Molybdenum and fluorine co-doping induces lattice oxygen activation in Ni-Fe spinel oxides for enhanced oxygen evolution

Abstract

The oxygen evolution reaction (OER) is a critical process in electrochemical water splitting, yet challenging in activation of lattice oxygen oxidation mechanism (LOM) for cost-effective transition metal oxides, in which strong metal-oxygen (M-O) bonds inherently inhibit lattice oxygen reactivity. Here, we design a molybdenum/fluorine (Mo/F) co-dopant in NiFe2O4 spinel to engineer the electronic structure via an LOM pathway. The incorporation of high-valence Mo and highly electronegative F collaboratively optimizes the electronic configuration of Ni/Fe sites, facilitating the formation of stable high-valent metal species and effectively weakening the M-O bonds. This synergy not only results in faster OER kinetics but also promotes oxygen vacancy formation, thereby enabling direct lattice oxygen involvement. Real-time 18O-labeled differential electrochemical mass spectrometry coordinates with in-situ electrochemical impedance spectroscopy conclusively verify the activation of the LOM. The Mo/F-NiFe2O4 catalyst exhibits outstanding OER performance, requiring low overpotentials of 247 and 311 mV to achieve current densities of 50 and 100 mA cm-2, respectively. Remarkably, it demonstrates exceptional durability in seawater electrolytes, operating steadily for over 300 h at a high current density of 100 mA cm-2. This work provides a general and effective doping strategy to activate the LOM in robust oxide catalysts, paving the way for efficient hydrogen production from both pure water and seawater resources.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Green hydrogen, widely recognized as a clean and sustainable energy carrier, plays a pivotal role in the global transformation of the energy landscape[1-3]. The primary environmentally friendly and energy-effective strategy for large-scale production of hydrogen is water electrolysis driven by renewable energy sources[4-7]. However, the overall efficiency of this process is substantially constrained by the sluggish kinetics of the anodic oxygen evolution reaction (OER)[8-10] since it involves a complex four-electron transfer process. The sluggish kinetics necessitate high overpotentials in electrolyzers, leading to significant energy loss, not conducive to achieving global target of carbon peak and carbon neutrality[11-13]. This reaction predominantly follows the adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM), in which oxygen-containing intermediates are sequentially adsorbed and desorbed at the same active site on the catalyst surface[14,15]. This pathway establishes intrinsic linear scaling relationships among the adsorption energies of these intermediates, thereby imposing a fundamental thermodynamic overpotential limit on the OER[16,17]. To overcome this limitation, the lattice oxygen oxidation mechanism (LOM) has emerged as a promising alternative[18,19]. By enabling direct participation of lattice oxygen from the catalyst in molecular oxygen formation, LOM bypasses the scaling relations inherent in AEM and offers a viable route to significantly enhance intrinsic OER activity[20-22]. Therefore, developing earth-abundant, cost-effective catalysts capable of activating lattice oxygen is crucial for scalable water splitting technologies.

In recent years, spinel oxides, particularly iron-based spinel (e.g., FeCo2O4, NiFe2O4, etc.), have emerged as highly promising electrocatalysts for the OER due to their low cost, earth abundance, and excellent electrical conductivity[23-25]. However, their intrinsic stable electronic structures and strong metal-oxygen bonds typically constrain the OER to the conventional AEM pathway, which limits catalytic efficiency[26,27]. This fundamental limitation highlights the critical need for precise electronic structure modulation to weaken metal-oxygen bonding and facilitate lattice oxygen activation, thereby promoting the transition from AEM to the more favorable LOM[28,29]. Heteroatom doping is widely recognized as an effective approach to modulate the electronic structure and enhance catalytic activity[30-33]. Among various dopants, high-valence molybdenum (Mo) and highly electronegative fluorine (F) have drawn significant attention due to their unique electronic characteristics[34-37]. Specifically, high-valence Mo can partially substitute metal cations in AB2O4 spinel lattice, effectively altering the electronic distribution and creating electron-rich or electron-deficient domains of catalyst interface, thereby optimizing the intrinsic activity for water oxidation[38,39]. Concurrently, the strong electron-withdrawing nature of F tends to distort the M-O bonding network, which facilitates lattice oxygen activation and promotes the LOM pathway[40,41]. Furthermore, the large-scale application and commercialization of alkaline water electrolysis require catalysts with not only high intrinsic activity but also long-term stability under practical operating conditions. However, under high current density operation, catalytic performance is often limited by structural degradation. Therefore, the development of spinel-based catalysts featuring precisely engineered structures, enhanced catalytic efficiency, and exceptional durability is crucial for sustainable water splitting at industrially relevant current densities - yet significant challenges remain.

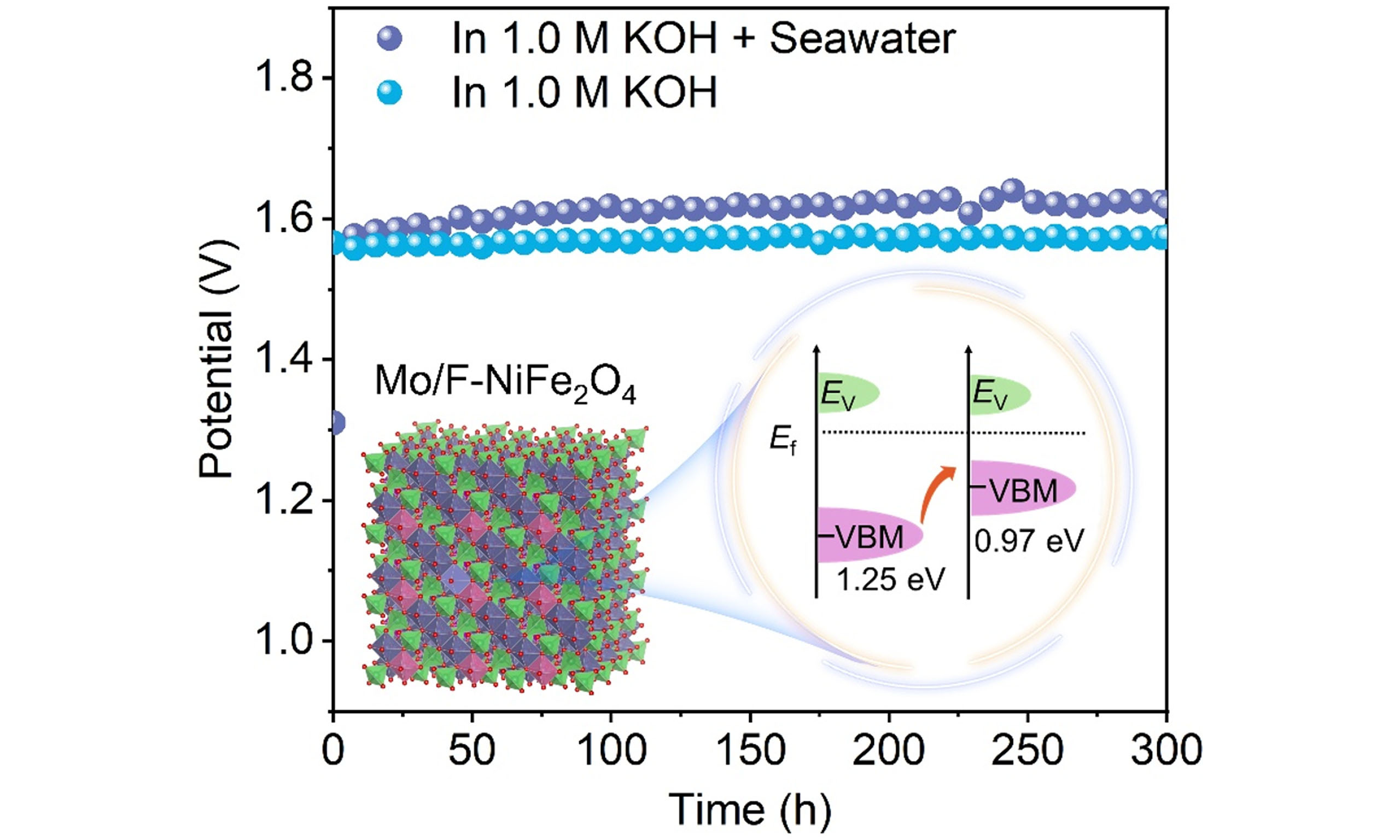

In this study, we introduced molybdenum and fluorine dopants into the nickel-iron-based spinel (Mo/F-NiFe2O4), aiming to enhance the oxygen evolution from a LOM pathway by cation-anion co-doping. Mo/F co-doping effectively elevates the valence band maximum of NiFe2O4, promoting activation of the LOM pathway during electrochemical OER. The Mo/F-NiFe2O4 catalyst shows excellent OER performance with low overpotentials of 247 and 311 mV to reach current densities of 50 and 100 mA cm-2, respectively. It also exhibits remarkable stability in seawater electrolytes, maintaining stable operation for over 300 h at

EXPERIMENTAL

Synthesis of Mo/F-NiFe2O4

First, nickel foam (NF) was pretreated and cut into pieces with size of 3 cm × 5 cm. 1.5 mmol of nickel nitrate hexahydrate, 3 mmol of ferric nitrate nonahydrate, 0.15 mmol of ammonium molybdate, 8 mmol of urea,

Comparative catalysts including Mo-NiFe2O4, F-NiFe2O4, and NiFe2O4 were synthesized via the same approach without introducing ammonium fluoride, ammonium molybdate, or both, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

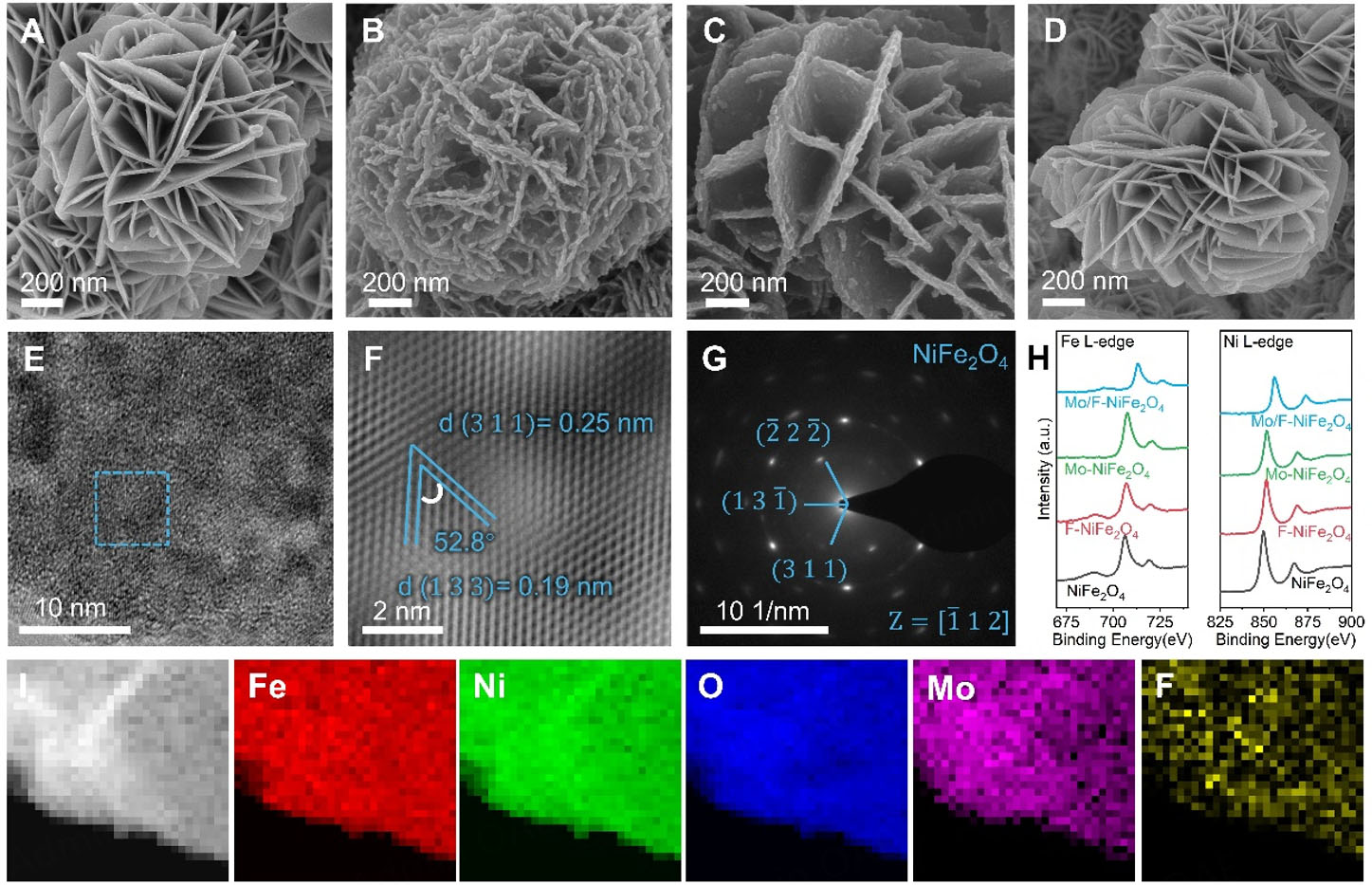

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was applied to study the microstructural evolution of various NiFe2O4-based catalysts. As illustrated in Figure 1A, pristine NiFe2O4 displays a flower-like morphology consisting of two-dimensional nanosheets with smooth surfaces. Upon Mo doping [Figure 1B], the overall flower-like architecture is retained; however, the nanosheets exhibit increased surface wrinkling and are decorated with small particles, resulting in enhanced surface roughness. In the case of F-doped NiFe2O4 [Figure 1C], the nanosheet-assembled flower-like structures demonstrate a significantly rougher surface, with well-distributed nanoparticles evident across the framework. In contrast, the Mo/F-NiFe2O4 [Figure 1D] preserves the flower-like morphology while displaying smoother, thinner and cleaner nanosheets, indicating that synergistic Mo and F co-doping effectively regulates the anisotropic growth of crystal planes. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) were further employed to investigate the detailed microstructure at higher magnifications. As shown in Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure 1A-D, all NiFe2O4-based catalysts exhibit nanosheet-like morphologies, consistent with the SEM observations. In Figure 1F, Mo/F-NiFe2O4 displays lattice fringes with spacings of 0.19 and 0.25 nm, which are assigned to the (1 3 3) and (3 1 1) planes of NiFe2O4, respectively, confirming its high crystallinity. This finding is further corroborated by the selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern in Figure 1G, where distinct diffraction spots can be indexed to the (

Figure 1. Morphology and structure characterizations of NiFe2O4-based catalysts. SEM images of (A) NiFe2O4, (B) Mo-NiFe2O4, (C)F-NiFe2O4 and (D) Mo/F-NiFe2O4; (E) TEM image, (F) iFFT-filtered HRTEM image, and (G) SAED pattern of Mo/F-NiFe2O4; (H) Ni L-edge and Fe L-edge EELS spectra of NiFe2O4, Mo-NiFe2O4, F-NiFe2O4 and Mo/F-NiFe2O4; (I) ADF-STEM and corresponding EELS maps of Mo/F-NiFe2O4.

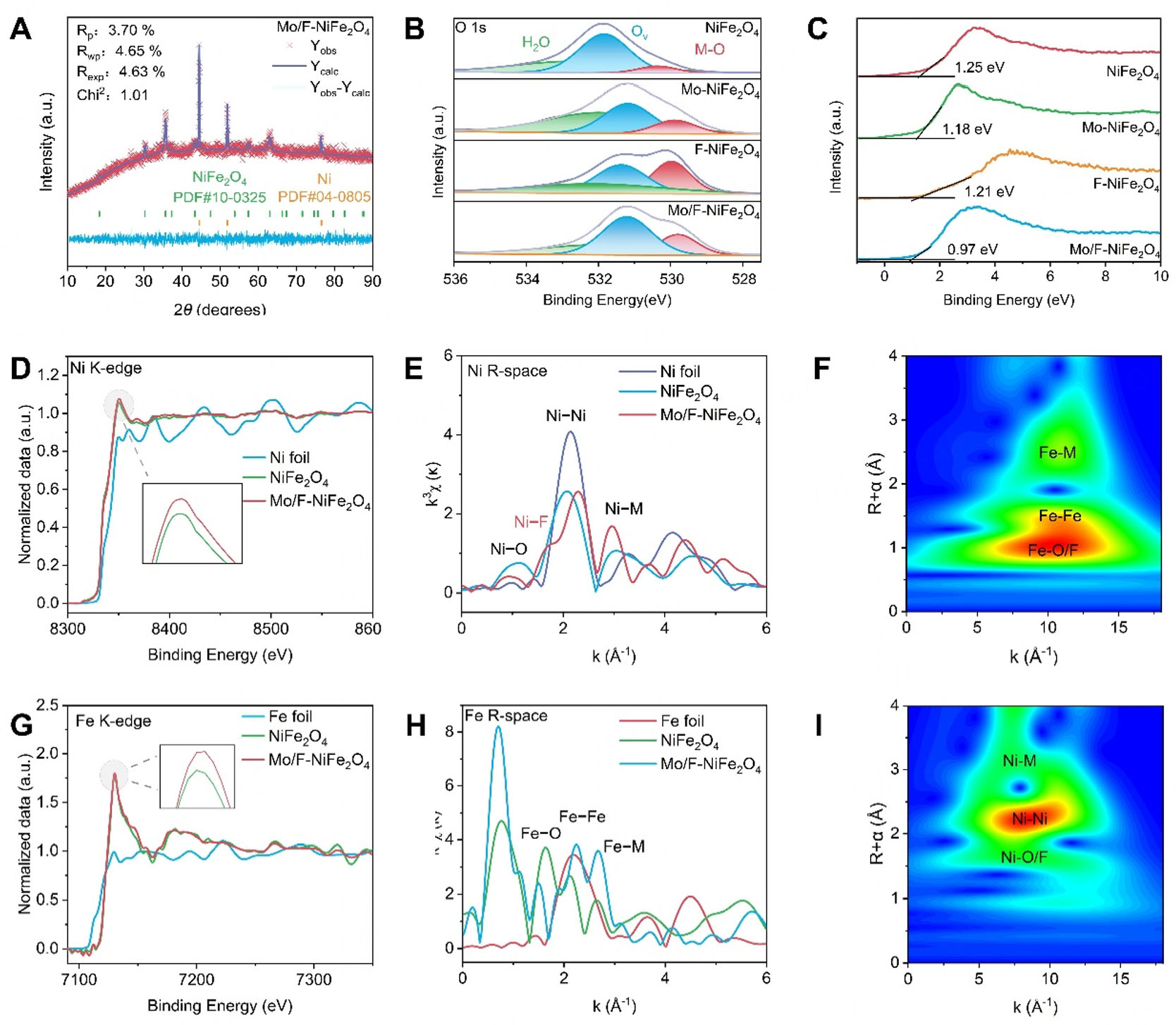

The phase structure and chemical composition of the NiFe2O4-based catalysts was further investigated at bulk aspects. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern shown in Supplementary Figure 5A displays diffraction peaks at 30.3°, 35.6°, and 63.1°, assigned to the (220), (311), and (440) crystal planes of NiFe2O4 spinel (PDF No. 10-0325), respectively. In addition, weak diffraction peaks observed at 44.2°, 51.2°, and 76.4° correspond to the (111), (200), and (220) planes of metallic Ni (PDF No. 04-0850), which are attributed to the underlying NF substrate. Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure 5, and Supplementary Table 1, the refined lattice parameter increased from 8.32163 Å (NiFe2O4) to 8.34101 Å for the Mo/F-NiFe2O4. This lattice expansion provides direct structural evidence for the successful incorporation of Mo and F into the spinel framework. To further verify the phase composition and surface chemical states, XPS measurements were performed. As shown in Supplementary Figure 6, the survey XPS spectrum confirms the presence of Ni, Fe, O, Mo, and F in the heteroatom-doped catalysts. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, relative to the undoped NiFe2O4 (23.29%), F-doping significantly increases the surface oxygen content (63.12%), while Mo-doping alone results in a considerably smaller change (29.45%). Importantly, the Mo/F co-doped catalyst attains an optimal, intermediate oxygen content (33.54%). This state of balance is of crucial importance as it adequately activates the lattice oxygen mechanism to boost activity while preventing excessive lattice oxygen that might undermine structural stability during operation[42]. High-resolution O 1s spectra of different catalysts are presented in Figure 2B, revealing three distinct peaks at 529.8, 531.2, and 532.3 eV, assigned to lattice oxygen (M-O), oxygen vacancies (OV), and adsorbed water species, respectively[43]. The specific atomic content of different oxygen species can be seen in Supplementary Table 3. Notably, the binding energy of the M-O peak gradually decreases with Mo and F doping. Specifically, the Mo/F-NiFe2O4 exhibits a 0.50 eV negative shift compared to pristine NiFe2O4, whereas the single-doped Mo-NiFe2O4 and F-NiFe2O4 samples display smaller shifts of 0.30 and 0.10 eV, respectively. As shown in

Figure 2. Physical properties of Mo/F-NiFe2O4. (A) XRD Rietveld refinement patterns; (B) High-resolution O 1s XPS spectrum; (C) XPS valence band spectrum; (D) XANES spectra of Ni K-edge; (E) Ni R-space EXAFS spectra; (F) WT analysis of Mo/F-NiFe2O4; (G) XANES spectra of Fe K-edge; (H) Fe R-space EXAFS spectra; (I) WT analysis of Mo/F-NiFe2O4.

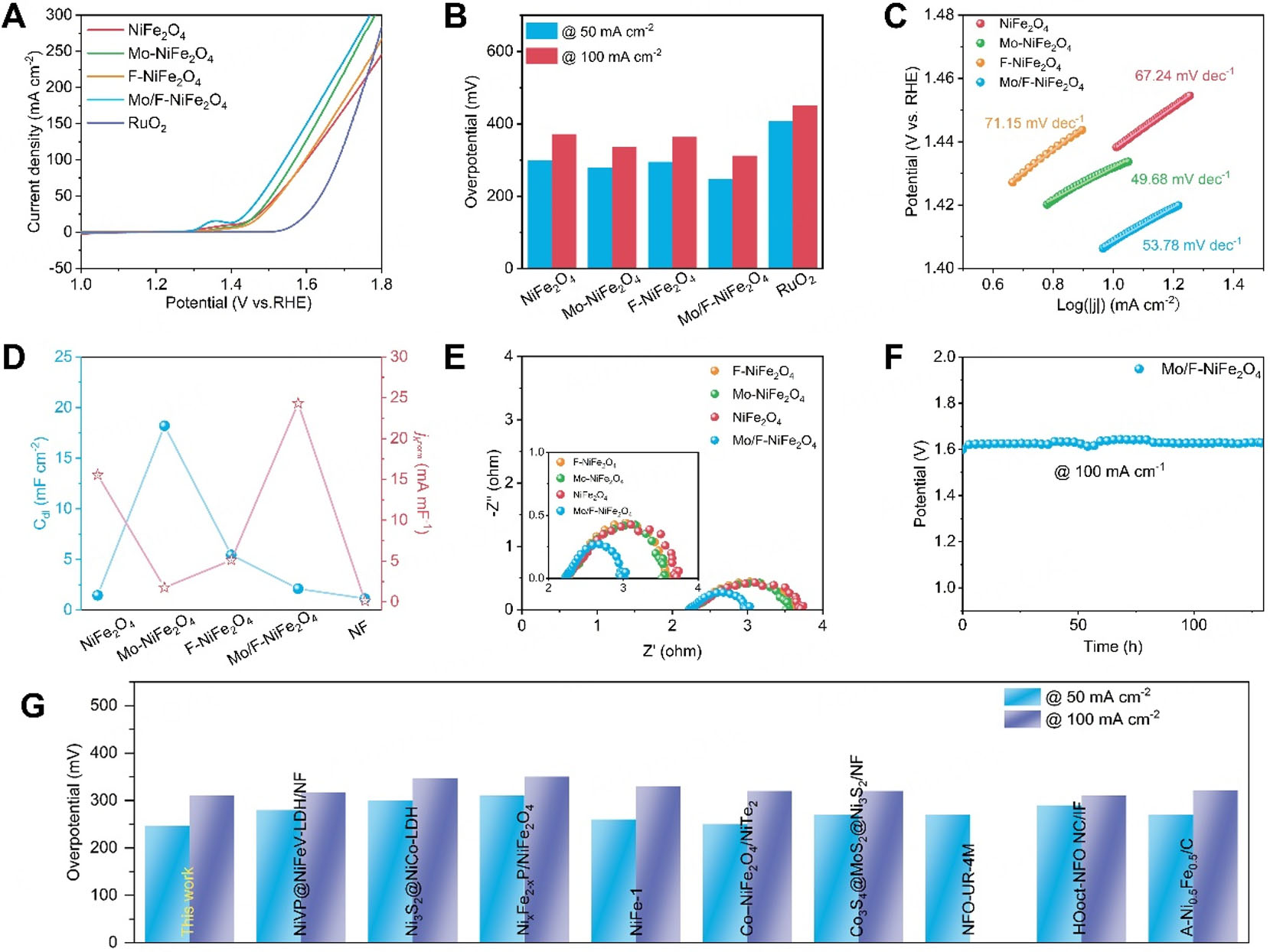

The electrocatalytic OER performance of the synthesized NiFe2O4-based catalysts and commercial RuO2 was evaluated in 1.0 M KOH solution. As shown from the polarization curves in Figure 3A and

Figure 3. OER catalytic performance of Mo/F-NiFe2O4. (A) Polarization curves; (B) Histogram of overpotentials at current densities of 50.0 and 100.0 mA cm-2; (C) Tafel plots; (D) Dot-line plots of Cdl (blue), and jKnorm (red) at potential of 1.48 V; (E) Nyquist plots; (F) Time-dependent potential curves at a constant current density of 100 mA cm-2 for over 130 h; (G) A comprehensive comparison of with recently reported other catalysts.

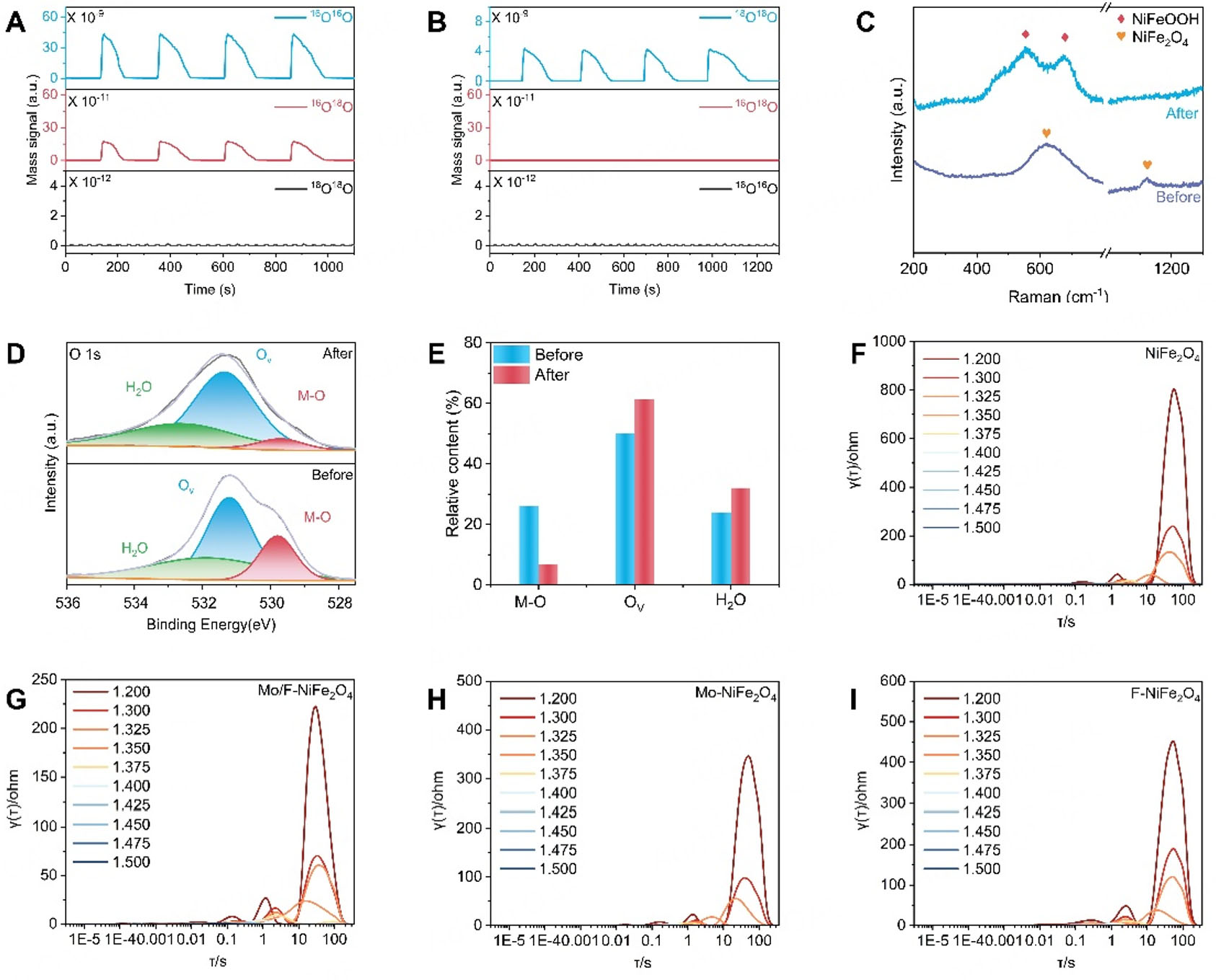

To verify whether Mo/F-NiFe2O4 activates the LOM during the OER, DEMS measurements were performed in real-time on both Mo/F-NiFe2O4 and pristine NiFe2O4 [Figure 4A and B]. Using 99.99% H218O as the solvent in a 1 M KOH electrolyte, a distinct signal was detected at m/z = 34 (16O18O) for Mo/F-NiFe2O4 during OER, whereas the signal at m/z = 36 (18O2) was negligible. In contrast, pristine NiFe2O4 showed no detectable signal at m/z = 34 but exhibited a prominent peak at m/z = 36 (18O2), indicating exclusive involvement of labeled oxygen from the electrolyte. These results clearly demonstrate that the synergistic modulation of Mo and F promotes the activation of the LOM in NiFe2O4 spinel, thereby significantly enhancing its intrinsic catalytic activity. To observe the structural evolution after the stability test, Raman spectroscopy was conducted before and after OER stability test. As clearly shown in Figure 4C, the pre-reaction sample displayed distinct characteristic peaks at approximately 621 and 1,154 cm-1, which corresponded to NiFe2O4. In sharp contrast, the post-reaction catalyst presented a double peak around 551 and 678 cm-1. Previous research findings indicate that these peaks correspond to the characteristic peaks of NiFeOOH, which strongly suggests a certain degree of surface reconstruction at the interface during the reaction[26]. To further confirm the occurrence of surface reconstruction, XPS characterization was carried out on Mo/F-NiFe2O4 before and after the OER stability test. As depicted in Figure 4D and E, the relative content of oxygen vacancy species in the post-reconstruction sample increased from 50.07% to 61.21%, whereas the content of lattice oxygen species decreased from 26.01% to 6.77%. This firmly confirms the occurrence of surface reconstruction and further validates the LOM pathway. Furthermore, to gain deeper insight into the kinetic behavior of the catalytic process, in situ EIS was conducted [Figure 4F-I]. Analysis of the relaxation time and impedance magnitude reveals that Mo/F-NiFe2O4 exhibits the lowest Rct and the fastest reaction kinetics among all catalysts, outperforming Mo-NFe2O4, F-NiFe2O4 and pristine NiFe2O4. These findings confirm that the superior intrinsic activity and accelerated reaction kinetics of Mo/F-iFe2O4 are directly attributed to the activation of the LOM.

Figure 4. Verification of the LOM pathway and interface changes of Mo/F-NiFe2O4. DEMS of (A) Mo/F-NiFe2O4 and (B) NiFe2O4; (C) Raman spectra ; (D) High-resolution XPS O 1s spectra; (E) Relative content of the different oxygen species of the Mo/F-NiFe2O4 before and after stability test; In-situ impedance testing diagram with corresponding relaxation time distribution diagram of (F) NiFe2O4, (G) Mo-NiFe2O4, (H) F-NiFe2O4 and (I) Mo/F-NiFe2O4.

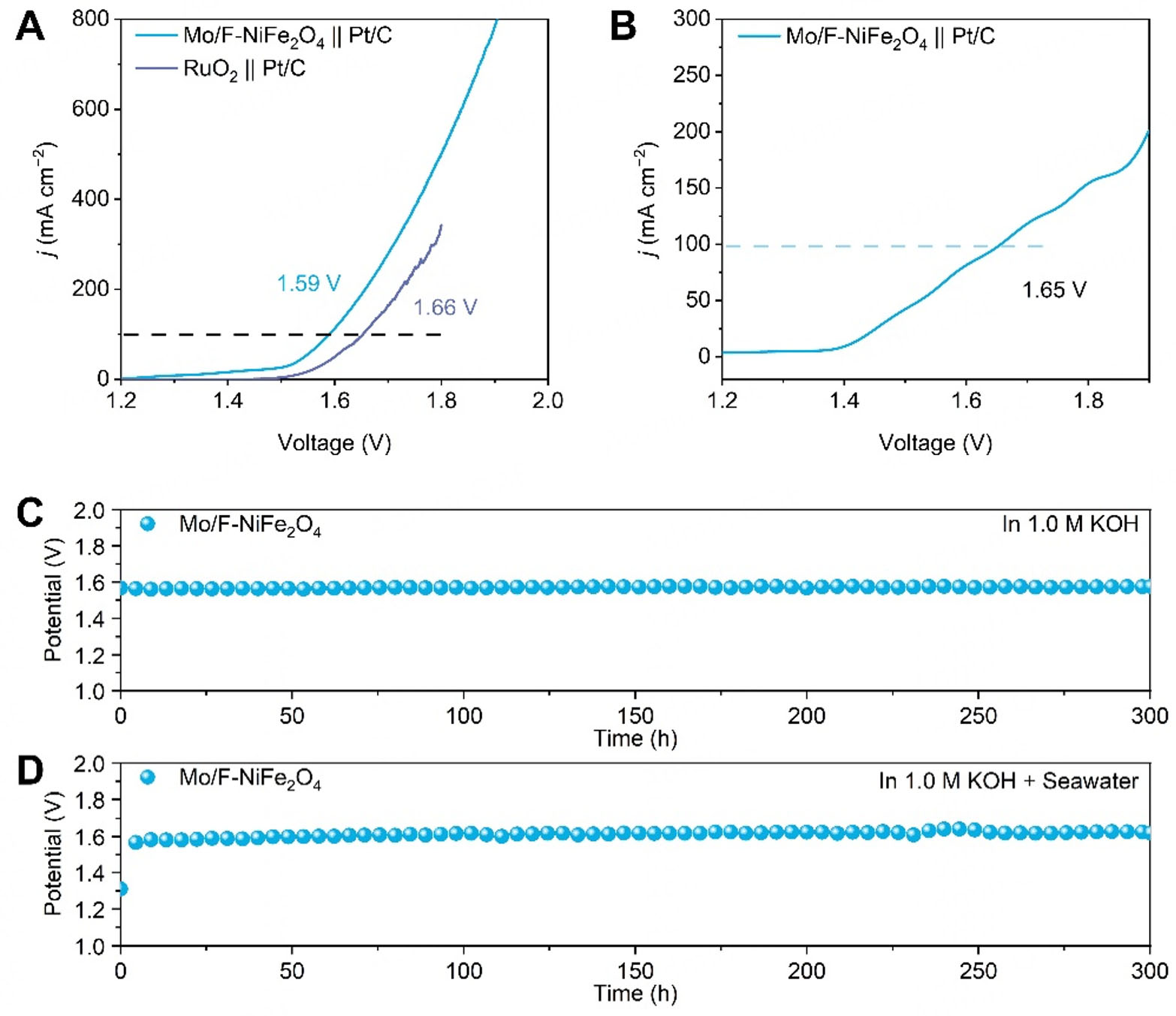

A two-electrode configuration was employed to evaluate the potential of the electrocatalyst for overall water splitting, in which the synthesized catalyst served as anode and commercial Pt/C as cathode. In this configuration, water oxidation occurs at the anode, where OH- ions are converted into O2, while hydrogen evolution takes place at the cathode, producing H2. Electrochemical measurements were performed in both 1.0 M KOH and alkaline seawater electrolytes. As shown in Figure 5A, under 1.0 M KOH conditions, the polarization curves of the optimized Mo/F-NiFe2O4 and commercial RuO2 were performed for comparison. Specifically, the overall water-splitting voltages for Mo/F-NiFe2O4 were 1.54 and 1.59 V at current densities of 50 and 100 mA cm-2, respectively, lower than those of commercial RuO2 (1.60 and 1.66 V). Meanwhile, as illustrated in Figure 5B, in alkaline seawater, Mo/F-NiFe2O4 achieved a current density of 100 mA cm-2 at only 1.65 V, highlighting its superior intrinsic catalytic activity. Considering working stability is another key criterion for assessing catalytic performance, the stability test at both alkaline and alkaline seawater electrolytes was performed. As shown in Figure 5C, the chronoamperometric test in 1.0 M KOH revealed that Mo/F Mo/F-NiFe2O4 exhibited negligible voltage fluctuations over 300 h of continuous operation. Similarly, Figure 5D demonstrates that under alkaline seawater conditions, Mo/F-NiFe2O4 maintained exceptional stability for more than 300 h at a high current density of 100 mA cm-2, demonstrating excellent adaptability to complex environments and practical potential for industrial production. Additionally, to further evaluate the catalyst’s resistance to chlorine-related side reactions and OER-related Faraday efficiency (FE), iodination colorimetric reaction was performed. As shown in Supplementary Figure 16, Mo/F-NiFe2O4 exhibited negligible color change after exposure to the post-reaction electrolyte solution. In contrast, RuO2 turned pale yellow after the stability test. This indicates that Mo/F-NiFe2O4 possesses excellent performance in suppressing competing chlorine (ClO-) side reactions. The oxygen FE of Mo/F-NiFe2O4 was calculated using the displacement gas collection method [Supplementary Equation 2]. The pre-reaction FE

Figure 5. Overall water splitting performance of Mo/F-NiFe2O4. (A) Polarization curves in 1.0 M KOH; (B) Polarization curves in 1.0 M KOH + Seawater; (C) Illustration of chronopotentiometric stability test in 1.0 M KOH. (D) Illustration of chronopotentiometric stability test in 1.0 M KOH + Seawater.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, Mo/F-NiFe2O4 was successfully constructed for the OER in alkaline media. Mo/F co-doping modulated the electronic structure, increased Ni/Fe oxidation states, and shifted the VBM upward, inducing electron redistribution and weakening metal-oxygen bonds, thereby facilitating M-O bond formation and cleavage during catalysis. Furthermore, Mo/F-NiFe2O4 catalyst effectively activated LOM, leading to accelerated reaction kinetics and enhanced intrinsic activity. Owing to these synergistic effects, the optimized Mo/F-NiFe2O4 catalyst delivered a low overpotential of 247 mV at 50 mA cm-2, and outstanding long-term stability over 130 h at 100 mA cm-2, surpassing both pristine NiFe2O4 and single-doped counterparts. Practical water-splitting in both alkaline and alkaline seawater demonstrated improved activity and stability. This work shows case insights into how dual anion-cation co-dopants in regulating lattice oxygen participation in the OER, offering valuable guidance for practical water electrolysis applications.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Qingdao Agricultural University for allowing the use of its facilities. We also thank Beijing SciStar Technology Co., Ltd. for XAFS measurements and analysis. Furthermore, Nicolosi, V. and Guo, X. acknowledge the Advanced Microscopy Laboratory (AML) at CRANN for access to their facilities.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to design of the study and performed writing: Min, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.

Assist in processing and analyzing data: Min, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Guo, X.; Nicolosi, V.

Collected literature: Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Cheng, Y.

Assist in collecting literature and researching the background: Min, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.

Made substantial contributions to conception of the study and provided financial support: Min, X.; Wang, J.

Revised the logic and grammar of the article: Nicolosi, V.; Wang, J.

Availability of data and materials

The relevant data and materials for the results of this study can be obtained from the first author or corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Nos. ZR2022QB028 and ZR2025MS141), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22202114), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province of China (No. 2024AFB870), the PhD Research Fund Project of Wuhan Business University (No. 2023KB009), and the project Research and Development of Testing Standards for Prohibited Substances in Sports Horses (No. 2024TD021). V.N. and X.G. acknowledge support from the Research Ireland-funded AMBER Research Centre and the SFI Frontiers for the Future program (Grant Nos. 12/RC/2278_P2 and 20/FFP-A/8950, respectively). V.N. and X.G. also acknowledge the Advanced Microscopy Laboratory (AML) at CRANN for access to facilities and thank Clive Downing for assistance with microscope optimization.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Yang, Y.; Li, P.; Zheng, X.; et al. Anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers and fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 9620-93.

2. Xu, H.; Yuan, J.; He, G.; Chen, H. Current and future trends for spinel-type electrocatalysts in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 475, 214869.

3. Yue, K.; Lu, R.; Gao, M.; et al. Polyoxometalated metal-organic framework superstructure for stable water oxidation. Science 2025, 388, 430-6.

4. Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Sun, A.; et al. Enhancing oxygen evolution electrocatalysis in heazlewoodite: unveiling the critical role of entropy levels and surface reconstruction. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2501186.

5. Lu, M.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; et al. Artificially steering electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction mechanism by regulating oxygen defect contents in perovskites. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq3563.

6. Li, P.; Mao, Y.; Shin, H.; et al. Tandem amine scrubbing and CO2 electrolysis via direct piperazine carbamate reduction. Nat. Energy. 2025, 10, 1262-73.

7. Sun, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, W.; et al. Fabricating freestanding electrocatalyst with bismuth‐iron dual active sites for efficient ammonia synthesis in neutral media. EcoEnergy 2023, 1, 186-96.

8. Lu, Z.; Chen, G.; Siahrostami, S.; et al. High-efficiency oxygen reduction to hydrogen peroxide catalysed by oxidized carbon materials. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 156-62.

9. Luo, X.; Zhao, H.; Tan, X.; et al. Fe-S dually modulated adsorbate evolution and lattice oxygen compatible mechanism for water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8293.

10. Malinovic, M.; Paciok, P.; Koh, E. S.; et al. Size‐controlled synthesis of IrO2 nanoparticles at high temperatures for the oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Energy. Mater. 2023, 13, 2301450.

11. Mei, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; et al. MoZn-based high entropy alloy catalysts enabled dual activation and stabilization in alkaline oxygen evolution. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadq6758.

12. Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lei, F.; Xie, J.; Tang, B. High-entropy amorphous oxycyanide as an efficient pre-catalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 11981-4.

13. Xia, W.; Ming, C.; Shuang, L.; et al. Sea urchin-like La-doped MnO2 for electrocatalytic oxidation degradation of sulfonamide in water. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500150.

14. Zhang, G.; Pei, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Selective activation of lattice oxygen site through coordination engineering to boost the activity and stability of oxygen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202407509.

15. Zheng, W.; Liang, G.; Liu, Q.; et al. The promise of high-entropy materials for high-performance rechargeable Li-ion and Na-ion batteries. Joule 2023, 7, 2732-48.

16. Olowoyo, J. O.; Kriek, R. J. Recent progress on bimetallic-based spinels as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. Small 2022, 18, e2203125.

17. Liu, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. Multiple synergies on cobalt-based spinel oxide nanowires for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 655, 685-92.

18. Huang, Z. F.; Xi, S.; Song, J.; et al. Tuning of lattice oxygen reactivity and scaling relation to construct better oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3992.

19. Chang, C. W.; Ting, Y. C.; Yen, F. Y.; Li, G. R.; Lin, K. H.; Lu, S. Y. High performance anion exchange membrane water electrolysis driven by atomic scale synergy of non-precious high entropy catalysts. Energy. Mater. 2025, 5, 500117.

20. Seenivasan, S.; Kim, M.; Han, J. W.; Kim, D. Minimal doping approach to activate lattice oxygen participation in K2WO4 electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2024, 358, 124423.

21. Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Lu, T.; et al. Importing atomic rare-earth sites to activate lattice oxygen of spinel oxides for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202415306.

22. Hu, Z.; Wu, H.; Yong, X.; et al. Advances in dual-site mechanisms for designing high-performance oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. eScience 2025, 5, 100403.

23. Einert, M.; Sezen, H.; Wu, Q.; et al. NiFe2O4 spinel thin film electrocatalysts: ordered mesoporous networks for driving the oxygen evolution reaction. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2025, 8, 14218-29.

24. Feng, Z.; Wang, P.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Recent progress on NiFe2O4 spinels as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2023, 946, 117703.

25. Zhong, H.; Gao, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Ion irradiation inducing oxygen vacancy-rich NiO/NiFe2O4 heterostructure for enhanced electrocatalytic water splitting. Small 2021, 17, e2103501.

26. Tang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Active non-bonding oxygen mediate lattice oxygen oxidation on NiFe2O4 achieving efficient and stable water oxidation. Chin. J. Catal. 2025, 72, 164-75.

27. Avcl, Ö. N.; Sementa, L.; Fortunelli, A. Mechanisms of the oxygen evolution reaction on NiFe2O4 and CoFe2O4 inverse-spinel oxides. ACS. Catal. 2022, 12, 9058-73.

28. Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Z.; et al. Ag engineered NiFe-LDH/NiFe2O4 Mott-Schottky heterojunction electrocatalyst for highly efficient oxygen evolution and urea oxidation reactions. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 665, 313-22.

29. Peng, K.; Bhuvanendran, N.; Zhang, W.; Pasupathi, S.; Su, H. Strong interfacial coupling activates lattice oxygen of heterogeneous cerium hydroxide/nickel ferrite catalyst for robust oxygen evolution reaction performance. Composites. Part. B. Eng. 2026, 309, 113080.

30. Li, X.; Wang, M.; Fu, J.; Lu, F.; Li, Z.; Wang, G. Sulfurized NiFe2O4 electrocatalyst with in situ formed Fe-NiOOH nanoparticles to realize industrial-level oxygen evolution. Small 2024, 20, e2310040.

31. Yao, L.; Wu, X.; Geng, Z.; et al. Oxygen evolution reaction of amorphous/crystalline composites of NiFe(OH)x/NiFe2O4. ACS. Nano. 2025, 19, 5851-9.

32. Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; et al. Introducing phosphorus into spinel nickel ferrite to enhance lattice oxygen participation towards water oxidation electrocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. Energy. 2024, 355, 124116.

33. Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y.; et al. sp2/sp3-hybridized nitrogen-mediated electrochemical CO2 capture and utilization. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw6592.

34. Tao, Y.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H.; et al. Tuning electronic structure of hedgehog-like nickel cobaltite via molybdenum-doping for enhanced electrocatalytic oxygen evolution catalysis. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2024, 657, 921-30.

35. Yang, B.; Bai, Z. P.; Cui, R. D.; Zeng, X. F.; Wang, J. X. A facile Mo doping strategy for high‐entropy spinel oxide towards efficient oxygen evolution reaction. AIChE. J. 2025, 71, e70087.

36. Li, X.; Gou, J.; Bo, L.; et al. Quenching induced Cu and F co-doping multi-dimensional Co3O4 with modulated electronic structures and rich oxygen vacancy as excellent oxygen evolution reaction electrocatalyst. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2025, 690, 137288.

37. Yue, Y.; Zhong, X.; Sun, M.; et al. Fluorine engineering induces phase transformation in NiCo2O4 for enhanced active motifs formation in oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2418058.

38. Cheng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; et al. High-entropy spinel oxide nanoparticles with surface anionic Mo Species for seawater oxidation. ACS. Appl. Nano. Mater. 2025, 8, 14999-5007.

39. Ding, S.; Duan, J.; Chen, S. Recent advances of metal suboxide catalysts for carbon‐neutral energy applications. EcoEnergy 2024, 2, 45-82.

40. Hong, X.; Gao, Y.; Ji, M.; et al. Highly valent cobalt-manganese spinel nanowires induced by fluorine-doping for durable acid oxygen evolution reaction. J. Alloys. Compd. 2024, 1007, 176500.

41. Xiao, K.; Wang, Y.; Wu, P.; Hou, L.; Liu, Z. Q. Activating lattice oxygen in spinel ZnCo2O4 through filling oxygen vacancies with fluorine for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202301408.

42. Ping, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, L.; et al. Locking the lattice oxygen in RuO2 to stabilize highly active Ru sites in acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2501.

43. Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Song, R. Te-doped NiFe2O4 stabilized by amorphous carbon layers derived from one-step topological transitions of NiFe LDHs with significantly enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142604.

44. Xiang, W.; Hernandez, S.; Hosseini, P.; et al. Unveiling surface species formed on Ni-Fe spinel oxides during the oxygen evolution reaction at the atomic scale. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2501967.

45. Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; et al. Cation‐vacancy-induced reinforced electrochemical surface reconstruction on spinel nickel ferrite for boosting water oxidation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 35, 2417983.

46. He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, H.; Kang, X. Evolution of lattice defects in nickel ferrite spinel: Oxygen vacancy and cation substitution. J. Alloys. Compd. 2022, 917, 165494.

47. Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Jiang, J.; Fu, J.; Xu, Q. 2D NiFe2O4/Ni(OH)2 heterostructure-based self-supporting electrode with synergistic surface/interfacial engineering for efficient water electrooxidation. Small 2024, 20, e2405225.

48. Luong, T. N.; Doan, T. L. L.; Bacirhonde, P. M.; Park, C. H. A study on synthesis of an advanced electrocatalyst based on high-conductive carbon nanofibers shelled NiFe2O4 nanorods for oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2025, 99, 1108-18.

49. Triolo, C.; Moulaee, K.; Bellato, F.; et al. Interplay between alkaline water oxidation temperature, composition and performance of electrospun high-entropy non-equimolar (Cr,Mn,Fe,Co,Ni) oxide electrocatalysts. J. Power. Sources. 2025, 654, 237887.

50. Tan, J.; Ma, M.; Cheng, S.; et al. Isolated Mo-doped nickel-iron spinel catalyst with oxygen vacancy and high-density interfaces for oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energy. 2025, 137, 73-82.

51. Wu, W.; Liu, B.; Xu, X.; Jing, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Synergistically regulating the electronic structure and stabilizing the lattice oxygen of spinel cobalt oxide by Mo and Pr dual doping to enhance acidic oxygen evolution performance. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 12174-88.

52. Wang, Y.; Feng, H.; Chai, D. F.; et al. Rapid and in-depth reconstruction of fluorine-doped bimetallic oxide in electrocatalytic oxygen evolution processes. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2025, 684, 84-94.

53. Zhao, H.; Zhu, L.; Yin, J.; et al. Stabilizing lattice oxygen through Mn doping in NiCo2O4-δ spinel electrocatalysts for efficient and durable acid oxygen evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202402171.

54. Peng, Y.; Huang, C.; Huang, J.; et al. Filling octahedral interstices by building geometrical defects to construct active sites for boosting the oxygen evolution reaction on NiFe2O4. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2201011.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.