Evolving trends and drug class dynamics in drug-induced fatty liver disease over two decades

Abstract

Aim: Drug-induced fatty liver disease (DIFLD) is an increasing concern due to both new and existing medications. This study aims to analyze trends in drug associations with DIFLD, identify vulnerable populations, and provide insights for better prevention and management strategies.

Methods: Reports of steatotic liver disease (SLD) and liver failure from the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) for the period 2004-2023 were analyzed separately after deduplication per guidelines. Drugs were categorized by therapeutic class, and trends were assessed using linear regression. Subgroup analyses addressed age, sex and regional difference.

Results: Between 2004 and 2023, a total of 15,269 SLD cases were reported in FAERS, with annual cases increasing significantly from 481 in 2004 to 1,413 in 2023 (+46.00 cases/year). Among implicated drug classes, monoclonal antibodies (MAbs), antipsychotics, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs were the most frequently reported, with MAbs showing the most rapid increase in reporting rate (+11.77 cases/year). Adalimumab was the leading single drug linked to DIFLD, accounting for 5.81% of all reported cases. Subgroup analyses revealed that adults aged 18-64 years (75.65%) and females (59.12%) were the most affected populations. Notably, hypoglycemic agents showed a pronounced increase in female cases. The United States accounted for 45.44% of cases, with distinct drug-class patterns observed across regions.

Conclusion: This study reveals significant trends in the association between drugs and DIFLD and liver failure, stressing the need for region-specific pharmacovigilance and tailored interventions to mitigate risks and optimize treatment outcomes.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Drug-induced fatty liver disease (DIFLD) has emerged as a critical concern in the context of liver-related adverse drug reactions, characterized by the excess accumulation of lipids in hepatocytes[1]. According to the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network, approximately 27% of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) cases exhibit some degree of steatosis and liver damage[2]. The intrahepatocyte accumulation of triglycerides typically arises from an imbalance between lipid acquisition and disposal, involving increased de novo lipogenesis, reduced fatty acid β-oxidation, or impaired very low-density lipoprotein export[3]. These metabolic disturbances may be exacerbated by oxidative stress, endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction, and inflammatory signaling, thereby sensitizing the liver to further injury[4]. DIFLD is not only a manifestation of liver injury but may also progress to drug-induced steatohepatitis, which can further advance to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even liver failure[5,6]. As the therapeutic landscape continues to expand with the introduction of novel medications, understanding the trends and implications of drugs associated with DIFLD has become paramount for enhancing pharmacological safety and personalizing patient care[7]. Accurate tracking of the drugs implicated in DIFLD is essential for identifying at-risk populations and developing targeted preventive strategies.

With the continuous introduction of new medications, DIFLD has increasingly become a significant concern in the realm of drug safety. In recent years, numerous novel therapies have entered the market, including monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), which have shown potential side effects related to the induction of steatotic liver disease (SLD)[8,9]. Research indicates that these new agents may be associated with liver fat accumulation; for instance, certain studies have reported that patients receiving MAbs may experience abnormal liver function tests (LFTs), suggesting a possible link to the development of DIFLD[10]. Additionally, the use of DMARDs has also been implicated in fatty liver development, yet comprehensive studies on their long-term impacts remain scarce[11]. In parallel, traditional drug classes continue to play a significant role in the incidence of DIFLD[6,12]. Specific antipsychotics, such as olanzapine and clozapine, have been well-documented to correlate with SLD[13,14]. For example, Carli et al. noted in clinical practice, among atypical antipsychotics, olanzapine and clozapine are associated with the highest risk of metabolic syndrome[15]. Furthermore, Acetaminophen is also known to cause liver damage; it is crucial to monitor their effects on liver fat content. Leise et al. noted that acetaminophen is the most common example of a drug causing predictable DILI[16]. Given these findings, understanding the evolution of drug types associated with DIFLD is vital, especially in the context of emerging new medications. This understanding not only enhances the effectiveness of clinical monitoring but also allows for more personalized and safer treatment options. Thus, systematically reviewing and analyzing the changes in drug usage related to DIFLD over the past two decades is key to formulating effective prevention and intervention strategies.

This study addresses these pressing needs by analyzing data from the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) spanning from 2004 to 2023[17-19]. By examining the changing landscape of drug-related SLD and liver failure, this research aims to identify shifts in drug associations and assess demographic patterns in reported cases. The findings will serve as a foundation for developing preventive measures and tailored therapeutic strategies, ultimately improving outcomes for patients susceptible to DIFLD. Through this targeted investigation, we hope to provide a clearer understanding of DILI, contributing to the establishment of evidence-based guidelines for monitoring and managing this increasingly prominent condition.

METHODS

Data source

FAERS is a database maintained by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to collect reports of adverse events and side effects related to drugs and vaccines. These reports, submitted voluntarily by healthcare professionals, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and consumers, include information on side effects, drug interactions, allergic reactions, and other adverse outcomes. FAERS captures key details such as patient demographics, drug information, descriptions and severity of adverse events, and the timing of these incidents. Although primarily focused on the U.S. market, FAERS also includes reports from other countries. We analyzed reports related to SLD and liver failure extracted from the FAERS database (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers-database) spanning the period from 2004 to 2023.

Drug selection

To ensure the accuracy and relevance of our dataset, we applied stringent inclusion criteria. Drugs reported in FAERS were categorized into four patterns, namely PS (primary suspect), SS (second suspect), C (concomitant), and I (interacting). To improve accuracy, we selected drugs reported as PS and combined their trade names and generic names. We utilize the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 26.1 as the standard terminology[20]. In the medical dictionary for regulatory activities [MedDRA (https://www.meddra.org/)] browser, we searched for “Steatotic liver disease” and excluded lowest level terms (LLTs) associated with alcohol-related SLD, selecting “Hepatic Steatosis” for analysis. Similarly, liver failure terms were identified by searching “Hepatic Failure” and selecting the corresponding preferred terms for “Hepatic Failure”, “Acute on Chronic Liver Failure”, “Hepatorenal Failure”, “Acute Hepatic Failure”, “Chronic Hepatic Failure” and “Subacute Hepatic Failure”.

Data processing

The FAERS database, updated quarterly, includes seven key datasets: (1) demographic and administrative information (DEMO); (2) drug data (DRUG); (3) adverse drug reactions (REAC); (4) patient outcomes (OUTC); (5) reported sources (RPSR); (6) therapy start and end dates (THER); and (7) indications for drug administration (INDI). There are unavoidable cases of duplicate reporting in FAERS due to the characteristics of data updating. Because of the periodic data updates, duplicate reports are unavoidable. To enhance the reliability of our findings, we set the study period from January 1, 2004, to December 31, 2023, and removed duplicates following FDA guidelines[21,22]: prioritizing the most recent FDA_DT for identical case identifiers (CASEIDs), and selecting the higher PRIMARYID if both CASEID and FDA_DT were the same[23]. The deduplication rate was 1.10% for the overall population. The analysis aimed to identify the top 50 drugs associated with DIFLD and liver failure. The dataset was further stratified by age, gender, and geographic region, and drugs were classified by therapeutic categories to facilitate the analysis of temporal trends. Subgroup analyses focused on the top 50 drugs with defined classifications to provide deeper insights into shifts in drug types over time. For national-level analyses, only reports from 2005 to 2023 were included because the 2004 data contained no valid country information. Approximately 30% of reports lacked age information, and > 5% lacked geographic or sex information. For regression analyses stratified by age, sex, or country, missing values were handled by excluding cases with missing data in the variable of interest. For country-level analyses, we excluded both NA and “COUNTRY NOT SPECIFIED” entries, while for age and sex analyses, only NA values were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Linear regression models were employed to assess temporal trends in adverse event reporting, adjusting for potential confounders such as age, gender, and location. Annual signal strength was calculated to evaluate changes in case frequency over time. Individual drug trend analyses were conducted to identify key contributors to DIFLD and liver failure. Descriptive statistics summarize the demographic characteristics of the cases. Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 package in R, and all statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.3.2). Linear regression served as the primary tool for evaluating trends in the dataset. P-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant. Confounding variables, such as comorbidities, polypharmacy, and dose, were not accounted for due to limited availability of these data in FAERS.

RESULTS

Trends and demographics of SLD

Between the first quarter of 2004 and the fourth quarter of 2023, the FAERS received a total of 17,379,552 adverse event reports, of which 15,269 (0.88‰) were identified as SLD cases. Analysis shows a significant upward trend in DIFLD reports, with cases increasing from 481 in 2004 to 1,413 in 2023, reflecting an average annual increase of 46.00 cases [95% confidence interval (CI): 34.99, 57.01] [Figure 1]. The majority of patients with reported SLD were adults and females, with females accounting for 59.12% of cases [Table 1]. Notably, the top 50 drugs associated with SLD accounted for 47.54% (7,249/15,269) of all cases reported to the FAERS during the study period [Figure 2]. Based on functional classification, the primary drug categories linked to a rapid progression of SLD were MAbs, Antipsychotic agents and DMARDs [Table 2].

Figure 1. Trends in DIFLD cases reported to the FAERS and associated with top 50 drugs (2004-2023). The bar chart illustrates the total number of DIFLD cases reported to the FAERS (blue bars) and the cases associated with the top 50 drugs (orange bars) from 2004 to 2023. The red line represents the percentage of DIFLD cases caused by the top 50 drugs out of the total cases reported annually. We confirm the figure is original and does not require external copyright permission. DIFLD: Drug-induced fatty liver disease; FAERS: Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Figure 2. Reported cases of DIFLD associated with various drug classes from the FAERS database (2004-2023). The bar chart on the left represents the top 50 drugs linked to DIFLD cases, categorized by drug class. The donut chart on the right shows the distribution of DIFLD cases among the drug classes. We confirm that the figure is original and does not require external copyright permission. DIFLD: Drug-induced fatty liver disease; FAERS: Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; INF: interferon.

The top 50 drugs associated with reports of DIFLD to the FAERS from 2004 to 2023

| Drug name and rank | Total adverse reports | DIFLD reports (‰) | United States DIFLD reports (%) (n = 13,898†) | Maximum DIFLD reports in a year (year) | Median year [IQR]§ | Reported female (%) (n = 14,178†) | Age median [IQR] (n = 10,731†)§ |

| Overall database from 2004 to 2023 | 17,379,552 | 15,269 (0.88‰) | 6,315 (45.44%) | 1,413 (2023) | 2017 (9) | 8,382 (59.12%) | 52 (21) |

| Top 50 drugs combined | 4,413,500 | 7,249 (1.64‰) | 3,169 (47.89%) | 652 (2023) | 2017 (8) | 4,236 (63.44%) | 53 (20) |

| 1. Adalimumab | 582,570 | 887 (1.52‰) | 335 (51.78%) | 104 (2023) | 2017 (5) | 555 (64.99%) | 54 (18) |

| 2. Methotrexate | 120,681 | 557 (4.62‰) | 132 (24.35%) | 108 (2023) | 2019 (3) | 352 (67.05%) | 57 (16) |

| 3. Etanercept | 496,741 | 388 (0.78‰) | 227 (59.11%) | 41 (2023) | 2015 (6) | 251 (68.58%) | 53 (14) |

| 4. Infliximab | 162,429 | 260 (1.6‰) | 61 (25.52%) | 34 (2023) | 2015 (10.25) | 103 (51.76%) | 50 (21) |

| 5. Olanzapine | 41,452 | 246 (5.93‰) | 85 (39.72%) | 49 (2023) | 2010 (10) | 87 (36.55%) | 39 (17.25) |

| 6. Metformin | 63,720 | 205 (3.22‰) | 23 (12.5%) | 31 (2023) | 2019 (7) | 101 (52.88%) | 56 (22) |

| 7. Duloxetine | 48,269 | 197 (4.08‰) | 114 (60%) | 28 (2023) | 2011 (7) | 145 (75.13%) | 50 (15.75) |

| 8. Ustekinumab | 68,045 | 195 (2.87‰) | 40 (20.51%) | 38 (2023) | 2018 (4) | 84 (45.65%) | 50 (18) |

| 9. Atorvastatin | 76,957 | 182 (2.36‰) | 73 (46.79%) | 19 (2023) | 2011 (12) | 95 (55.23%) | 60 (15.75) |

| 10. Tofacitinib | 123,304 | 174 (1.41‰) | 135 (77.59%) | 45 (2023) | 2021 (3) | 149 (87.13%) | 60 (15.75) |

| 11. Secukinumab | 124,910 | 167 (1.34‰) | 36 (27.48%) | 39 (2023) | 2021 (3) | 88 (53.99%) | 55 (20) |

| 12. Oxybate | 59,083 | 153 (2.59‰) | 153 (100%) | 43 (2023) | 2021 (4) | 106 (69.28%) | 45 (12.75) |

| 13. Rebif‡ | 38,597 | 157 (4.07‰) | 97 (63.4%) | 21 (2023) | 2012 (6) | 124 (78.98%) | 49 (15.25) |

| 14. Tocilizumab | 52,483 | 154 (2.93‰) | 11 (7.19%) | 28 (2023) | 2019 (5) | 119 (79.33%) | 59 (14) |

| 15. Valsartan | 133,765 | 148 (1.11‰) | 23 (18.11%) | 27 (2023) | 2019 (8) | 86 (60.14%) | 62 (13) |

| 16. Avonex‡ | 109,597 | 154 (1.41‰) | 108 (80.6%) | 19 (2023) | 2011 (10) | 130 (84.42%) | 51 (14) |

| 17. Olmesartan | 16,100 | 153 (9.5‰) | 136 (88.89%) | 73 (2023) | 2018 (1) | 19 (57.58%) | 55.5 (14.5) |

| 18. Acetaminophen | 132,151 | 140 (1.06‰) | 49 (39.2%) | 31 (2023) | 2020 (7) | 87 (67.97%) | 45 (20.5) |

| 19. Alendronate | 29,735 | 130 (4.37‰) | 97 (75.78%) | 39 (2023) | 2013 (6) | 98 (89.09%) | 61 (21) |

| 20. Rofecoxib | 35,761 | 124 (3.47‰) | 88 (88%) | 74 (2011) | 2006 (1) | 60 (48.39%) | 56 (16) |

| 21. Quetiapine | 68,567 | 121 (1.76‰) | 57 (50%) | 18 (2023) | 2012 (9) | 59 (50.43%) | 40 (16.25) |

| 22. Clozapine | 85,324 | 116 (1.36‰) | 11 (10.38%) | 19 (2023) | 2012 (8.25) | 48 (42.48%) | 37.5 (17) |

| 23. Rituximab | 79,910 | 107 (1.34‰) | 6 (5.61%) | 22 (2023) | 2021 (4) | 44 (70.97%) | 59 (17.75) |

| 24. Sitagliptin | 24,564 | 110 (4.48‰) | 97 (88.18%) | 40 (2023) | 2015 (2) | 54 (49.09%) | 59 (14.5) |

| 25. Exenatide | 69,368 | 109 (1.57‰) | 85 (77.98%) | 25 (2023) | 2009 (5) | 69 (63.3%) | 57 (14.75) |

| 26. Fingolimod | 72,801 | 105 (1.44‰) | 24 (32%) | 20 (2023) | 2019 (4) | 74 (70.48%) | 43 (14.5) |

| 27. Aripiprazole | 59,989 | 102 (1.7‰) | 49 (48.04%) | 25 (2023) | 2017 (3) | 30 (32.26%) | 43 (21.5) |

| 28. Zoledronic acid | 17,206 | 98 (5.7‰) | 93 (95.88%) | 45 (2020) | 2013 (1) | 60 (61.22%) | 52.5 (15.25) |

| 29. Abatacept | 76,075 | 92 (1.21‰) | 15 (16.3%) | 17 (2023) | 2020 (3.25) | 70 (77.78%) | 58 (16) |

| 30. Rosuvastatin | 39,280 | 93 (2.37‰) | 49 (59.04%) | 9 (2023) | 2012 (10) | 47 (53.41%) | 62 (13) |

| 31. Natalizumab | 152,972 | 91 (0.59‰) | 64 (71.11%) | 14 (2023) | 2014 (8) | 68 (74.73%) | 48 (19.5) |

| 32. Risperidone | 70,323 | 86 (1.22‰) | 23 (30.67%) | 8 (2023) | 2011.5 (10.75) | 25 (32.47%) | 31.5 (17) |

| 33. Sertraline | 47,379 | 85 (1.79‰) | 11 (13.25%) | 17 (2023) | 2014 (9) | 45 (57.69%) | 48 (15) |

| 34. Leflunomide | 15,645 | 85 (5.43‰) | 9 (12.68%) | 14 (2023) | 2019 (13) | 69 (83.13%) | 59.5 (18.5) |

| 35. Citalopram | 38,756 | 81 (2.09‰) | 6 (8.7%) | 13 (2023) | 2011 (5) | 51 (66.23%) | 46 (12) |

| 36. Palbociclib | 74,181 | 66 (0.89‰) | 23 (34.85%) | 35 (2023) | 2023 (2) | 66 (100%) | 62.5 (16.25) |

| 37. Amlodipine | 45,051 | 75 (1.66‰) | 7 (9.46%) | 17 (2023) | 2019 (6.5) | 36 (56.25%) | 63 (17.25) |

| 38. Simvastatin | 26,006 | 74 (2.85‰) | 24 (35.82%) | 11 (2023) | 2014 (8) | 37 (50%) | 63 (9) |

| 39. Dimethyl fumarate | 104,376 | 71 (0.68‰) | 54 (76.06%) | 17 (2023) | 2020 (4) | 57 (82.61%) | 51 (12.75) |

| 40. Pegaspargase | 3,832 | 68 (17.75‰) | 44 (64.71%) | 19 (2023) | 2019 (4) | 15 (53.57%) | 19.5 (24.5) |

| 41. Nuvarin// | 17,630 | 70 (3.97‰) | 65 (92.86%) | 31 (2019) | 2014 (2) | 68 (100%) | 32 (9) |

| 42. Diclofenac | 62,675 | 66 (1.05‰) | 8 (12.12%) | 26 (2023) | 2021 (5.75) | 43 (82.69%) | 49 (26.75) |

| 43. Betaseron‡ | 18,580 | 68 (3.66‰) | 30 (46.88%) | 12 (2020) | 2010 (7) | 45 (68.18%) | 47.5 (13.25) |

| 44. Oxycontin | 106,753 | 66 (0.62‰) | 52 (98.11%) | 27 (2023) | 2020 (14.5) | 21 (31.82%) | 41 (13) |

| 45. Lomitapide | 3,522 | 64 (18.17‰) | 25 (39.68%) | 14 (2023) | 2020 (6) | 18 (66.67%) | 53 (16) |

| 46. Lenalidomide | 297,270 | 64 (0.22‰) | 57 (89.06%) | 15 (2023) | 2019 (6.25) | 31 (48.44%) | 66 (14) |

| 47. Pamidronate | 3,601 | 65 (18.05‰) | 61 (98.39%) | 26 (2014) | 2013 (1) | 48 (73.85%) | 55.5 (14.25) |

| 48. Risankizumab | 37,369 | 59 (1.58‰) | 34 (65.38%) | 33 (2023) | 2023 (1) | 25 (45.45%) | 60 (23.5) |

| 49. Pregabalin | 111,227 | 62 (0.56‰) | 23 (37.1%) | 11 (2023) | 2015 (10.75) | 39 (66.1%) | 56 (21.75) |

| 50. Esomeprazole | 66,918 | 59 (0.88‰) | 40 (72.73%) | 12 (2023) | 2014 (4) | 35 (63.64%) | 54 (18) |

The top 50 drugs associated with reports of DIFLD to the FAERS from 2004 to 2023 - drug classes

| Drug name | DIFLD reports (%) | United States DIFLD reports (%) (n = 13,898†) | Maximum DIFLD reports in a year (year) | Median year [IQR] | Reported female (%) (n = 14,178†)§ | Age median [IQR] (n = 10,731†) | Cases change per year (95%CI), P value* |

| MAbs | 1,920 (12.58%) | 587 (36.37%) | 216 (2023) | 2018 (6) | 1,086 (61.77%) | 54 (20) | 11.77 (10.12, 13.43) P = 1.36E-11 |

| Antipsychotic agents | 1,249 (8.18%) | 532 (45.55%) | 99 (2023) | 2014 (9) | 635 (53.01%) | 43 (20) | 0.15 (-1.35, 1.65) P = 8.38E-01 |

| DMARDs | 1,204 (7.88%) | 503 (42.95%) | 157 (2023) | 2018 (5) | 821 (71.7%) | 57 (16) | 7.33 (5.23, 9.44) P = 8.42E-07 |

| Hypoglycemic agents | 424 (2.76%) | 205 (50.87%) | 54 (2023) | 2015 (7) | 224 (54.63%) | 56 (19) | 1.04 (0.04, 2.03) P = 4.16E-02 |

| Lipid lowering agents | 413 (2.70%) | 171 (46.34%) | 34 (2023) | 2014 (11) | 197 (54.57%) | 61 (13) | 0.14 (-0.39, 0.68) P = 5.84E-01 |

| INF | 379 (2.48%) | 235 (66.95%) | 52 (2023) | 2011 (7) | 299 (79.31%) | 49 (14) | -0.74 (-1.56, 0.07) |

| Blood lowering agents | 373 (2.44%) | 166 (47.29%) | 94 (2023) | 2018 (4) | 138 (58.23%) | 61 (16.25) | 2.28 (0.81, 3.76) P = 4.40E-03 |

| NSAIDs and acetaminophen | 330 (2.16%) | 145 (49.83%) | 76 (2023) | 2014 (15) | 190 (62.5%) | 50 (19) | -0.08 (-1.76, 1.61) P = 9.26E-01 |

| Bisphosphonates | 293 (1.92%) | 251 (87.46%) | 77 (2023) | 2013 (2) | 206 (75.46%) | 56 (18.5) | 0.09 (-1.8, 1.98) P = 9.22E-01 |

| Chemotherapy agents | 198 (1.30%) | 124 (62.63%) | 42 (2023) | 2021 (4) | 112 (70.89%) | 60 (19.5) | 1.85 (1.18, 2.53) P = 1.87E-05 |

| Other | 522 (3.42%) | 284 (60.68%) | 77 (2023) | 2019 (7) | 350 (68.9%) | 50 (19) | 3.15 (2.18, 4.13) P = 2.33E-06 |

| Overall database from 2004-2023 | 15,269 | 6,315 (45.44%) | 1,413 (2023) | 2017 (9) | 8,382 (59.12%) | 52 (21) | 46.00 (34.99, 57.01) P = 6.38E-08 |

Drug trends in SLD

MAbs were the most frequently reported drug class associated with SLD, accounting for 12.58% of all related cases reported to the FAERS during the study period [Table 2]. The proportion of SLD cases linked to MAbs peaked in 2023, representing 15.29% of all reports that year. Antipsychotic medications followed, accounting for 8.18% of all cases, then DMARDs at 7.88%, hypoglycemic agents at 2.76%, Lipid lowering agents at 2.70%, interferon (INF) analogs at 2.48%, blood lowering agents at 2.44%, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen at 2.16%, Bisphosphonates at 1.92%, and chemotherapy agents at 1.30% [Table 2].

Linear regression analysis revealed varying trends in the SLD cases across the major drug categories [Figure 3A]. For MAbs, the SLD cases increased at an average annual rate of 11.77 (95%CI: 10.12, 13.43), rising from 14 in 2004 to 216 in 2023 [Figure 3B], outpacing all other drug categories. Linear regression analysis indicated an upward trend in the number of reports of DIFLD for MAbs, DMARDs, blood lowering agents, chemotherapy agents and hypoglycemic agents, reported in FAERS during the study period. Conversely, no drug categories showed a declining trend in their proportion of SLD cases. For other drug categories, such as Antipsychotic agents, Bisphosphonates, Lipid lowering agents, NSAIDs and acetaminophen, INF, the slope of case reports over time did not show significant change during the study period.

Figure 3. DIFLD reports linear regression analysis by drug classes. (A) Trends in the DIFLD reports associated with various drug categories from 2004 to 2023; (B) Summary table showing the average cases change per year in DIFLD reports across drug categories. The statistical significance of changes in each drug category is indicated by the P-value (P < 0.05 considered significant). We confirm that the figure is original and does not require external copyright permission. DIFLD: Drug-induced fatty liver disease; CI: confidence interval; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; FAERS: Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System; INF: interferon; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

For a single drug, Adalimumab was the most commonly reported in SLD cases, representing 5.81% of all relevant cases in the FAERS database (887 out of 15,269). Among the top 50 drugs, Adalimumab showed the most notable increase in reported DIFLD cases, with cases of SLD rising at an average annual rate of 4.97 (95%CI: 3.40, 6.54). The cases climbed from 1 in 2004 to 60 in 2023 [Supplementary Table 1].

Age-related differences in DIFLD

The median age of patients with SLD varied by drug, with most cases reported in individuals aged 18 to 64 years (75.65%). To better understand the impact of age, we categorized the data into three age groups: minors (under 18), adults (18-64), and elderly (65+).

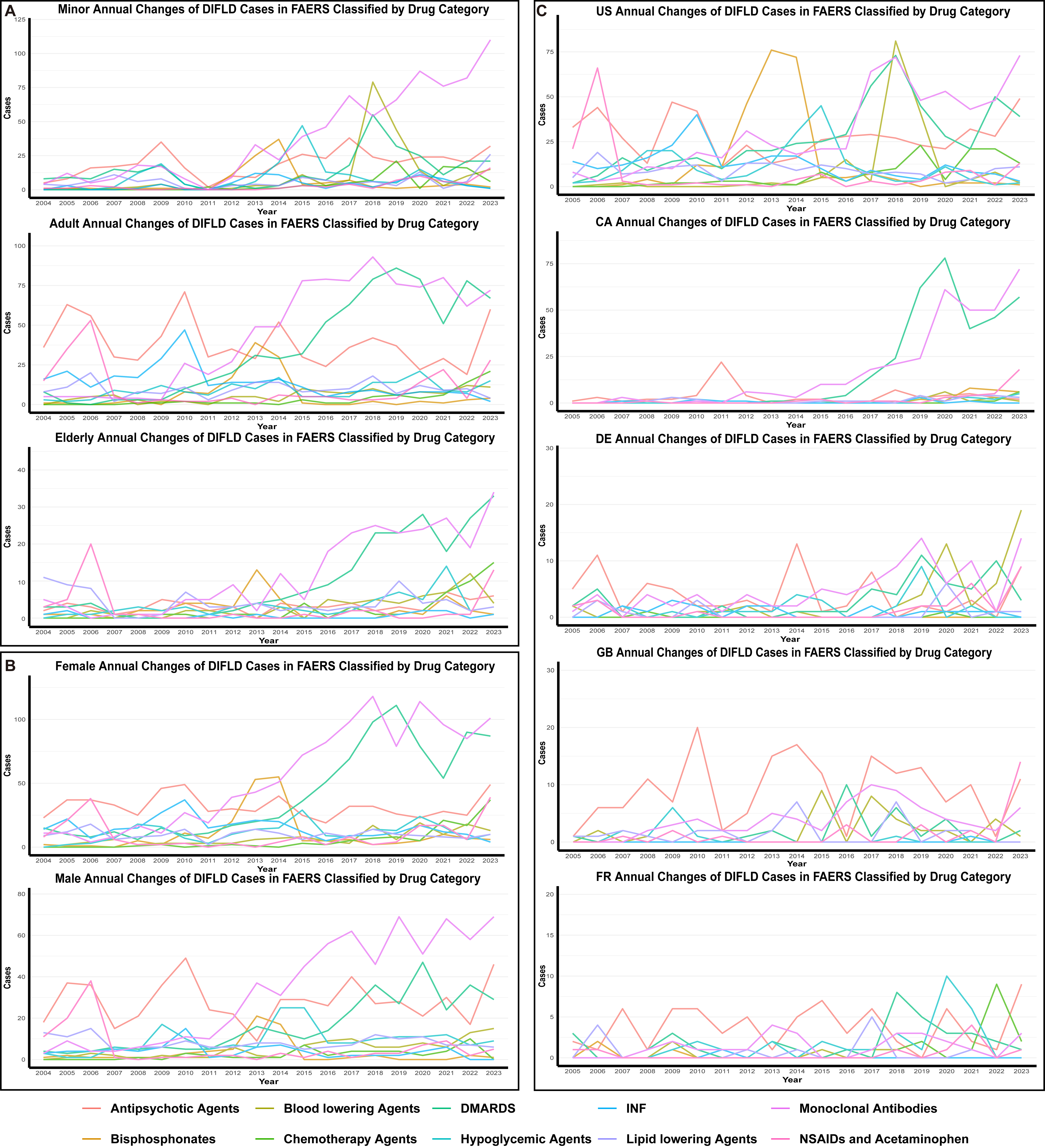

In minors, significant upward trends were observed for DMARDs (+0.20 annually), hypoglycemic Agents (+0.11 annually) and MAbs (+0.10 annually). Among adults, MAbs (5.03 annually), DMARDs (4.79 annually), chemotherapy agents (0.65 annually), hypoglycemic Agents (0.47 annually) and blood lowering agents (0.48 annually) showed the largest increase in reporting rates. Among the elderly, MAbs (1.63 annually), DMARDs (1.61 annually), chemotherapy agents (0.46 annually), blood lowering agents (0.40 annually), and hypoglycemic agents (0.28 annually) had the greatest annual increase in report counts [Figure 4A]. Notably, blood lowering agents were not reported in minors [Supplementary Table 2].

Figure 4. SLD reports linear regression analysis by drug classes in the country, age and gender group. (A) Trends in the DIFLD reports associated with various drug categories from 2004 to 2023 in age group; (B) Trends in the DIFLD reports associated with various drug categories from 2004 to 2023 in gender group; (C) Trends in the DIFLD reports associated with various drug categories from 2005 to 2023 in country group. Trends segmented by demographic groups, including males, females, elderly, and adults. Data represent annual case counts reported to the FAERS, illustrating temporal changes and potential impacts of different drug categories and patient populations on DIFLD reporting. We confirm that the figure is original and does not require external copyright permission. SLD: Steatotic liver disease; DIFLD: drug-induced fatty liver disease; FAERS: Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System; US: United States; CA: Canada; DE: Germany; GB: Great Britain; FR: France; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; INF: interferon; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Gender differences in DIFLD

A gender analysis revealed that female patients represented the majority of SLD cases for most drugs. Some drugs, such as Palbociclib, NuvaRing, Alendronate, and Tofacitinib, showed particularly high proportions of female cases, whereas others, including Olanzapine, Risperidone, Aripiprazole, and OxyContin, had a lower proportion of female cases. Overall, females accounted for 59.12% of the cases with known gender information [Table 1].

Gender-specific trends had the greatest annual increase in report counts among females for MAbs (6.23 annually), DMARDs (5.17 annually), chemotherapy agents (1.15 annually), blood lowering agents (0.73 annually), and hypoglycemic agents (0.52 annually). For males, MAbs (4.02 annually), DMARDs (1.92 annually), blood lowering agents (0.62 annually), hypoglycemic agents (0.40 annually) and chemotherapy agents (0.26 annually) exhibited notable upward trends [Figure 4B and Supplementary Table 3].

Geographic variations in DIFLD

Geographic distribution data were available starting in 2005. The United States accounted for 6,315 out of 13,898 (45.44%) of the reported SLD cases from all countries included in the FAERS database [Table 1]. Regional variations were observed in the proportion of cases linked to different drug categories. Notably, Bisphosphonates (87.46%), INF analogs (66.95%) and chemotherapy agents (62.63%) had a significantly higher proportion of reports from the United States compared to other countries, while drugs such as Rituximab, Tocilizumab, Citalopram, and Amlodipine had less than 10% of their cases reported from the United States [Table 2].

The five countries reporting the highest number of SLD cases were the United States (6,315 cases), Canada (1,535 cases), Germany (925 cases), the United Kingdom (772 cases), and France (726 cases). Regional analysis revealed distinct patterns. In the United States, increasing trends were observed in Mabs (3.49 annually), DMARDs (2.42 annually), chemotherapy agents (1.07 annually), while INF analogs (-0.77 annually) showed declining trends. In Canada, DMARDs (3.65 annually), Mabs (3.52 annually), NSAIDs and acetaminophen (0.44 annually), Bisphosphonates (0.32 annually), hypoglycemic agents (0.18 annually), Lipid lowering agents (0.16 annually), blood lowering agents (0.15 annually), and chemotherapy agents (0.13 annually) demonstrated increasing trends. Reports of blood lowering agents (0.54 annually), Mabs (0.48 annually), DMARDs (0.36 annually), NSAIDs and acetaminophen (0.19 annually) increased in Germany. In the United Kingdom, only MAbs (0.31 annually) exhibited increasing trend. In France, hypoglycemic drugs (0.21 annually) and chemotherapy agents (0.20 annually) showed a statistically significant increasing trend (P < 0.05) [Figure 4C]. Interestingly, there were no reports of Bisphosphonates in Germany or chemotherapeutic drugs in the United Kingdom, highlighting stark regional differences in reporting [Supplementary Table 4].

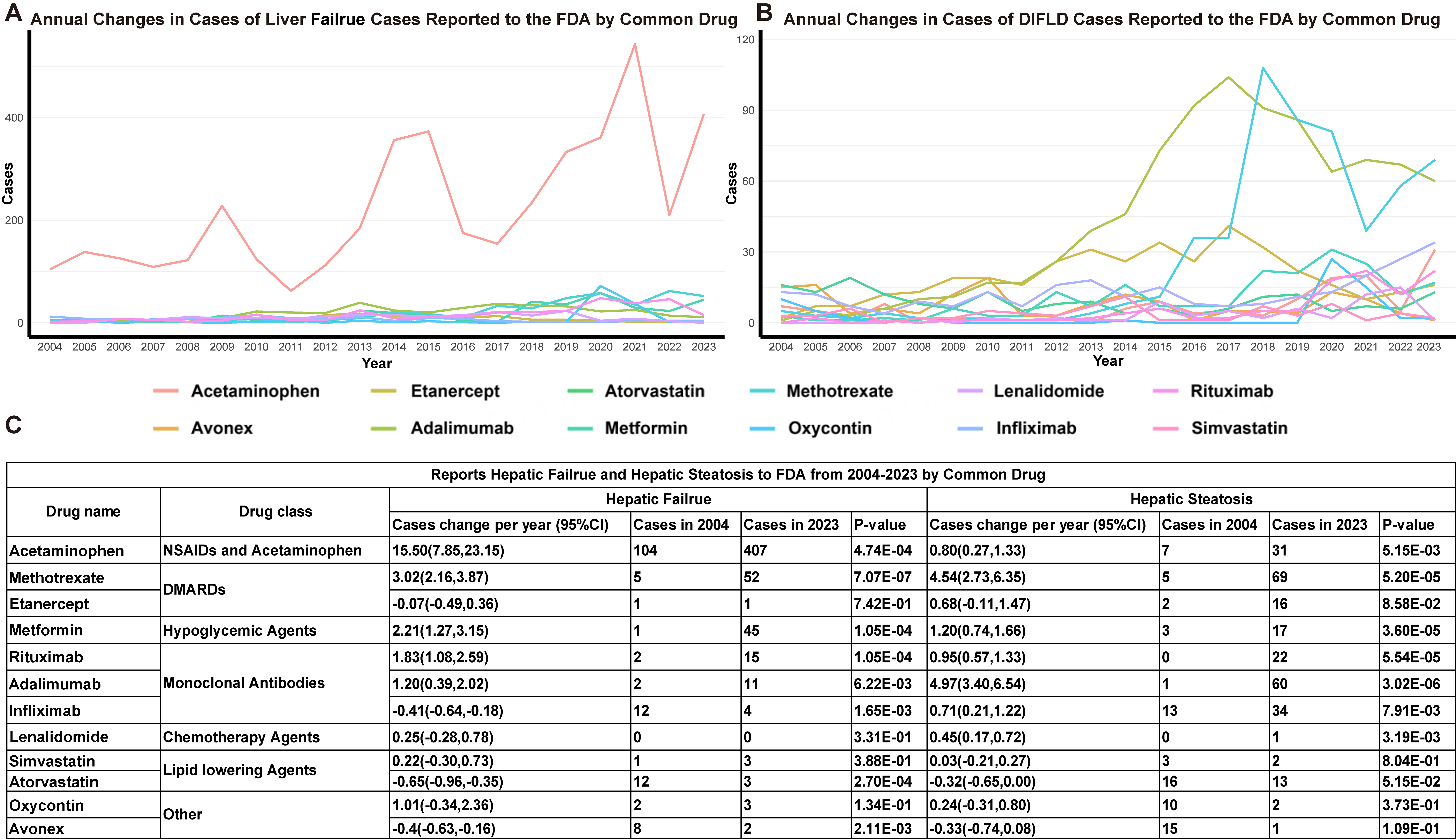

Trends and drug associations in liver failure

Between Q1 2004 and Q4 2023, 37,495 cases of liver failure were reported to FAERS, representing 0.22% (37,495 of 17,379,552) of all adverse events. Compared to DIFLD, liver failure was reported more frequently, with a consistent annual increase (linear regression β = 110.28 reports, 95%CI: 85.68-134.87). Annual reports rose from 1,079 in 2004 to 2,663 in 2023. Among the top 50 drugs associated with liver failure, Acetaminophen accounted for the highest proportion, with 4,455 reports (11.88%), followed by Ribavirin (1.16%), Sorafenib (1.15%), Ibuprofen (1.12%) and Methotrexate (1.09%). Twelve drugs appeared in the top 50 list for both SLD and liver failure [Table 3], including Acetaminophen, Methotrexate, Adalimumab, Metformin, Rituximab, Atorvastatin, Lenalidomide, Oxycodone, Etanercept, Infliximab, Avonex, and Simvastatin. Acetaminophen demonstrated the largest increase in liver failure reports (15.50 annually), growing from 104 cases in 2004 to 407 in 2023. Other significant increases were observed, in turn, for Methotrexate (3.02 annually), Metformin (2.21 annually), Rituximab (1.83 annually), and Adalimumab (1.20 annually), Lenalidomide (0.25 annually). Declining trends were only noted for Infliximab (-0.41 annually) [Figure 5].

Figure 5. DIFLD and Hepatic Failure reports linear regression analysis by common drug. (A) Year-over-year changes in DIFLD cases reported to the FAERS by common drugs from 2004 to 2023; (B) Year-over-year changes in hepatic failure cases reported to the FAERS by common drugs from 2004 to 2023; (C) The table summarizes the trends in hepatic failure and DIFLD cases reported to the FAERS from 2004 to 2023 for various drugs. It presents the cases change per year and the statistical significance (P-values) for both hepatic failure and steatosis. We confirm that the figure is original and does not require external copyright permission. DIFLD: Drug-induced fatty liver disease; FAERS: Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System; FDA: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; CI: confidence interval; NSAIDs: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; DMARDs: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

The top 50 drugs associated with reports of Hepatic Failure to the FAERS from 2004 to 2023

| Drug name | Hepatic Failure reports (%) | Drug name | Hepatic Failure reports (%) |

| 1. Acetaminophen | 4,455 (11.88%) | 26. Mycophenolate | 185 (0.49%) |

| 2. Ribavirin | 436 (1.16%) | 27. Lamotrigine | 166 (0.44%) |

| 3. Sorafenib | 433 (1.15%) | 28. Ciprofloxacin | 163 (0.43%) |

| 4. Ibuprofen | 420 (1.12%) | 29. Lamivudine | 161 (0.43%) |

| 5. Methotrexate | 410 (1.09%) | 30. Lenvatinib | 155 (0.41%) |

| 6. Adalimumab | 372 (0.99%) | 31. Carboplatin | 154 (0.41%) |

| 7. Sofosbuvir | 358 (0.95%) | 32. Pembrolizumab | 150 (0.40%) |

| 8. Metformin | 335 (0.89%) | 33. Oxycontin | 148 (0.39%) |

| 9. Tacrolimus | 329 (0.88%) | 34. Deferasirox | 148 (0.39%) |

| 10. Nivolumab | 329 (0.88%) | 35. Levetiracetam | 147 (0.39%) |

| 11. Rifaximin | 328 (0.87%) | 36. Etanercept | 147 (0.39%) |

| 12. Rituximab | 317 (0.85%) | 37. Dabigatran | 146 (0.39%) |

| 13. Bevacizumab | 312 (0.83%) | 38. Sunitinib | 146 (0.39%) |

| 14. Prednisolone | 285 (0.76%) | 39. Isoniazid | 142 (0.38%) |

| 15. Doxorubicin | 285 (0.76%) | 40. Ombitasvir | 141 (0.38%) |

| 16. Rifampicin | 284 (0.76%) | 41. Infliximab | 141 (0.38%) |

| 17. Amoxicillin | 238 (0.63%) | 42. Closporine | 140 (0.37%) |

| 18. Torvast | 229 (0.61%) | 43. Tracleer | 138 (0.37%) |

| 19. Ofloxacin | 224 (0.60%) | 44. Dexamethasone | 136 (0.36%) |

| 20. Amiodaron | 210 (0.56%) | 45. Bosentan | 133 (0.35%) |

| 21. Valproic acid | 204 (0.54%) | 46. Capecitabine | 132 (0.35%) |

| 22. Xarelto | 197 (0.53%) | 47. Metronidazole | 130 (0.35%) |

| 23. Rivaroxaban | 192 (0.51%) | 48. Atorvastatin | 125 (0.33%) |

| 24. Oxaliplatin | 189 (0.50%) | 49. Avonex | 125 (0.33%) |

| 25. Rosiglitazone | 187 (0.50%) | 50. Simvastatin | 123 (0.33%) |

DISCUSSION

This study systematically analyzed trends and characteristics of DIFLD reported in the FAERS from 2004 to 2023. The findings revealed a significant increase in the number of reported DIFLD cases, indicating growing awareness of this issue. Contrary to the traditional perspective that acetaminophen and methotrexate are the primary culprits of hepatotoxicity, our study highlighted the prominent reporting signal for various drug classes in recent years, particularly MAbs, DMARDs, and Antipsychotic agents, in the development of drug-induced SLD. Notably, the proportion of MAbs-associated cases increased markedly from 14 in 2004 to 216 in 2023, while DMARDs and other drug classes also demonstrated varying degrees of elevated risk. Moreover, differences across age groups, genders, and geographic regions underscored the complexity and heterogeneity of DIFLD. These findings expand our understanding of DIFLD and provide essential evidence for optimizing drug safety management and developing individualized intervention strategies.

Based on the study results, cases of DIFLD associated with MAbs have significantly increased. This rising trend coincides with the widespread use of MAbs in autoimmune diseases, cancers, and other inflammatory conditions[24-26]. While traditional drugs such as acetaminophen and methotrexate are considered major causes of hepatotoxicity[11,27], recent studies have shown that biologics are playing an increasingly important role in liver-related adverse events[28], which should not be overlooked. The potential mechanisms by which MAbs link to SLD are complex. Studies have found that MAbs, through interactions with liver immune cells, may trigger or exacerbate immune-mediated inflammatory responses. In particular, the activation of Kupffer cells and lymphocytes plays a significant role in liver injury and steatosis, with cytokines released by these cells inducing fat deposition in hepatocytes, leading to SLD[10,29,30]. Similarly, DMARDs, particularly methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors, have demonstrated a steady increase in cases of SLD. These drugs, often prescribed for autoimmune diseases, necessitate careful monitoring of liver function due to their hepatotoxicity[31,32]. Methotrexate-related liver injury has been linked to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in vitro[30]. Chemotherapy agents also contribute substantially, with reports indicating that up to 85% of patients may develop liver steatosis during treatment[33]. The underlying mechanism is primarily mitochondrial toxicity[34]. The rise in hypoglycemic agents, particularly in the context of diabetes management, has also contributed to increased reports of DIFLD, likely reflecting both the growing prevalence of diabetes and prolonged medication use. Certain hypoglycemic agents, such as pioglitazone, are specifically associated with an elevated risk of hepatotoxicity[35]. Moreover, insulin itself exerts lipogenic effects, and prolonged hyperinsulinemia may promote hepatic lipid storage[36]. Conversely, drug classes such as antipsychotics, Bisphosphonates, Lipid lowering agents, and NSAIDs did not show significant increases in SLD reports. This plateau likely reflects stable prescription rates and improved hepatic monitoring practices in psychiatric care. This stability suggests a consistent association with liver toxicity, though without an escalation in case proportions over time. Atypical antipsychotics, such as clozapine and olanzapine, are known to show a signal for metabolic syndrome and fatty liver, yet reports of these conditions have not significantly increased[14]. Likewise, NSAIDs and acetaminophen, though linked to acute hepatotoxicity, have not been strongly associated with chronic liver conditions such as steatosis. Interestingly, only INF displayed a declining trend. Interferon alpha (IFN-α) has been reported to induce SLD by elevating triglyceride levels through upregulation of ACSL1[37]. However, other studies suggest that such hepatic alterations are fully reversible once treatment is discontinued[38].

In examining the medication trends across age groups, it is clear that adults and the elderly share a common pattern in the increasing use of drugs such as DMARDs, MAbs and hypoglycemic drugs. These medications are integral to managing chronic conditions such as autoimmune diseases, cancer, and type 2 diabetes. The rising use of such therapies highlights the growing complexity in treating long-term health issues that require personalized and often multifaceted treatment strategies, especially in aging populations with multiple comorbidities. Notably, cases of liver steatosis caused by antihypertensive drugs are absent in the pediatric population, but there is a significant upward trend in both the adult and elderly populations. Additionally, the increased prescription of DMARDs and hypoglycemic medications in the pediatric population may reflect a shift in clinical practice toward treating autoimmune diseases and diabetes agents in younger individuals, emphasizing early diagnosis and management to reduce the burden of chronic disease later in life[39].

Our study also reveals significant gender differences in the development of DIFLD. Females represented a larger proportion (59.12%) of SLD cases among drugs with available gender data, a finding that is consistent with previous studies suggesting that women may be more susceptible to liver toxicity[40]. Physiological and hormonal factors, such as the effects of estrogen on liver enzyme activity, lipid metabolism, and drug metabolism, may explain this increased vulnerability[41]. Furthermore, women’s higher body fat percentage and different fat distribution patterns could amplify the hepatotoxic effects of lipophilic drugs[42]. Both male and female populations saw an increase in the use of MAbs, DMARDs, chemotherapy agents and antihypertensives, with females showing a more significant rise. MAbs and DMARDs, used to treat autoimmune diseases and cancer, induce liver injury in both genders. However, females are more likely to be diagnosed with autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, for which DMARDs and MAbs are commonly prescribed. This raises the possibility that the observed female predominance may not solely reflect biological susceptibility, but also differences in disease prevalence and prescribing practices, which may act as confounding factors. For instance, women are disproportionately affected by autoimmune disorders, leading to greater exposure to hepatotoxic therapies. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of considering both sex-based pharmacokinetic factors (e.g., liver enzyme activity, hormonal influences, fat distribution) and epidemiological or clinical factors (e.g., disease burden, treatment patterns) when interpreting gender differences in DIFLD risk. With the increasing use of hepatotoxic drugs, clinicians must remain vigilant, considering not only gender but also pharmacogenetic data and individual liver risks when prescribing treatments. Further research into the mechanisms underlying gender disparities is essential for improving drug safety and therapeutic interventions.

The analysis of SLD case reporting reveals both common and distinct drug classes contributing to liver-related adverse events across regions. Commonly, MAbs, DMARDs and chemotherapy agents show increasing trends in multiple countries, indicating a global rise in their use for treating autoimmune diseases, cancers, and inflammatory conditions. These drug classes are associated with higher SLD reports, which can be attributed to their widespread clinical use and known hepatotoxic effects. MAbs, in particular, have become a mainstay in cancer and autoimmune disease management, contributing to the higher incidence of hepatic adverse events[9,43]. On the other hand, there are distinct variations in regional drug patterns. For instance, Bisphosphonates, commonly used in osteoporosis treatment, show a notable increase in countries such as Canada but are absent in Germany’s reports. This could suggest differences in prescribing habits or underreporting in certain regions, where osteoporosis may be managed with alternative therapies. Similarly, the increasing trend of NSAIDs in Canada and Germany reflects the higher prescription rates of these drugs, which are often used for chronic pain and inflammation[44,45]. The rising incidence of SLD linked to NSAIDs in these regions could be attributed to their long-term use and associated liver toxicity. Interestingly, some drug classes show declining trends in certain countries. For example, INFs are increasingly replaced by more effective and less hepatotoxic therapies, leading to a decrease in related SLD cases, particularly in the United States[46]. It is important to note, however, that these regional differences may not solely reflect true variations in drug hepatotoxicity. Differences in reporting practices, healthcare access, and regulatory frameworks across countries could also contribute to the observed disparities. Overall, while certain drug classes show consistent patterns across regions, others, such as Bisphosphonates and NSAIDs, demonstrate significant regional differences. These findings highlight the influence of healthcare practices, prescribing trends, and local disease burdens on drug-induced hepatic adverse events. The observed regional differences in drug use and SLD reporting underscore the complexity of pharmacovigilance data and the influence of local healthcare practices, demographics, and therapeutic guidelines. These findings suggest that while global trends in DILI are evident, the specific drug classes contributing to adverse liver outcomes can vary significantly depending on national healthcare priorities, drug availability, and prescribing habits. These regional differences also highlight the need for tailored pharmacovigilance strategies and the importance of considering local clinical contexts when assessing the risks associated with drug use.

Importantly, this study identifies a concerning trend in drugs associated with liver failure. Acetaminophen, Methotrexate, Metformin, Rituximab, and Adalimumab all showed significant increases in liver failure reports over the study period. While Acetaminophen and Methotrexate are well-known hepatotoxins, the rising association of metformin and rituximab with liver failure is noteworthy, as these drugs are generally considered to have lower hepatic risk profiles. The parallel trends in liver failure and DIFLD for these drugs suggest that mechanisms such as mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and immune-mediated inflammation contribute to both conditions[47,48]. The overlapping trends call for tailored monitoring protocols to assess the risk of both SLD and failure in patients using these drugs. In contrast, drugs such as Infliximab, Atorvastatin, and Avonex, which showed a decline in liver failure reports, may reflect evolving treatment paradigms or improved safety profiles, reducing the incidence of these adverse effects. These findings highlight the need for integrated monitoring of both steatosis and liver function, particularly in long-term users. Early detection through imaging or biochemical tests may prevent progression to liver failure. In contrast, declining liver failure reports for infliximab and Avonex likely reflect improved safety or patient selection. By linking DIFLD with liver failure, our study emphasizes implementing routine imaging and liver enzyme monitoring for patients on high-risk drugs, allowing clinicians to detect steatosis early and intervene before liver failure develops.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of trends in DIFLD and liver failure using FAERS data from 2004 to 2023. A key strength is the large sample size, with 17,379,552 adverse event reports, including 15,269 cases of SLD, allowing for robust statistical analysis of drug-related liver toxicity. The longitudinal nature of the data enables the identification of trends over nearly two decades, revealing the increasing incidence of DIFLD and the trends of DLFLD among drug classes such as MAbs, antipsychotics, and DMARDs. Demographic factors such as age, gender, and geographic variation further enhance understanding of how these factors influence DIFLD. For instance, gender-specific analysis highlights female patients’ increased incidence of DIFLD, particularly those using DMARDs and MAbs. Beyond identifying trends, our findings provide actionable signals for clinicians. Specific drugs, such as Adalimumab, Tocilizumab, Methotrexate, and Rituximab, were associated with increasing reports of both DIFLD and liver failure. Clinicians should consider incorporating baseline SLD risk assessment when prescribing these medications. Enhanced monitoring of LFTs during therapy is recommended, particularly for patients receiving long-term or combination therapy. For example, periodic imaging or biochemical assessments could help detect early steatotic changes and allow timely interventions to prevent progression to severe liver injury. Conversely, drugs such as Infliximab, which showed decreasing trends in DIFLD reporting, may present a comparatively lower risk but still warrant routine hepatic monitoring. Taken together, these results emphasize the importance of mechanism-informed, proactive monitoring strategies tailored to specific drugs and patient characteristics. By integrating these findings into clinical decision-making, healthcare providers can better anticipate and mitigate the risk of DIFLD and liver failure, ultimately improving patient safety.

Despite the above strengths, this study has several limitations. FAERS is a spontaneous reporting system subject to underreporting, selective reporting, and overrepresentation of severe cases, which may introduce reporting bias and limit generalizability, particularly across different regions and in pediatric populations where reports are scarce. Incomplete information on patient demographics, comorbidities, concomitant drugs, dosage, and treatment duration further constrains interpretation, while the absence of detailed clinical outcomes (e.g., severity or mortality) restricts assessment of clinical significance. Restricting analyses to primary suspect drugs reduces confounding but may overlook relevant drug–drug interactions. Moreover, FAERS data only allow associations to be identified, not causal inference. Finally, although demographic and drug-class trends were comprehensively discussed, the mechanistic explanations remain limited. Specifically, the current analysis cannot fully account for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variability, genetic susceptibility, or immunological mechanisms underlying drug-induced fatty liver and liver failure. Integrating pharmacological data, experimental models, and clinical cohorts in future research will be essential to contextualize observed trends and strengthen causal understanding.

DECLARATIONS

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the FAERS for providing access to the adverse event reporting data, which was essential for our analysis. Their commitment to public health and safety greatly facilitated our research on drug-induced SLD.

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, methodology and writing - original draft: Xiang H, Wang W, Miao Z, Dong H

Made substantial contributions to conceptualization, data curation, supervision, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology and writing - original draft: Yan G, Fan X, Gao L

Writing - review and editing: Fan X, Gao L

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The FAERS database used in this study is publicly accessible and can be obtained from the U.S. FAERS website (https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/fda-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers-database).

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 82200659), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR20220H002) and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation for The Excellent Youth Scholars (Grant No. ZR2024YQ011).

Conflicts of interest

Fan X is the Junior Editorial Board Member of the journal Metabolism and Target Organ Damage. Fan X was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewers’ selection, manuscript handling and decision making. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Since the FAERS database is accessible to the public and patient records are anonymized and de-identified, ethical clearance and informed consent are not required for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. López-Pascual E, Rienda I, Perez-Rojas J, et al. Drug-induced fatty liver disease (DIFLD): a comprehensive analysis of clinical, biochemical, and histopathological data for mechanisms identification and consistency with current adverse outcome pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:5203.

2. Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, et al; Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN). Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology. 2014;59:661-70.

3. Ipsen DH, Lykkesfeldt J, Tveden-Nyborg P. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic lipid accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:3313-27.

4. Begriche K, Massart J, Robin MA, Bonnet F, Fromenty B. Mitochondrial adaptations and dysfunctions in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013;58:1497-507.

5. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al; American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterologyh. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1592-609.

6. Kolaric TO, Nincevic V, Kuna L, et al. Drug-induced fatty liver disease: pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2021;9:731-7.

7. Hosack T, Damry D, Biswas S. Drug-induced liver injury: a comprehensive review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231163410.

9. Hansel TT, Kropshofer H, Singer T, Mitchell JA, George AJ. The safety and side effects of monoclonal antibodies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:325-38.

10. Pfefferlé M, Dubach IL, Buzzi RM, et al. Antibody-induced erythrophagocyte reprogramming of Kupffer cells prevents anti-CD40 cancer immunotherapy-associated liver toxicity. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e005718.

11. Bath RK, Brar NK, Forouhar FA, Wu GY. A review of methotrexate-associated hepatotoxicity. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:517-24.

12. Di Pasqua LG, Cagna M, Berardo C, Vairetti M, Ferrigno A. Detailed molecular mechanisms involved in drug-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: an update. Biomedicines. 2022;10:194.

13. Todorović Vukotić N, Đorđević J, Pejić S, Đorđević N, Pajović SB. Antidepressants- and antipsychotics-induced hepatotoxicity. Arch Toxicol. 2021;95:767-89.

14. Slim M, Medina-Caliz I, Gonzalez-Jimenez A, et al. Hepatic safety of atypical antipsychotics: current evidence and future directions. Drug Saf. 2016;39:925-43.

15. Carli M, Kolachalam S, Longoni B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome: from molecular mechanisms to clinical differences. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:238.

16. Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA. Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:95-106.

17. Anand K, Ensor J, Trachtenberg B, Bernicker EH. Osimertinib-induced cardiotoxicity: a retrospective review of the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS). JACC CardioOncol. 2019;1:172-8.

18. Kamimura H, Setsu T, Kimura N, et al. Analysis of drug-induced liver-related adverse event trend reporting between 1997 and 2019. Hepatol Res. 2023;53:556-68.

19. Yang Z, Lv Y, Yu M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonist-associated tumor adverse events: a real-world study from 2004 to 2021 based on FAERS. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:925377.

20. Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Saf. 1999;20:109-17.

21. Shu Y, He X, Liu Y, Wu P, Zhang Q. A real-world disproportionality analysis of Olaparib: data mining of the public version of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Clin Epidemiol. 2022;14:789-802.

22. Wang Y, Zhao B, Yang H, Wan Z. A real-world pharmacovigilance study of FDA adverse event reporting system events for sildenafil. Andrology. 2024;12:785-92.

23. Cui Z, Cheng F, Wang L, et al. A pharmacovigilance study of etoposide in the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database, what does the real world say? Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1259908.

24. Posner J, Barrington P, Brier T, Datta-Mannan A. Monoclonal antibodies: past, present and future. In: Barrett JE, Page CP, Michel MC, editors. Concepts and principles of pharmacology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 81-141.

25. Boyiadzis M, Foon KA. Approved monoclonal antibodies for cancer therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008;8:1151-8.

26. Perosa F, Luccarelli G, Prete M, Dammacco F. Monoclonal antibodies in the immunotherapy of autoimmune diseases. Ann Ital Med Int. 2001;16:220-32.

27. Chun LJ, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW, Hiatt JR. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:342-9.

28. De Martin E, Michot JM, Rosmorduc O, Guettier C, Samuel D. Liver toxicity as a limiting factor to the increasing use of immune checkpoint inhibitors. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100170.

29. Chen J, Deng X, Liu Y, et al. Kupffer cells in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: friend or foe? Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:2367-78.

30. Schmidt S, Messner CJ, Gaiser C, Hämmerli C, Suter-Dick L. Methotrexate-induced liver injury is associated with oxidative stress, impaired mitochondrial respiration, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15116.

31. Di Martino V, Verhoeven DW, Verhoeven F, et al. Busting the myth of methotrexate chronic hepatotoxicity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023;19:96-110.

32. French JB, Bonacini M, Ghabril M, Foureau D, Bonkovsky HL. Hepatotoxicity associated with the use of anti-TNF-α agents. Drug Saf. 2016;39:199-208.

33. Ramadori G, Cameron S. Effects of systemic chemotherapy on the liver. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:133-43.

35. Tolman KG, Chandramouli J. Hepatotoxicity of the thiazolidinediones. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:369-79, vi.

36. Khan RS, Bril F, Cusi K, Newsome PN. Modulation of insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2019;70:711-24.

37. Wu L, Li Z, Gao N, et al. Interferon-α could induce liver steatosis to promote HBsAg loss by increasing triglyceride level. Heliyon. 2024;10:e32730.

38. Sørensen P, Edal AL, Madsen EL, Fenger C, Poulsen MR, Petersen OF. Reversible hepatic steatosis in patients treated with interferon alfa-2A and 5-fluorouracil. Cancer. 1995;75:2592-6.

39. Choudhari P, Patni N. Updates in the management of pediatric dyslipidemia. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2023;34:156-61.

40. Kumar N, Kalaiselvan V, Arora MK. Neuronal toxicity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): an analysis of post-marketing reports from FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) safety database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2024;80:1685-95.

41. Kaplowitz N, Aw TY, Simon FR, Stolz A. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:826-39.

42. Kral JG, Schaffner F, Pierson RN Jr, Wang J. Body fat topography as an independent predictor of fatty liver. Metabolism. 1993;42:548-51.

44. Tran K, McCormack S. Exercise for the treatment of ankle sprain: a review of clinical effectiveness and guidelines. 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563007/. [Last accessed on 24 Oct 2025].

45. Niederberger E, Kuner R, Geißlinger G. Pharmacological aspects of pain research in Germany. Schmerz. 2015;29:531-8. (in German).

46. Te H, Doucette K. Viral hepatitis: guidelines by the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Disease Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13514.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.