CO2 reduction on CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals by immobilizing metal complexes. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 1517-25.

84. Sahm, C. D.; Ciotti, A.; Mates-Torres, E.; et al. Tuning the local chemical environment of ZnSe quantum dots with dithiols towards photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 5988-98.

85. Yu, R.; Ma, T.; Huang, X.; et al. Boosting CO2 photoreduction over perovskite quantum dots decorated with dispersed ruthenium nanoparticles. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2025, 687, 95-104.

86. Yang, J.; Song, N.; Du, C.; et al. Capture and photocatalytic conversion of low-concentration CO2 using a self-assembled CdSe@carbonic anhydrase biohybrid system. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202500856.

87. Wang, F.; Hou, T.; Zhao, X.; et al. Ordered macroporous carbonous frameworks implanted with CdS quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, e2102690.

88. Wu, J.; Deng, B. Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Assembling CdSe quantum dots into polymeric micelles formed by a polyethylenimine-based amphiphilic polymer to enhance efficiency and selectivity of CO2-to-CO photoreduction in water. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 29945-55.

89. Kong, Z.; Liao, J.; Dong, Y.; et al. Core@shell CsPbBr3@zeolitic imidazolate framework nanocomposite for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. ACS. Energy. Lett. 2018, 3, 2656-62.

90. Wu, T.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Application of QD-MOF composites for photocatalysis: energy production and environmental remediation. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 403, 213097.

91. Ding, L.; Bai, F.; Borjigin, B.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X. Embedding Cs2AgBiBr6 QDs into Ce-UiO-66-H to in situ construct a novel bifunctional material for capturing and photocatalytic reduction of CO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137102.

92. Ding, L.; Ding, Y.; Bai, F.; et al. In situ growth of Cs3Bi2Br9 quantum dots on Bi-MOF nanosheets via cosharing bismuth atoms for CO2 capture and photocatalytic reduction. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 2289-303.

93. Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Covalent organic framework photocatalysts: structures and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4135-65.

94. Wang, T.; Liang, H.; Anito, D. A.; Ding, X.; Han, B. Emerging applications of porous organic polymers in visible-light photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 7003-34.

95. He, Y.; Hu, P.; Zhang, J.; Liang, G.; Yu, J.; Xu, F. Boosting artificial photosynthesis: CO2 chemisorption and S-scheme charge separation via anchoring inorganic QDs on COFs. ACS. Catal. 2024, 14, 1951-61.

96. Cheng, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; et al. Confining quantum dots within covalent organic framework cages for coupled CO2 photoreduction and value-added chemical synthesis. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e12144.

97. Shen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Titanium carbide sealed cadmium sulfide quantum dots on carbon, oxygen-doped boron nitride for enhanced and durable photochemical carbon dioxide reduction. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 665, 443-51.

98. Guo, Z.; Barry, B. A. Calcium, ammonia, redox-active tyrosine YZ, and proton-coupled electron transfer in the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017, 121, 3987-96.

99. Badger, M. R.; Price, G. D. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 609-22.

100. Ünlü, A.; Duman-Özdamar, Z. E.; Çaloğlu, B.; Binay, B. Enzymes for efficient CO2 conversion. Protein. J. 2021, 40, 489-503.

101. Kim, C. U.; Song, H.; Avvaru, B. S.; Gruner, S. M.; Park, S.; McKenna, R. Tracking solvent and protein movement during CO2 release in carbonic anhydrase II crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016, 113, 5257-62.

102. DiMario, R. J.; Machingura, M. C.; Waldrop, G. L.; Moroney, J. V. The many types of carbonic anhydrases in photosynthetic organisms. Plant. Sci. 2018, 268, 11-7.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.