Neurochemical memory diversification towards liquid reinforcement learning

Abstract

The creation of biological memory analogs has long been hindered by the fundamental mechanistic differences between solid-state electronics and biological systems. By manipulating biomolecules in appropriate electrolytic environments, aqueous emulation of memory and its diversification has recently emerged. Here, we present real neurochemical memory diversification based on a nascent organic photoelectrochemical transistor and its implementation toward liquid reinforcement learning (RL). By employing neurochemicals H2S and H2O2 as reward and clearance signals, respectively, the device demonstrates reversible switching between strengthened and suppressed memory, reproducing diversified memory behaviors analogous to those in the human brain. As its diversified memory supports adaptive decision-making and strategy updating, it is further applied to a navigation task for efficient RL. This work provides a strategy for aqueous neurochemical memory diversification and highlights liquid-phase RL for advanced neuromorphic applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Memory is one of the most important physiological functions of the human brain wherein information is encoded, stored and retrieved[1-3]. Inspired by this, artificial memory devices have been increasingly pursued in neuromorphic engineering toward advanced artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things[4-6]. As very recently summarized by Samorì et al., memory diversification has been actively pursued in various solid-state electronics via a plethora of optical, electrical, electrochemical, magnetic, and mechanical means[7]. Nevertheless, the operating principles of these solid-state devices are fundamentally distinct from those of the human brain, which relies on intricate physicochemical processes within an electrolytic environment[8]. More essentially, the human brain employs different neurochemicals to regulate memory kinetics[7,9]. his emphasizes that neurochemicals play pivotal roles in memory and signifies that truly biomimetic memory should be neurochemically diversifiable.

Aqueous neuromorphic techniques - the innovation of devices that speak chemical language in electrolytes - are currently experiencing substantial growth in research[10-12], driven by their potential to streamline the interface between artificial and biological systems. Among them, nanofluidic memristors[13-18] and organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs)[19-28] have been particularly explored. In terms of memory behaviors, enhanced memory has been achieved through slow ion transport in nanofluidic memristors[14] and large migrating ions in OECTs[29,30]. Nevertheless, neurochemical memory diversification remains challenging. To explore the biochemical events that modulate conductance, we previously proposed an organic photoelectrochemical transistor (OPECT) that links the realms of photoelectrochemistry[31-34] and OECTs. As it can perceive light-biochemical signals through parallel transmission of ions and molecules in electrolytes, this nascent technique has rapidly stood out as a promising approach to aqueous neuromorphic exploration[35-41].

By neurochemical mediation, reward-induced memory serves as a crucial basis for reward circuitry supporting advanced learning and decision-making in the human brain[42-44]. Inspired by such neurochemical reward mechanisms, reinforcement learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful machine learning paradigm. RL algorithms use reward-driven feedback to optimize decision-making strategies, mirroring the adaptive learning process of the brain[45-54]. To implement RL neural networks, synaptic weights are commonly adjusted through correlations between timing and reward signals[52]. In this process, diversified memory is indispensable, as it supports reward-induced updating and maintenance of device conductance[48-50]. For instance, Sarwat et al. used the combined effects of light and electrical stimuli to tune memory for RL in a solid-state chalcogenide optomemristor[46]. Despite this progress, aqueous implementation of RL, especially that mediated by real neurochemicals, remains unexplored. Here, we report neurochemical memory diversification on OPECTs toward RL in aqueous media.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), CdCl2·xH2O, and Na2S·9H2O were obtained from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The compound 2-methylimidazole (2-MI) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Zn(NO3)2·6H2O was purchased from Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shantou, China). A poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) dispersion (Clevios PH1000) was obtained from Heraeus Ltd. (Hanau, Germany).

Fabrication of Cd2+/ZnO electrode

PVP (0.2 g) was dissolved in 40 mL of deionized water under magnetic stirring. Subsequently, 4 mL of an aqueous solution containing 0.6568 g of 2-MI was introduced into the PVP solution under continuous stirring, followed by the dropwise addition of 4 mL of an aqueous solution of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.238 g). After complete dissolution, the mixture was kept undisturbed for 24 h. The resulting precipitate was washed three times with deionized water and ethanol, respectively, and dried at 60 °C to yield zeolitic imidazolate framework-L (ZIF-L). The obtained ZIF-L was then calcined in a muffle furnace: first heated to 350 °C at 2 °C·min-1 and maintained for 60 min, then increased to 450 °C at 1 °C·min-1 and maintained for 30 min, affording ZIF-L-derived ZnO. Next, ZnO was dispersed in deionized water to form a suspension (2 mg·mL-1), which was drop-cast onto indium tin oxide (ITO) substrates and dried at 60 °C. The ZnO/ITO electrodes were then immersed in a 10 mM CdCl2·xH2O aqueous solution for 30 min and dried at 37 °C for 30 min to obtain the Cd2+/ZnO electrode.

H2S and H2O2 treatment

In a 5 mL centrifuge tube, 2 mL of a Na2S·9H2O solution at a specified concentration was prepared, and the Cd2+/ZnO electrode obtained was immersed in it for 1 h. The electrode was then rinsed with deionized water to remove residual ions, followed by drying at 37 °C for 30 min to obtain the CdS/ZnO electrode. On the other hand, to etch the CdS, a mixed solution of horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 1 mg/mL) and H2O2 at a specified concentration was prepared and thoroughly mixed. A volume of 25 μL of this solution was dropped onto the CdS/ZnO electrode, followed by incubation at room temperature for 15 min, rinsing with water, and drying at 37 °C for 30 min.

Fabrication of polymeric channel[38]

First, a 10 nm Cr layer and a 100 nm Au layer were deposited onto a glass substrate covered by a shadow mask. The length and width of the channel were 6 mm and 0.2 mm, respectively. Subsequently, 0.1 mL of PEDOT:PSS dispersion containing 5% (v/v) dimethyl sulfoxide was dropped onto the substrate, spin-coated at 4,000 rpm for 30 s, and annealed at 180 °C for 1 h.

Device characterization

The electrical signals were recorded using a photoelectrochemical/organic transistor detector (Nandaguang, Nanjing, China) in the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) electrolyte. The channel voltage was set to 0.1 V during testing.

Design of the RL algorithm

To implement RL for the navigation task, we used a simple weight-update rule based on the device’s response to neurochemical inputs. The postsynaptic current response (ΔPSC) was modeled as a function of pulse number, derived from experimental measurements under repeated light pulses. The long-term (ltm) and short-term (stm) components of ΔPSC were expressed as:

where current_ep is the postsynaptic current measured at the ep-th light pulse, and the constants are fitting parameters obtained from experimental data. These functions describe how the synaptic conductance evolves with the number of presynaptic spikes (simulated by light pulses) under the influence of H2S (reward) or H2O2 (clearance).

The function was then used for training in MATLAB (MATrix LABoratory). Whenever the rodent reached the endpoint, the reward signal (H2S) was applied, and the synaptic weights corresponding to the taken path were updated according to the fitted reward-response curve. Conversely, when the reward was cleared (H2O2), the weights were updated using the clearance-response curve. This approach allowed the synaptic connections to be strengthened for rewarded paths and weakened for non-rewarded or erroneous ones, enabling the network to progressively learn the optimal route.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

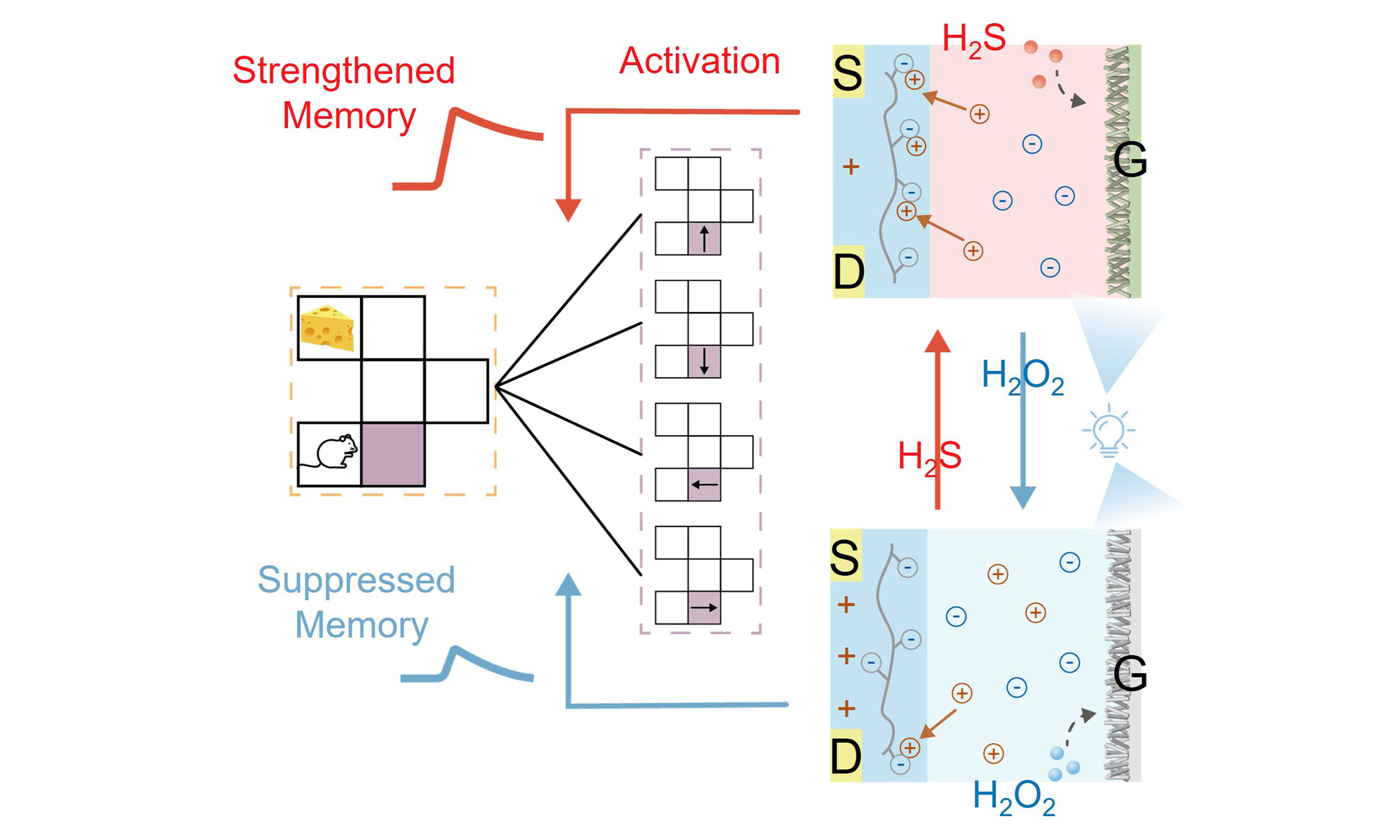

Design of theneurochemical-mediated RL

Figure 1A demonstrates the typical mechanism of reward-induced memory in the human brain. Specifically, in neural circuits, neurochemical stimuli act as reward signals that modulate synaptic plasticity in brain regions governing reward processing, thereby strengthening functional connections between specific neural pathways, underlying the induction of strengthened memory at these synapses[55]. This activity-dependent enhancement of neuronal communication enables the brain to encode reward-associated experiences, establishing a biological basis for how neurochemical inputs facilitate the learning and memory consolidation of rewarding behaviors. Down to the synaptic level, as shown in Figure 1B, such diversified memory dynamics are achieved by specific neurochemicals. Typically, the hydrogen sulfide (H2S), as a well-known neurochemical, can lead to the inward flow of ions to induce strengthened memory[56]. On the other hand, reactive oxygen species (ROS), e.g., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), can inhibit H2S activity and thus reduce ion influx, thereby suppressing memory[57].

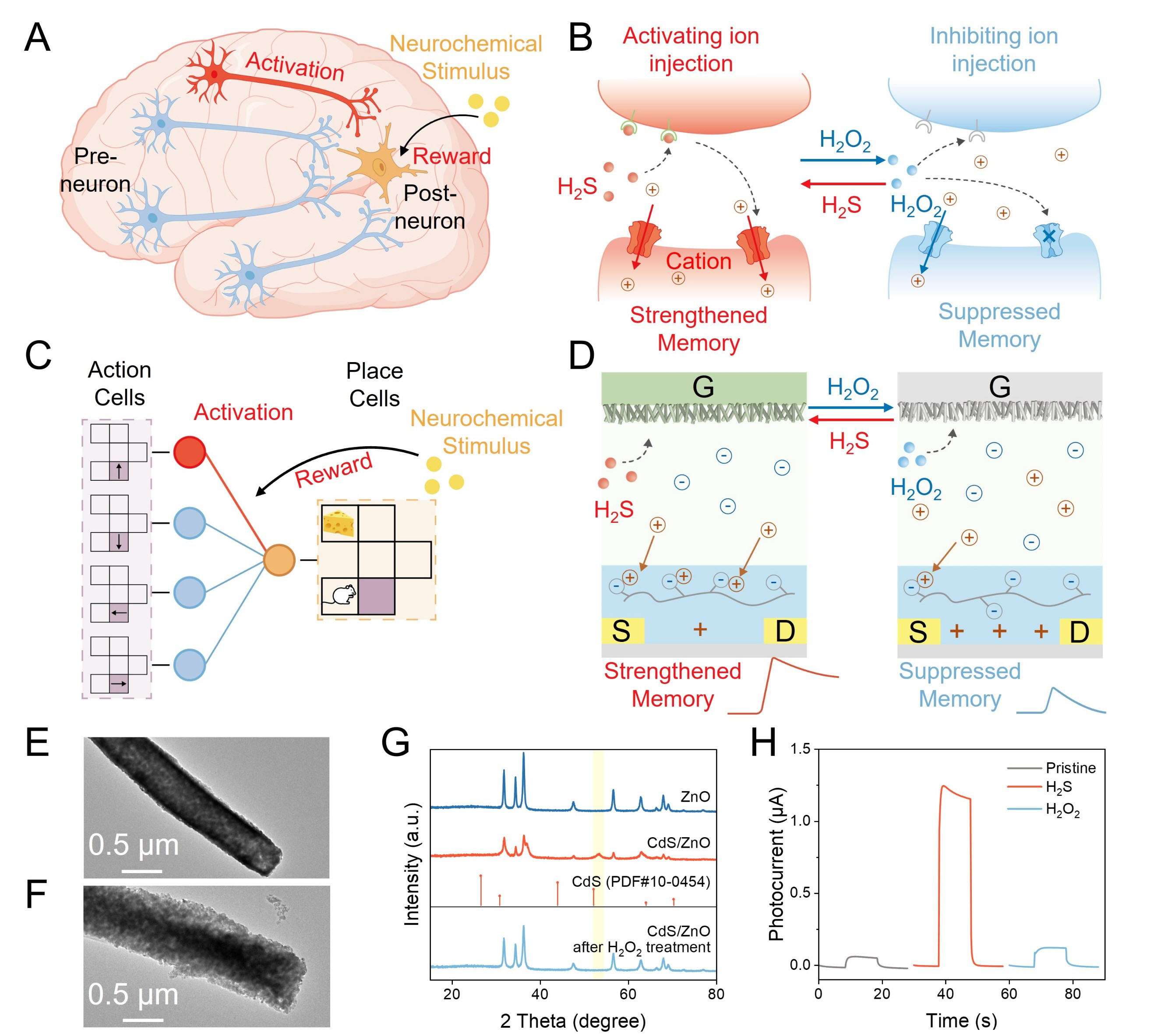

Figure 1. (A) Schematic illustration of reward learning in the human brain; (B) Schematic illustration of the biological strengthened memory and suppressed memory at the synaptic level; (C) Schematic illustration of the RL neural network diagram for navigation; (D) Schematic of the biological memory diversification of the device. TEM images of (E) ZnO and (F) CdS/ZnO; (G) XRD spectra of ZnO (blue curve), CdS/ZnO (red curve), and CdS/ZnO after H2O2 treatment (light blue curve); (H) Photocurrent responses of pristine electrode, H2S-treated electrode, and H2O2-treated electrode. PDF: Powder Diffraction Powder; RL: reinforcement learning; XRD: X-ray diffraction; TEM: transmission electron microscopy.

Taking this inspiration, an artificial neural network with RL was designed for a navigation application. As shown in Figure 1C, it consisted of presynaptic neurons encoding movement directions and postsynaptic neurons encoding positions, linked by artificial synapses. Analogous to that in the human brain, a real neurochemical stimulus was introduced as a reward signal to tune memory and thus update synaptic weights. Specifically, as shown in Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 1, an OPECT synapse with memory diversification was developed, in which the PEDOT:PSS channel was modulated by a Cd2+/ZnO photogate in aqueous media. The addition of H2S as the reward, would enhance photo-induced voltage, driving more cations into the channel and thus strengthening memory. By contrast, the addition of H2O2 would reduce the clearance of CdS, leading to lower photo-induced voltage, inhibiting cation injection into the channel, and thus suppressing memory. Such a neurochemically dependent memory can be implemented to adjust the conductivity for updating synaptic weights in the RL neural network.

The successful fabrication of the device was characterized as shown in Supplementary Figures 2-5. As presented in Figure 1E and F, the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images revealed that after the treatment of H2S, many particles were generated on the surface of ZnO, which were confirmed as CdS by corresponding energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mapping, as shown in Supplementary Figure 6. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra in Supplementary Figure 7 also validated the formation of CdS. In addition, as shown in Figure 1G, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra exhibited an extra characteristic peak of CdS after the treatment of H2S, which disappeared after H2O2 treatment, indicating the reversible generation and clearance of CdS. The corresponding photoelectrochemical characteristics were further studied using a conventional three-electrode system. As shown in Figure 1H, the pristine Cd2+/ZnO photogate exhibited a photocurrent of ca. 0.06 μA, while the treatment of H2S caused a substantially enhanced photocurrent of ca. 1.2 μA. After further H2O2 treatment, the photocurrent returned to ca. 0.12 μA. Such phenomena could be explained by the mechanism illustrated in Supplementary Figure 8, which is further supported by the light-absorption results shown in Supplementary Figure 9.

Neurochemical-mediated diversified memory

Figure 2A presents the ∆PSC of the OPECT device before and after the treatment of H2S and H2O2. As shown, after H2S treatment, the device exhibited substantially increased ∆PSC and slower return to the initial level. By contrast, after subsequent treatment with H2O2, the ∆PSC decreased with a faster decay, which, nevertheless, was still higher than that of the pristine photogate due to the residual CdS. To evaluate variation in memory behavior, the memory time (defined as the time required for the ∆PSC to decay to 1% of its peak value) was investigated by calculating the extrapolated horizontal of the decay curves. As shown in Figure 2B, compared to the 230 s memory time of the pristine device, the memory time after H2S treatment exceeded 40,000 s, indicating the significantly enhanced memory behavior. Furthermore, a comparative analysis with other reported optoelectronic synaptic devices was performed, as summarized in Supplementary Table 1, which revealed that the memory performance of this device was markedly superior to that of previously reported systems. The treatment with H2O2 would result in a decreased memory time of ca. 300 s, indicating the adjustable memory behavior.

Figure 2. All light used was 2 s 15.17 mW·cm–2. (A) ΔPSC responses and (B) the decay of the pristine device and that after the treatment of H2S and subsequent H2O2; (C) Mechanism of diversified memory dynamics from the perspective of electron transfer. ΔPSC responses after the treatment of (D1) H2S and (D2) H2O2 with different concentrations; Variations of τ and ΔPSC with the increased (E1) H2S and (E2) H2O2 concentrations; Recyclability of (F) ΔPSC and (G) τ upon alternating H2S and H2O2 treatments. ΔPSC: Postsynaptic current response; H2S: hydrogen sulfide; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; ITO: indium tin oxide; CB: conduction band; VB: valence band.

The mechanism of such a phenomenon could be attributed to altered electron-transfer dynamics. As shown in Figure 2C, the presence of H2S resulted in the formation of CdS/ZnO Z-scheme heterojunction[58]. Upon light illumination, the photo-excited electrons on the conduction band (CB) of CdS would transfer to the valence band (VB) of ZnO, and the photo-excited electrons on the CB of ZnO would transfer to the substrate electrode, producing a photo-induced voltage. Under light illumination, the residual electrons on the CB of ZnO and holes on the VB of CdS were difficult to recombine due to the bending of energy bands, leading to slow decay of the photo-induced voltage and thus the generation of strengthened memory. On the other hand, the treatment of H2O2 would result in the clearance of CdS. Upon light illumination, the as-treated device could generate a much lower photo-induced voltage, leading to a decreased ∆PSC. Under light illumination, rapid electron-hole recombination led to a faster decay of the photo-induced voltage and thus to suppressed memory. This phenomenon was further corroborated by the open-circuit potential (OCP) and electrical pulse response results, as shown in Supplementary Figures 10 and 11.

The relationship between neurochemical concentrations and memory behaviors was then studied. As shown in Figure 2D1, with increased H2S concentrations, the device exhibited gradually increased ∆PSC due to the increased production of CdS. Conversely, as shown in Figure 2D2, increasing H2O2 concentrations would result in a decreased ∆PSC, due to greater heterojunction destruction. As shown in Figure 2E1 and E2, the as-calculated characteristic decay time τ (defined as the time required for current to decay from the peak to 1/e of the peak value) increased with increasing H2S concentration and decreased with increasing H2O2 concentration, indicating improved and suppressed memory, respectively. Such results were highly analogous to the H2S and H2O2-mediated memory and forgetting in the human brain[56,57]. Moreover, as shown in Figure 2F and G, both the ∆PSC and τ values exhibited reversible and reproducible changes upon three cycles of H2S and H2O2 treatments, confirming the recyclable memory behavior. In addition, the effects of varying ionic strength, pH, oxygen concentration, and different interfering species on device performance were systematically investigated, as shown in Supplementary Figure 12, further demonstrating the specificity and stability of the device.

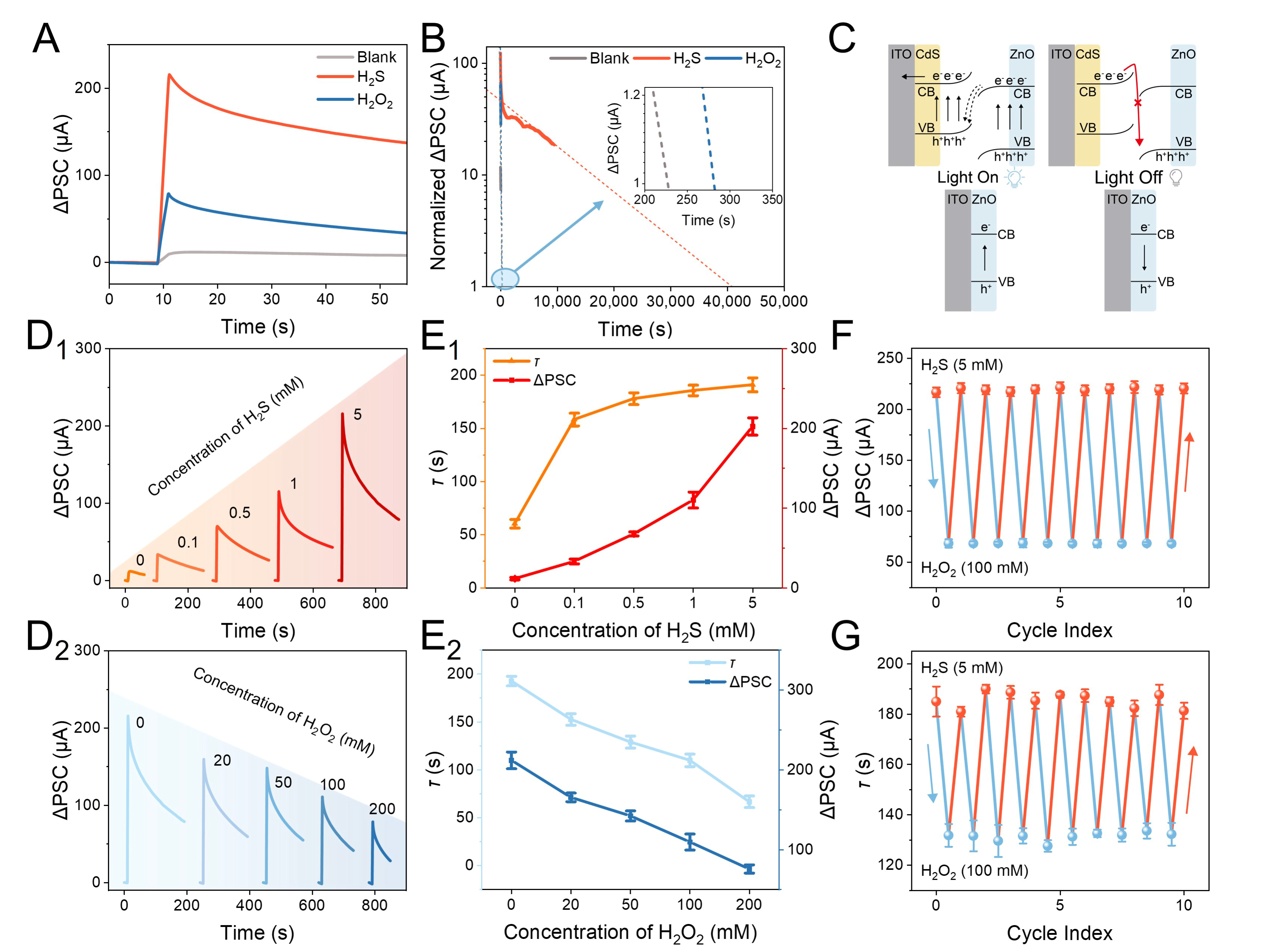

Neurochemical-mediated synaptic plasticity

In the human brain, synaptic plasticity represents a fundamental function underlying memory and learning[59]. In the reward circuitry, synaptic plasticity is mediated by neurochemical reward signals, inducing widespread alterations in the neural network[60]. Here, neurochemical-mediated short-term plasticity was initially emulated by applying two light pulses with the treatments H2S and H2O2, respectively. As shown in Figure 3A1 and A2, the ΔPSC exhibited typical paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) behavior. Notably, compared to that of the pristine device, the addition of H2S resulted in both enhanced ΔPSC value, improved PPF index (I2/I1), and slower decay of the PPF index with increased interval (∆t), emulating the reward-mediated strengthened memory, which was further inhibited by the addition of H2O2.

Figure 3. PPF behaviors of (A1) the pristine devices, and those after the treatment of H2S, and (A2) the pristine devices, and those after the treatment of H2O2; The inset shows the PPF indices for different pulse intervals (1 s, 15.17 mW·cm-2 light pulses). SIDP emulation of the device after the treatment of (B1) H2S and (B2) H2O2 with light intensities ranging from 2.013 mW·cm-2 to 82.38 mW·cm-2 (1 s light pulses); SDDP emulation of the device after treatment of (C1) H2S and (C2) H2O2 with pulse durations ranging from 0.5 s to 8 s (15.17 mW·cm-2 light pulses); SNDP emulation of the device after treatment of (D1) H2S and (D2) H2O2 with 2 to 10 pulses (15.17 mW·cm-2 light pulses); SRDP emulation of the device after treatment of (E1) H2S and (E2) H2O2 with light pulse intervals ranging from 10 s to 2 s (1 s, 15.17 mW·cm-2 light pulses); (F1) H2S-mediated synaptic plasticity; (F2) H2O2-mediated synaptic plasticity (1 s, 15.17 mW·cm-2 light pulses). ΔPSC: Postsynaptic current response; PPF: paired-pulse facilitation; H2S: hydrogen sulfide; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; SIDP: spike-intensity-dependent plasticity; SDDP: spike-duration-dependent plasticity; SNDP: spike-number-dependent plasticity; SRDP: spike-rate-dependent plasticity.

Spike-dependent plasticity represents another significant plasticity demonstrating the relationship between synaptic weight and the characteristics of spikes, which was also studied by biochemical reward signals. As shown in Figure 3B1 and B2, higher light intensity caused ΔPSC to rise progressively and exhibit slower retention to the initial level, mimicking spike-intensity-dependent plasticity (SIDP). As shown in Figure 3C1 and C2, longer pulse duration also resulted in larger ΔPSC and slower retention, mimicking spike-duration-dependent plasticity (SDDP). Moreover, as shown in Figure 3D and E, increasing the pulse number and shortening the pulse interval led to enhanced ΔPSC, emulating spike-number-dependent plasticity (SNDP) and spike-rate-dependent plasticity (SRDP), respectively. Significantly, with the addition of H2S, the ΔPSC exhibited enhanced variation with changed pulse characteristics and the retention time substantially improved as compared to that of H2O2, which was highly analogous to the reward-mediated plasticity in biology[54,55]. Significantly, the relationship between the concentrations of neurochemicals and synaptic plasticity was studied. As shown in Figure 3F1 and F2, increased H2S concentration resulted in enhanced ΔPSC and memory, while increased H2O2 concentration led to suppressed ΔPSC and memory, which was analogous to that in biology.

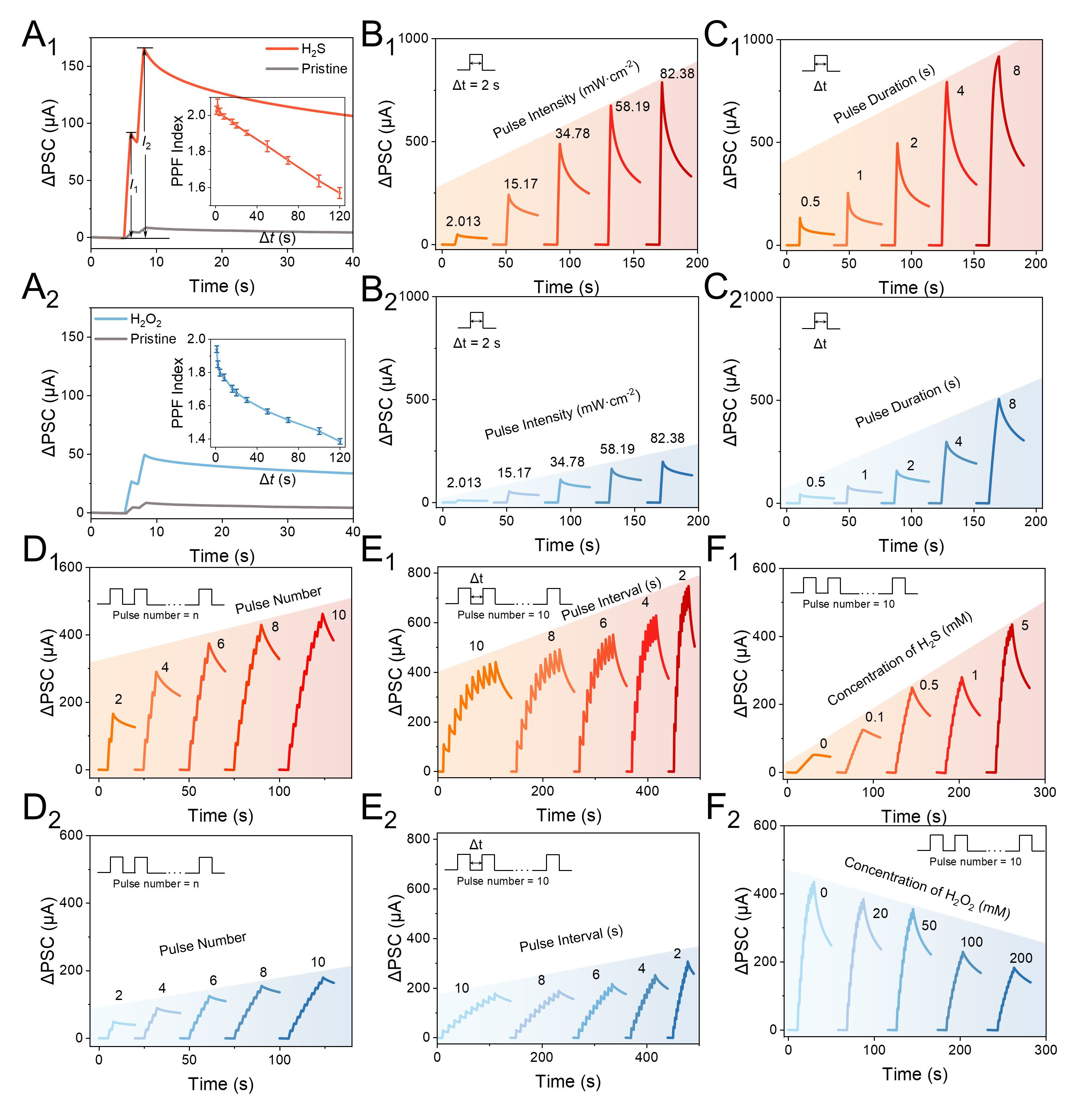

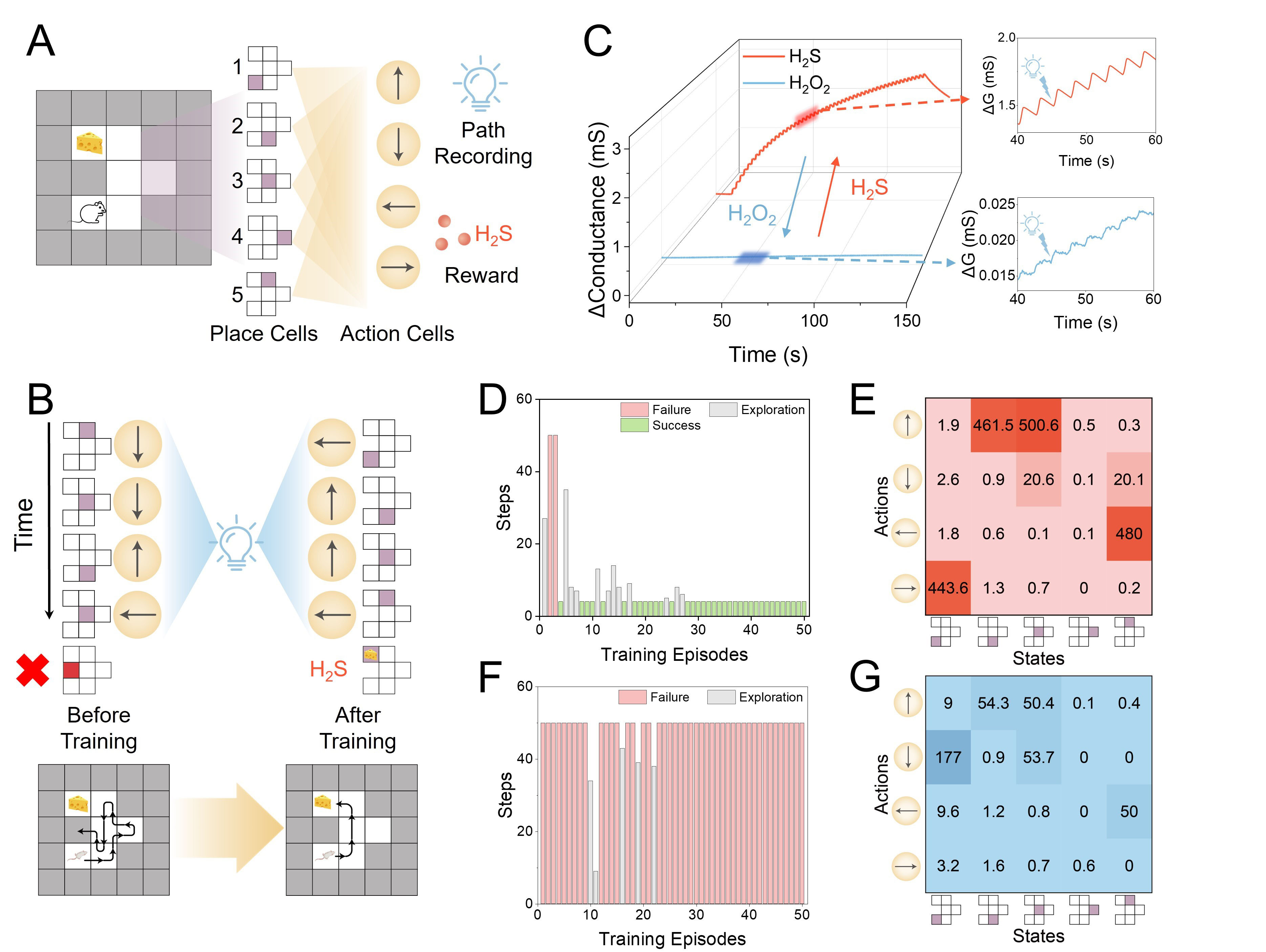

Emulation of the RL

Navigation is a standard task to investigate the performance of RL and the corresponding hardware designs[46,61]. Principally, the feedback signals will induce strengthened/suppressed memory to strengthen/suppress the synaptic connection between specific locations and action neurons, resulting in the habitual action at the corresponding location. Here, we present an example game: a rodent trapped in a maze to search for cheese and avoid obstacles. Specifically, as shown in Figure 4A, the maze consisted of 6 positions (white blocks), including a starting point and an endpoint, and a surrounding circle of walls (black blocks). The rodent had 4 possible directions of motion at these positions. Therefore, a 5 × 4 neural network was constructed to determine the movement at each position, with the device conductance serving as synaptic weights, representing the probability of each direction. Light pulses were applied to emulate the presynaptic spikes that record the traversed paths. Each pulse triggered a photoresponse in the OPECT synapse, modulating channel conductance and hence the synaptic weight associated with that movement direction. As the rodent explored the maze, different paths generated different sequences of light pulses, corresponding to the activation of specific position-direction synapses, inducing variation of synaptic weights linking corresponding positions and directions. H2S and H2O2 served as reward signals and reward clearance, respectively. The specific training process of RL was illustrated in Figure 4B. As shown, before training, the rodent engaged in random exploration of the maze. If it failed to reach the endpoint after 50 steps or collided with a wall, it was returned to the starting point. Once the rodent successfully reached the endpoint, the H2S reward signal was applied, strengthening memory and updating the synaptic weights of the traversed paths. It was then returned to the starting point for the next training epoch, and H2O2 cleared the reward, recovering the suppressed memory. After reinforcement learning, the rodent was able to find the shortest path to the endpoint.

Figure 4. (A) Schematic of a rodent navigation task; (B) Training process of the navigation; (C) Device responses under 50 continuous light pulses after the treatment of H2S (red curve) and H2O2 (blue curve) (2 s, 15.17 mW·cm-2 light pulses); (D) Exploration result with increased training epochs with the assistance of a reward; (E) Synaptic weights matrix after training with the assistance of a reward; (F) Exploration result with increased training epochs without the assistance of a reward; (G) Synaptic weights matrix after training without the assistance of a reward. H2S: Hydrogen sulfide; H2O2: hydrogen peroxide; ΔG: ΔConductance.

Such a process was then experimentally realized by H2S- and H2O2-mediated memory. As shown in Figure 4C, the addition of H2S resulted in a substantially enhanced Δconductance (red curve), while the addition of H2O2 caused a much-suppressed Δconductance with increased light pulse number (blue curve). Moreover, as shown in Supplementary Figure 13, the conductance window and the nonlinearity were measured, revealing that the H2S-treated device was suitable for RL. As shown in Figure 4D, with the assistance of a reward, the rodent found the shortest path after four training trials and continued to choose it after 27 training trials. Repeated tests, shown in Supplementary Figure 14, all yielded similarly successful outcomes. As shown in Figure 4E, the synaptic weights corresponding to the shortest path (position 1 moves right, positions 2 and 3 move upward, and position 5 moves left) were substantially enhanced, indicating successful training. By contrast, as shown in Figure 4F, without the reward, the rodent reached the endpoint only five times, and the shortest path was not identified. As shown in Figure 4G, the synaptic weights corresponding to the wrong path (positions 1 and 3 move downward) were enhanced. These results indicate the capability of RL to improve training efficiency. If the reward function was replaced with a stochastic reward function, the training process, as shown in Supplementary Figure 15A, was dominated by maze exploration for the majority of trials. In addition, when the reward function was set to a constant value (e.g., 10), the rodent more frequently identified the shortest path, as shown in Supplementary Figure 15B. Moreover, we extended the proposed method to a larger 4 × 5 maze, as shown in Supplementary Figure 16, and the results demonstrated that the shortest path could still be successfully identified.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this work establishes a new paradigm for neurochemical memory diversification on OPECT towards liquid-phase RL, in which H2S and H2O2 serve as reward and clearance signals to reversibly regulate memory states. Beyond reproducing fundamental synaptic plasticity such as PPF and spike-dependent plasticity, it enables dynamic modulation of device conductance and, consequently, diversified memory behaviors. Importantly, by implementing these neurochemical-regulated functions in a navigation task, we verify the capability of neurochemical memory diversification to support efficient RL in aqueous media. To the best of our knowledge, this study demonstrates the first neurochemical memory diversification in an organic transistor operating in liquid, and we anticipate that this approach will inspire higher-level biological memory analogs for neuromorphic applications.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study and performed data analysis and interpretation: Lou, H.; Yuan, C.

Performed data acquisition: Zhu, Y. C.; Chen, F. Z.; Jia, H. M.

Provided administrative, technical, and material support: Xu, J. J.; Zhao, W. W.

Lou, H.; Yuan, C. contributed equally to this work.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22174063 and 22374066) and the Excellent Research Program of Nanjing University (ZYJH004).

Conflicts of interest

Zhao, W. W. is an Editorial Board Member of the journal Iontronics but is not involved in any steps of the editorial process, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making, while the other authors declared that there have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Dudai, Y.; Karni, A.; Born, J. The consolidation and transformation of memory. Neuron 2015, 88, 20-32.

3. Josselyn, S. A.; Tonegawa, S. Memory engrams: recalling the past and imagining the future. Science 2020, 367.

4. Zidan, M. A.; Strachan, J. P.; Lu, W. D. The future of electronics based on memristive systems. Nat. Electron. 2018, 1, 22-9.

5. Li, C.; Belkin, D.; Li, Y.; et al. Efficient and self-adaptive in-situ learning in multilayer memristor neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2385.

6. Zhong, Y.; Tang, J.; Li, X.; Gao, B.; Qian, H.; Wu, H. Dynamic memristor-based reservoir computing for high-efficiency temporal signal processing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 408.

7. Chen, Y.; Han, B.; Gobbi, M.; Hou, L.; Samorì, P. Responsive molecules for organic neuromorphic devices: harnessing memory diversification. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2418281.

8. Titley, H. K.; Brunel, N.; Hansel, C. Toward a neurocentric view of learning. Neuron 2017, 95, 19-32.

9. Magistretti, P. J.; Allaman, I. Lactate in the brain: from metabolic end-product to signalling molecule. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 235-49.

10. He, K.; Wang, C.; He, Y.; Su, J.; Chen, X. Artificial neuron devices. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 13796-865.

11. Harikesh, P. C.; Tu, D.; Fabiano, S. Organic electrochemical neurons for neuromorphic perception. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 525-36.

12. Sung, M. J.; Kim, K. N.; Kim, C.; et al. Organic artificial nerves: neuromorphic robotics and bioelectronics. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 2625-64.

13. Xiong, T.; Li, C.; He, X.; et al. Neuromorphic functions with a polyelectrolyte-confined fluidic memristor. Science 2023, 379, 156-61.

14. Robin, P.; Emmerich, T.; Ismail, A.; et al. Long-term memory and synapse-like dynamics in two-dimensional nanofluidic channels. Science 2023, 379, 161-7.

15. Emmerich, T.; Teng, Y.; Ronceray, N.; et al. Nanofluidic logic with mechano-ionic memristive switches. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 271-8.

16. Xiao, Y.; Sun, W.; Gao, C.; et al. Neural functions enabled by a polarity-switchable nanofluidic memristor. Nano. Lett. 2024, 24, 12515-21.

17. Song, R.; Wang, P.; Zeng, H.; et al. Nanofluidic memristive transition and synaptic emulation in atomically thin pores. Nano. Lett. 2025, 25, 5646-55.

18. Wang, Y.; Jian, B.; Ling, Y.; et al. Bioinspired nanofluidic circuits with integrating excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Nano. Lett. 2025, 25, 2298-306.

19. Chen, X.; Marks, A.; Paulsen, B. D.; et al. n-type rigid semiconducting polymers bearing oligo(ethylene glycol) side chains for high-performance organic electrochemical transistors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 9368-73.

20. Harikesh, P. C.; Yang, C. Y.; Wu, H. Y.; et al. Ion-tunable antiambipolarity in mixed ion-electron conducting polymers enables biorealistic organic electrochemical neurons. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 242-8.

21. Huang, W.; Chen, J.; Yao, Y.; et al. Vertical organic electrochemical transistors for complementary circuits. Nature 2023, 613, 496-502.

22. Song, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; et al. 2D metal-organic frameworks for ultraflexible electrochemical transistors with high transconductance and fast response speeds. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd9627.

23. Cucchi, M.; Parker, D.; Stavrinidou, E.; Gkoupidenis, P.; Kleemann, H. In liquido computation with electrochemical transistors and mixed conductors for intelligent bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2209516.

24. Ding, B.; Kim, G.; Kim, Y.; et al. Influence of backbone curvature on the organic electrochemical transistor performance of glycolated donor-acceptor conjugated polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19679-84.

25. Laswick, Z.; Wu, X.; Surendran, A.; et al. Tunable anti-ambipolar vertical bilayer organic electrochemical transistor enable neuromorphic retinal pathway. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6309.

26. Lobosco, A.; Lubrano, C.; Rana, D.; et al. Enzyme-mediated organic neurohybrid synapses. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2409614.

27. Matrone, G. M.; van Doremaele, E. R. W.; Surendran, A.; et al. A modular organic neuromorphic spiking circuit for retina-inspired sensory coding and neurotransmitter-mediated neural pathways. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2868.

28. Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; et al. A high-frequency artificial nerve based on homogeneously integrated organic electrochemical transistors. Nat. Electron. 2025, 8, 254-66.

29. Liu, X.; Dai, S.; Zhao, W.; et al. All-photolithography fabrication of ion-gated flexible organic transistor array for multimode neuromorphic computing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2312473.

30. Liu, R.; He, Y.; Zhu, X.; et al. Hardware-feasible and efficient n-type organic neuromorphic signal recognition via reservoir computing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2409258.

31. Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Kirlikovali, K. O.; et al. Ultrafine silver nanoparticle encapsulated porous molecular traps for discriminative photoelectrochemical detection of mustard gas simulants by synergistic size-exclusion and site-specific recognition. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2202287.

32. Huang, H.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; et al. Photoelectrochemical lithium extraction. Nano. Energy. 2023, 115, 108683.

33. Huang, C.; Xiong, P.; Lai, X.; Xu, H. Photoelectrochemical asymmetric catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 1250-4.

34. Gu, S.; Xu, D.; Huang, J.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Photoelectrochemical biosensor with single atom sites for norepinephrine sensing and brain region synergy in epilepsy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4765.

35. Corrado, F.; Bruno, U.; Prato, M.; et al. Azobenzene-based optoelectronic transistors for neurohybrid building blocks. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6760.

36. Druet, V.; Ohayon, D.; Petoukhoff, C. E.; et al. A single n-type semiconducting polymer-based photo-electrochemical transistor. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5481.

37. Li, Z.; Chen, M. H.; Wu, Q. Q.; et al. A metal-organic framework neuron. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2025, 12, nwaf213.

38. Yuan, C.; Xu, K. X.; Huang, Y. T.; Xu, J. J.; Zhao, W. W. An aquatic autonomic nervous system. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2407654.

39. Gao, C.; Liu, D.; Xu, C.; et al. Feedforward photoadaptive organic neuromorphic transistor with mixed‐weight plasticity for augmenting perception. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313217.

40. Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, X.; et al. Low-power and multimodal organic photoelectric synaptic transistors modulated by photoisomerization for UV damage perception and artificial visual recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2420073.

41. Wang, Y.; Shan, W.; Li, H.; et al. An optoelectrochemical synapse based on a single-component n-type mixed conductor. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1615.

42. Braun, E. K.; Wimmer, G. E.; Shohamy, D. Retroactive and graded prioritization of memory by reward. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4886.

43. Pedamonti, D.; Mohinta, S.; Dimitrov, M. V.; Malagon-Vina, H.; Ciocchi, S.; Costa, R. P. Hippocampus supports multi-task reinforcement learning under partial observability. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9619.

44. Golden, C. E. M.; Martin, A. C.; Kaur, D.; et al. Estrogen modulates reward prediction errors and reinforcement learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 2502-14.

45. Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529-33.

46. Sarwat, S. G.; Moraitis, T.; Wright, C. D.; Bhaskaran, H. Chalcogenide optomemristors for multi-factor neuromorphic computation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2247.

47. Romero Pinto, S.; Uchida, N. Tonic dopamine and biases in value learning linked through a biologically inspired reinforcement learning model. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7529.

48. Weilenmann, C.; Ziogas, A. N.; Zellweger, T.; et al. Single neuromorphic memristor closely emulates multiple synaptic mechanisms for energy efficient neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6898.

49. Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Song, W.; et al. Reinforcement learning with analogue memristor arrays. Nat. Electron. 2019, 2, 115-24.

50. Xia, Q.; Yang, J. J. Memristive crossbar arrays for brain-inspired computing. Nat. Mater. 2019, 18, 309-23.

51. Tomov, M. S.; Schulz, E.; Gershman, S. J. Multi-task reinforcement learning in humans. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 764-73.

52. Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhuge, F.; et al. A reconfigurable two-WSe2 -transistor synaptic cell for reinforcement learning. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2107754.

53. Li, Z.; Myers, S. K.; Xiao, J.; et al. Neuromorphic ionic computing in droplet interface synapses. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv6603.

54. Im, J.; Kim, J.; Ko, J.; et al. Hybrid functional 3D artificial synapses for convolution and reinforcement learning. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadw7498.

55. Kunz, L.; Staresina, B. P.; Reinacher, P. C.; et al. Ripple-locked coactivity of stimulus-specific neurons and human associative memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 587-99.

56. Wang, R. Physiological implications of hydrogen sulfide: a whiff exploration that blossomed. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 791-896.

57. Butterfield, D. A.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 148-60.

58. Wang, S.; Zhu, B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhou, M. Direct Z-scheme ZnO/CdS hierarchical photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic H2-production activity. Appl. Catal. B:. Environ. 2019, 243, 19-26.

59. Kandel, E. R. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science 2001, 294, 1030-8.

60. Mills, F.; Globa, A. K.; Liu, S.; et al. Cadherins mediate cocaine-induced synaptic plasticity and behavioral conditioning. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 540-9.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.