Interface-modulated deformability of liquid metal bridge

Abstract

Bridging liquid metal (LM) droplets embedded in composite matrices, such as elastomer polymers, are crucial for maintaining high conductivity and mechanical stretchability in flexible electronics. However, the deformability of these LM bridges under strain remains poorly understood. Here, we combine in situ transmission electron microscopy experiments with theoretical modeling to investigate the effects of interface modulation on LM bridge deformability. We find that strong interfacial wettability between LM nanodroplets and the solid substrate enhances stretchability, while the surface oxide layer of LM nanodroplets plays a more complex role. A thin oxide layer promotes symmetric liquid bridge formation, whereas a slight increase in thickness induces super-stretched liquid bridges. However, excessive oxide growth suppresses deformability by reducing LM liquidity. Accordingly, a strategy for controlling the deformation was developed by modulating the thickness of oxides through the regulation of stretching duration. This study reveals the kinetics of interface-driven liquid bridge deformation, providing fundamental insights for the precise engineering of stretchable LM-based conductors in next-generation flexible electronics.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Flexible electronics overcome the limitations of rigid devices by conforming to mechanical deformations while maintaining electrical functionality, enabling applications in sensors, wearable devices, and soft robotics[1-4]. However, achieving high stretchability without compromising conductivity remains a major challenge, primarily due to the lack of materials that combine high electrical conductivity with mechanical flexibility[5-7]. In contrast, liquid metal (LM)-based devices demonstrate a notable exception to Pouillet’s law, maintaining nearly constant resistance under tensile strain due to the inherent fluidity and adaptability of LM[8]. This distinctive property markedly enhances their suitability for advanced stretchable electronic applications[9-14]. Embedding LM nanodroplets within a polymer matrix has emerged as an effective strategy for fabricating stretchable, self-healing electronic circuits[15-17]. Conductive pathways within these composites are established through sintering processes, which enable the merging or interconnection of initially isolated LM particles. A variety of sintering techniques can be utilized to achieve this, including mechanical, thermal, laser, sonication, electrochemical, and chemical processing methods[18]. For example, Lee et al. demonstrated a hierarchical LM particle network via sonication sintering, where micrometer-sized particles (2-3 μm) provide structural support, while nanoscale particles (~100 nm) ensure conductivity[19]. This architecture enables stress dissipation while maintaining conductivity even at a 4,000% stretching rate.

A key factor in these LM-polymer composites is the formation and evolution of LM bridges, which yields conductivity under strain by providing continuous conductive pathways between adjacent droplets[20-23]. Their stability is governed by interfacial interactions, including solid-liquid adhesion at the substrate and liquid-gas interactions at the droplet surface[24-27]. If these liquid bridges rupture during deformation, circuit conductivity declines sharply. Thus, understanding the kinetics of liquid bridge deformation and developing strategies to regulate their stability are crucial for advancing high-performance, stretchable electronic systems with enhanced mechanical robustness and electrical reliability.

In this work, we studied the evolution dynamics of LM bridges formed between two LM nanodroplets through the combination of theoretical modeling and in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) characterizations. The theoretical model, incorporating both solid-liquid and liquid-gas interfacial effects, was validated through the mechanical analysis and direct TEM observations. Furthermore, we developed a strategy to modulate oxide thickness by controlling the stretching duration. These findings provide new insights into interface-driven deformation of LM nanodroplets (NDs) and establish a foundation for precisely engineered flexible electronics based on stretchable LM conductive bridges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Gallium nanodroplets were prepared by dispersing gallium in ethanol and subjecting the mixture to ultrasonication at 40 kHz with a power of 240 W for a total duration of 30 min. To prevent overheating and the potential formation of GaOOH nanorods, the ultrasonication was performed in an ice bath. Substrates were cut from metal sheets using precision metal scissors and subsequently sanded to eliminate edge imperfections caused by cutting, ensuring a smooth and uniform cross-section. Nanotips for indentation experiments were prepared from copper, molybdenum, zinc, and gold wires using electrochemical etching and focused ion beam (FIB) milling to achieve a flat tip area approximately

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

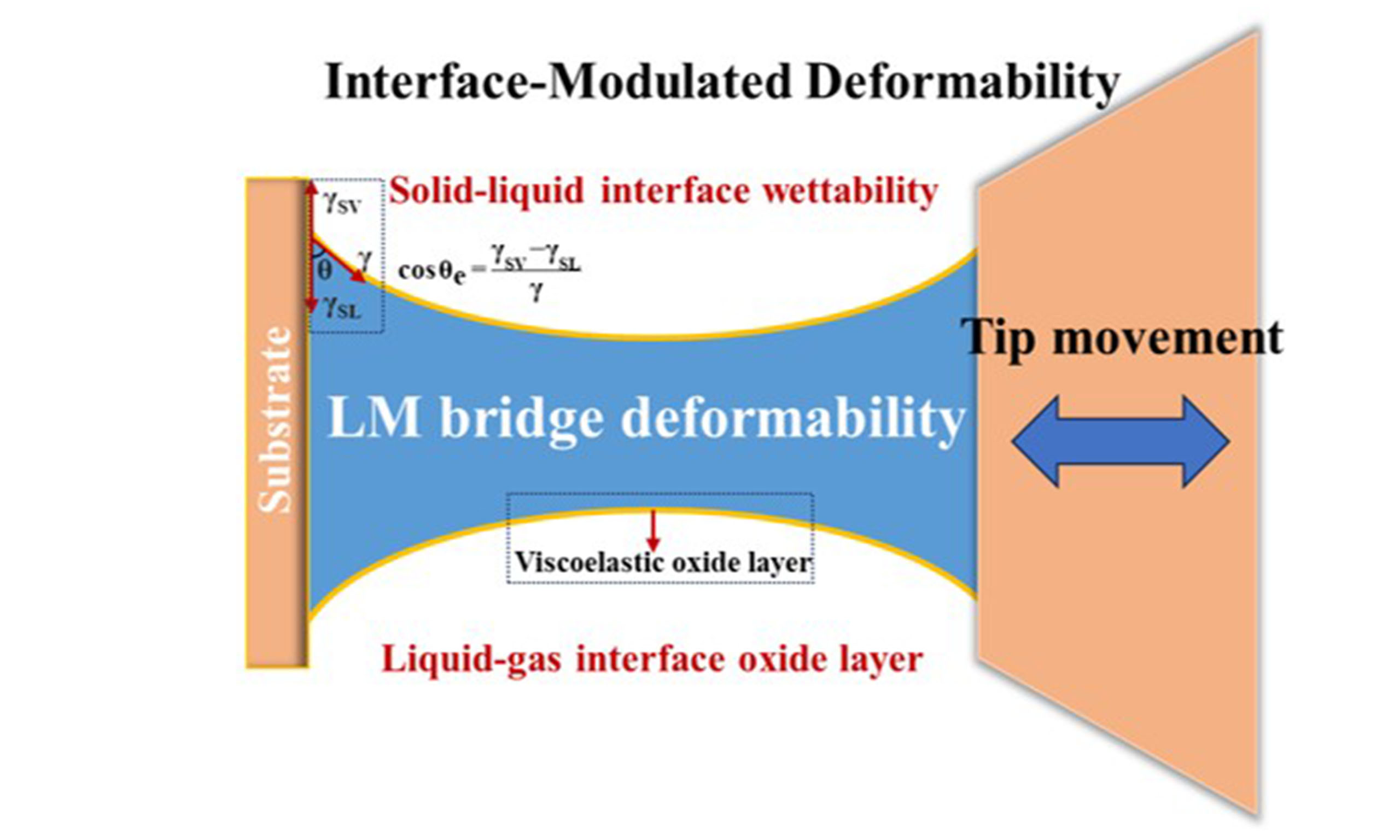

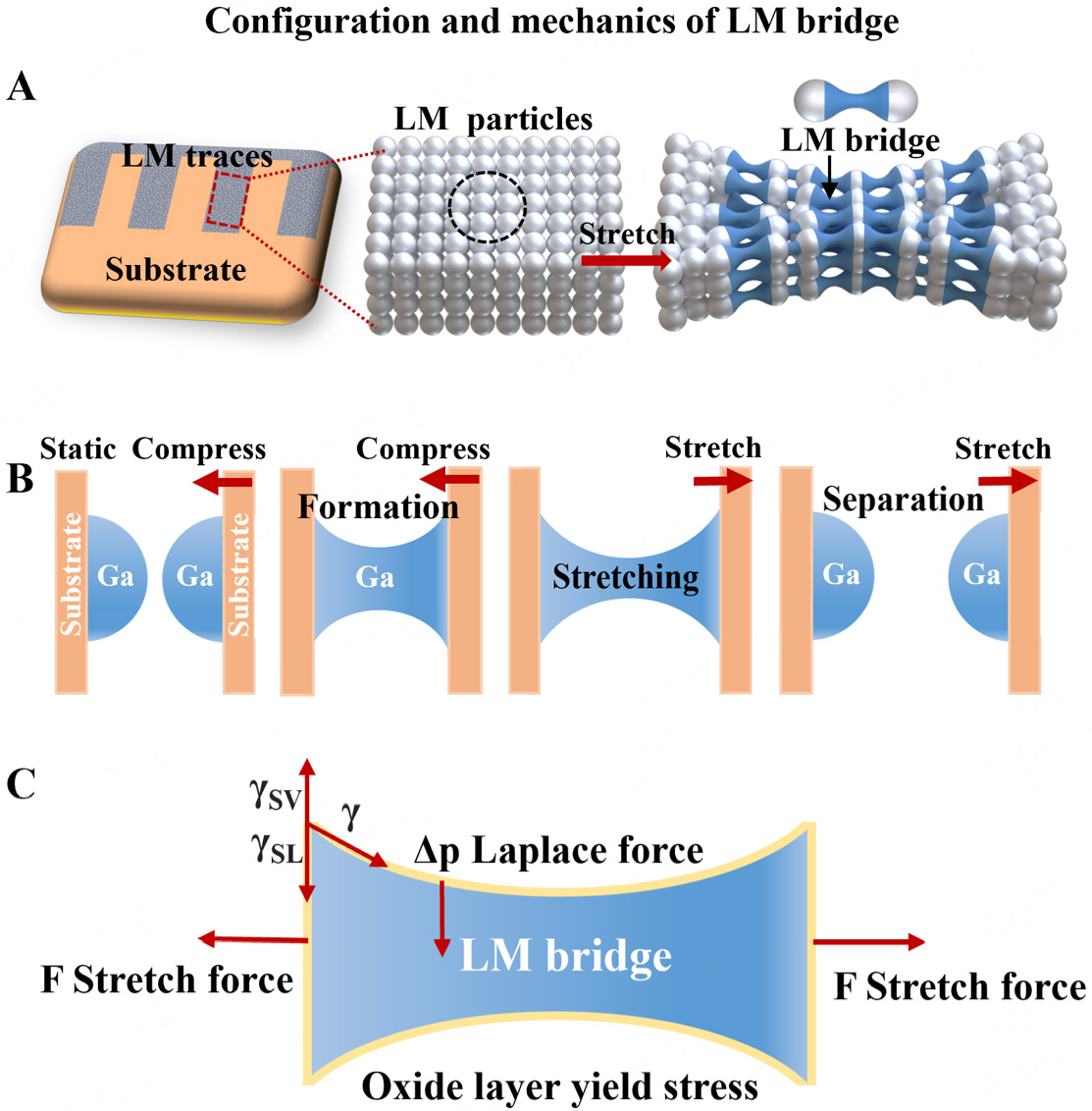

Figure 1A illustrates the construction of a typical flexible conductive circuit, where LM NDs dynamically reshape under deformation and form liquid bridges through interconnecting adjacent droplets, thereby establishing a continuous conductive network. The fluidity of LM bridges yields good stretchability while their rupture disrupts conductivity, making the stability of LM bridges a key factor for the performance of flexible electronics. The shape evolution of LM ND under applied stress is demonstrated in Figure 1B, highlighting the transition from initial droplet state to bridge formation and eventual separation during stretching. Multiple competing forces, including Laplace pressure, external stretching forces, and interfacial tension, govern this deformation process [Figure 1C]. Among these, solid-liquid interfacial tension and the associated wetting behavior obviously influence the elongation of LM bridges, which critically affects the mechanical and electrical stability. More importantly, the presence of an oxide layer at the surface (considered as a liquid-gas interface) of LM ND introduces further complexity to the dynamic evolution of LM bridges due to the influence of variation of surface tension and viscoelasticity. The oxide layer’s thickness and dynamic change determine whether it enhances bridge stretchability or restricts deformation by reducing LM’s fluidity. Therefore, key parameters including interfacial wettability, oxide layer properties, and force balance should be considered for precise control over the LM bridge in stretchable electronics.

Figure 1. Configuration and mechanics of the LM bridge in flexible electronics. (A) Schematic of LM NDs forming interconnected liquid bridges under stretch to enable conductive flexible circuits. (B) Sequential illustrations of the formation and separation process of the LM bridge. (C) Force balance diagram of the liquid bridge during stretching, highlighting the interplay of Laplace pressure, external stretching forces, and interfacial tension.

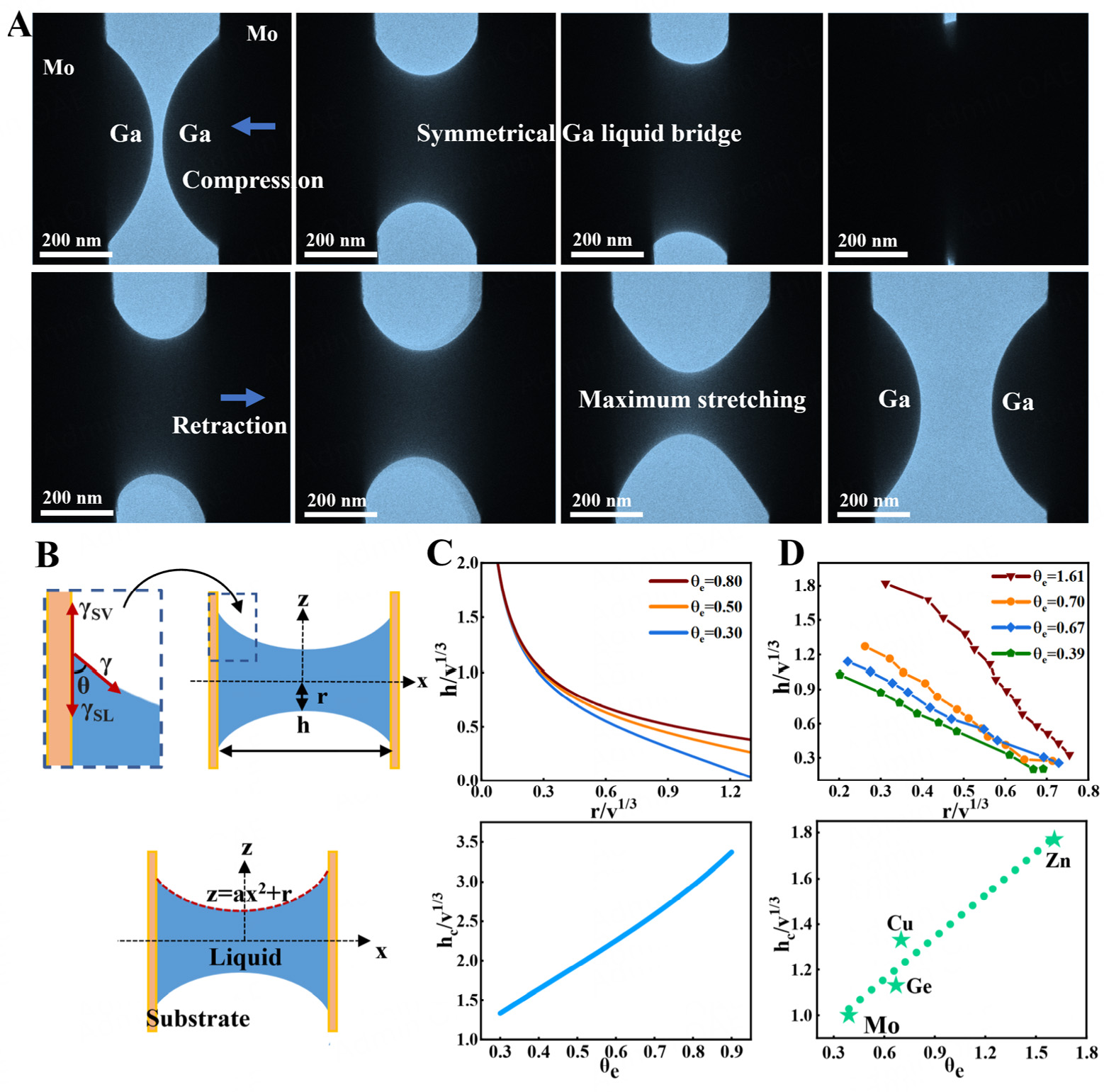

To clarify the influence of the liquid-solid interface on the shape evolution of LM NDs, in situ TEM experiments were conducted by compressing and stretching LM NDs between two solid metal substrates. This approach enabled real-time observation of the formation and morphological evolution of the LM bridge. The LM ND is pure Gallium, which typically exhibits a core-shell structure consisting of a liquid core enclosed by an oxide layer shell. It should be noted that an unevenly distributed surface oxide layer can lead to the formation of irregular LM bridges. To achieve a symmetrical and well-defined LM bridge, the oxide layer was removed by repeatedly pressing the LM ND against a clean substrate

Figure 2. Influence of solid-liquid interfacial wettability on LM bridge evolution. (A) In situ TEM images of the dynamic formation, elongation, and breakup of an LM bridge between Mo substrates. (B) Theoretical model of the LM bridge, where the equilibrium wetting angle θe satisfies Young’s equation and the shape follows a parabolic equation. (C) Theoretical predictions of normalized elongation h/V1/3 vs. normalized radius r/V1/3 and maximum stretching length hc vs. wetting angle θe for varying wettability conditions. (D) Experimental validation on Mo, Ge, Cu, and Zn substrates, showing normalized elongation h/V1/3 vs. radius r/V1/3 and maximum stretching length (hc) vs. equilibrium wetting angle θe.

To systematically investigate the effect of wettability on the deformation dynamics of the LM bridge, we examined bridge formation on various substrates, including copper (Cu), germanium (Ge), and zinc (Zn)

where θe is the equilibrium contact angle, and γSV, γSL, and γ represent the solid-vapor, solid-liquid, and liquid-vapor interfacial tensions, respectively. Additionally, we assume that the liquid bridge maintains a parabolic shape, described by z = ax2 + r [Figure 2B]. Based on these equations, we derived the evolution curves for the radius (r) at the narrowest part of the liquid bridge and the elongation (h) under different contact angle conditions (details can be found in the Experimental Section).

As illustrated in Figure 2C, for a constant ratio r/V1/3, an increase in θe results in a greater elongation h/V1/3 of the LM bridge. The corresponding plot in Figure 2C further demonstrates that the maximum stretching length (hc) of the liquid bridge increases with increasing θe, indicating the critical role of interfacial wettability in liquid bridge deformability. Based on this theoretical framework, we can deliver the evolution curves of LM bridges across four different substrates. These experimental results agree well with the simulation predictions. As shown in Figure 2D, in the curve of h/V1/3 vs. r/V1/3, where r/V1/3 remains constant, the bridge achieves its maximum elongation on the Zn substrate, followed by Cu, Ge, and Mo substrates, respectively. Furthermore, as depicted in Figure 2D, the equilibrium wetting angle and maximum stretch length of the LM bridge are optimized on the Zn substrate, with Cu, Ge, and Mo substrates exhibiting lower values.

The LM NDs exhibit better contact and enhanced deformability on metal substrates with higher wettability. Improved wettability enables the LM NDs to spread more uniformly across the substrate, overcoming the limitations imposed by high surface tension and facilitating greater elongation of the LM bridge. Under identical conditions, the LM bridge on a highly wettable substrate experiences less resistance, enabling it to stretch longer before rupture. Noting that, while simulations and experimental results generally align, discrepancies still arise due to the complex interplay between substrate properties and the wetting behavior of the liquid bridge. For example, surface roughness can introduce local variations in the contact angle, affecting bridge stability and morphology. Minor variations in substrate composition or structure can also alter surface energy, leading to inconsistencies in contact angle measurements. In addition, the contact angle of LM NDs on the substrate may exhibit hysteresis, which results in the differences between advancing and receding angles. For instance, a larger advancing angle facilitates spreading during the expansion of the LM bridge, whereas during contraction, a smaller receding angle makes retraction more difficult[31]. This asymmetry can influence the overall stability and configuration of the LM bridge, implying the importance of precise control over interfacial properties for stretchable electronic applications.

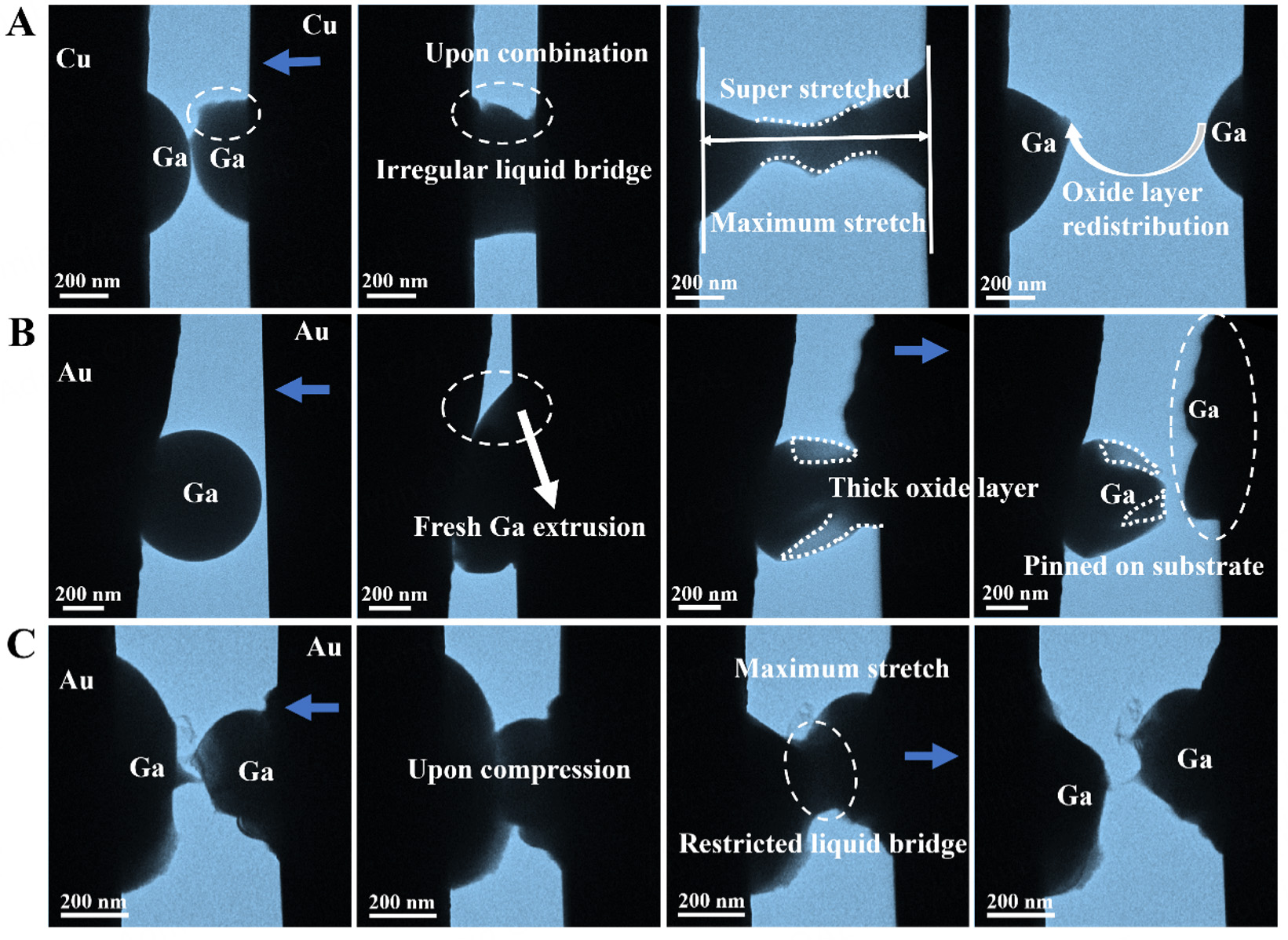

The above discussion displays the critical effect of substrate wettability on the deformability of the LM bridge, it is believed that the interaction between the surface oxide layer and the dynamic behavior of bridge deformation is important as well. Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure 4 illustrate the influence of the surface oxide layer on the deformation dynamics of the LM bridge. In the absence of a surface oxide layer, LM NDs typically adopt a spherical shape due to the high surface tension. However, the presence of a thicker oxide layer stabilizes the inner liquid by introducing yield stress, counteracting the cohesive forces of the LM NDs. This stabilization, coupled with the non-uniform distribution of the oxide layer, results in irregular morphology of NDs, with the oxide layer thickness exceeding 10 nm [Supplementary Figure 5]. Figure 3A illustrates the initial state before droplet merging, where the LM ND on the Cu tip exhibits an irregular shape due to an unevenly distributed surface oxide layer. Upon contact, the droplets do not merge immediately; instead, the solid oxide layer must first be compressed and ruptured before merging occurs. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 3A, the liquid bridge extends significantly longer than that in Supplementary Figure 2, indicating the contribution of the oxide layer. Finally, it is observed that the surface oxide layer redistributes after the bridge rupture and droplet separation.

Figure 3. Influence of liquid-gas interfacial surface oxide layer thickness on LM bridge evolution. (A) In situ TEM images of the combination and separation of two LM NDs on Cu substrate with surface oxide layer. (B) In situ TEM images of nanoindentation of an LM ND on the Au substrate illustrating irregular deformation due to a thick oxide layer. (C) In situ TEM images of the combination and separation of two LM NDs on the Au substrate with a substantially thick oxide layer, showing constrained bridge formation.

Supplementary Figure 6 presents theoretical calculations of the LM bridge deformation in the presence

Furthermore, Figure 3B and C comprehensively illustrate the impact of a substantial surface oxide layer on the dynamic deformability of the LM bridge. To investigate this effect, in situ experiments were conducted within an Au (gold) system, where an LM ND on an Au substrate was indented using an Au nanotip. The presence of a thick oxide layer results in irregular and uneven deformation, significantly affecting the droplet’s mechanical response. As shown in Figure 3B, fresh LM liquid would flow out with the rupture of the surface oxide layer during indentation. Through repeated cycling of compression and retraction, the LM ND undergoes significant morphological changes, adapting a highly irregular and non-uniform shape, accompanied by an oxide layer thickness of approximately 40 nm [Supplementary Figure 7]. Additionally, strong adhesion between LM ND and Au causes another LM ND to become pinned to the Au nanotip.

In Figure 3C, two LM NDs are used to establish an LM bridge within the Au system. Figure 3C captures the moment when droplets make contact, highlighting the difficulty of indenting the surface oxide layer until it ruptures to establish a reconnection between the LM NDs. As the bridge is stretched to its maximum length, a partial and constrained LM bridge forms, with a persistent oxide layer enveloped, which in turn limits the deformability of the bridge. The interaction between LM and Au in this system may involve a reaction that potentially forms intermetallic compounds. When LM ND and Au come into close contact, the LM ND adheres tightly and spreads across the Au surface due to the high reactivity of both materials at room temperature[33]. As a result, after much of the LM liquid is expelled, the residue on the substrate primarily consists of surface oxide layer, forming a shell-like structure. This transformation indicates a shift from a solid-liquid state to a predominantly solid state, further complicating the deformation dynamics of the liquid bridge. To further explore the role of chemical reactions, comparative experiments were conducted using fresh and passivated Cu nanotips to indent LM NDs [Supplementary Figures 8 and 9]. With a fresh Cu nanotip, extruded LM liquid adheres tightly and spreads rapidly over the tip surface

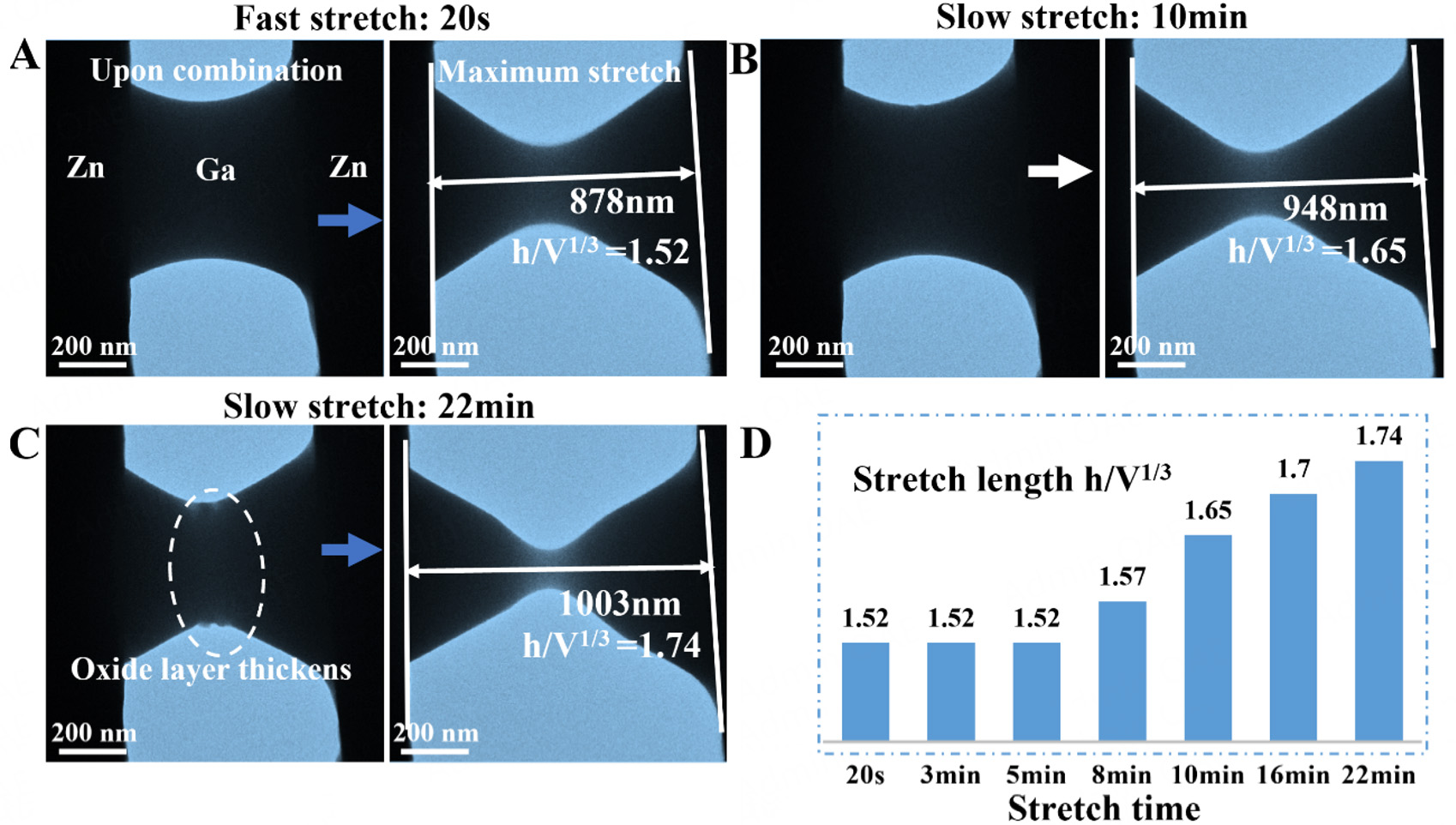

The above analysis indicates that the deformability of the LM bridge is critically dependent on the oxide layer at the interface of LM and gas. Specifically, when the oxide layer is negligible, the predominant factor governing the evolution of the liquid bridge is the wettability between LM and substrate. With a slightly thicker oxide layer, the viscoelasticity of the surface oxide layer would suppress the surface tension of the LM bridge, which may lead to an overstretched state of the bridge. However, the length of the LM bridge would be severely restricted in systems where the oxide layer is excessively thick. According to this understanding, modulation of the oxide layer thickness can be used to strategically regulate the stretching behavior of LM bridges. Thus, we chose Zn substrates as typical substrates to verify the proposed strategy. First, following a well-defined LM bridge established, the bridge is initially subjected to rapid stretching for approximately

Figure 4. Regulation of LM bridge stretching via oxide layer thickness modulation. (A) In situ TEM images of the initial and final states of the LM bridge on Zn substrate during a rapid stretch process (20 s). (B) In situ TEM images of the slow stretching process of the LM bridge at 8 min. (C) In situ TEM images of the stretching process at 22 min. (D) Statistical plot of maximum stretching length (hc) vs. stretching duration, illustrating the correlation with oxide layer growth rates.

Further increasing the stretching duration to 22 min (average stretch rate: 0.76 nm/s) leads to an enhanced elongation of the LM bridge with an irregular shape [Figure 4C], which could be attributed to the substantial growth of the oxide layer. Figure 4D illustrates the correlation between the maximum stretching length of these LM bridges and the corresponding stretching duration. For shorter stretching durations, the oxide layer growth rate remains lower than the bridge elongation rate, preventing the formation of a continuous oxide layer. Consequently, the oxide layer ruptures before significant thickening can occur, and the stretching length of the LM bridge remains unchanged. As the stretching duration increases, the growth rate of the oxide layer surpasses the stretching rate, leading to the formation of a dense oxide layer on the surface of the liquid bridge and greater bridge elongation. It is anticipated that, owing to the self-limiting effect of the surface oxide growth, further increasing the stretching duration is expected to cause the maximum stretching length to plateau, as additional oxide accumulation reduces fluidity and constrains further elongation.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study reveals the interdependent roles of substrate wettability and oxide layer dynamics in governing the deformability of LM bridges. We demonstrate that substrate wettability primarily dictates bridge formation when the oxide layer is minimal, whereas a moderate oxide layer enhances stretchability by introducing viscoelastic resistance. It can then delay the rupture of bridges and allow them to be super-stretched. However, as the oxide layer thickens further, its yield stress surpasses surface tension, restricting fluidity and ultimately inhibiting bridge formation. Furthermore, our findings show that stretching duration directly influences oxide growth, enabling precise control over liquid bridge elongation. The self-limiting nature of the oxide layer suggests that beyond a critical threshold, further thickening suppresses deformability, leading to a transition from a fluid-like to a predominantly solid-like state. These insights into liquid bridge mechanics and oxide layer modulation offer a strategic framework for optimizing the design of stretchable LM-based conductors, paving the way for their integration into advanced reconfigurable and deformable electronic systems. While our experiments focused on rigid substrates, the principles of LM bridge deformation dynamics are expected to extend to stretchable substrates, such as elastomers and hydrogels. However, conducting in-situ TEM experiments on stretchable substrates presents challenges due to their high electron beam sensitivity, which can lead to degradation and compromise imaging quality. Future studies could explore alternative characterization techniques or develop beam-resistant stretchable materials to investigate LM bridge formation in these systems.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Data curation, investigation, writing - original draft: Shu, L.

Conceptualization, investigation, supervision, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing: Cheng, N.; Ren, L.

Data curation, formal analysis, investigation: Ding, Z.

Formal analysis, methodology, software, writing - review & editing: Man, X.

Methodology, resources, writing - review & editing: Du, Y.

Investigation, methodology: Yu, H.

Conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, writing – review & editing: Ge, B.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Financial support and sponsorship

This project was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1403203), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52201003, No.52201164, No.22473005, and No. 12474001), and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (L234009).

Conflicts of interest

Prof. Du Y. is a Senior Editorial Board member of the journal Microstructures. Prof. Du Y. was not involved in any steps of editorial processing, notably including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision making, while the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Corzo, D.; Tostado-Blázquez, G.; Baran, D. Flexible electronics: status, challenges and opportunities. Front. Electron. 2020, 1, 594003.

2. Wang, P.; Hu, M.; Wang, H.; et al. The evolution of flexible electronics: from nature, beyond nature, and to nature. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2001116.

3. Li, D.; Cui, T.; Xu, Z.; et al. Designs and Applications for the multimodal flexible hybrid epidermal electronic systems. Research 2024, 7, 0424.

4. Heng, W.; Solomon, S.; Gao, W. Flexible electronics and devices as human-machine interfaces for medical robotics. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2107902.

5. Dai, Y.; Hu, H.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, S. Stretchable transistors and functional circuits for human-integrated electronics. Nat. Electron. 2021, 4, 17-29.

6. Kong, M.; Vong, M. H.; Kwak, M.; et al. Ambient printing of native oxides for ultrathin transparent flexible circuit boards. Science 2024, 385, 731-7.

7. Tong, X.; Tian, Z.; Sun, J.; Tung, V.; Kaner, R. B.; Shao, Y. Self-healing flexible/stretchable energy storage devices. Mater. Today. 2021, 44, 78-104.

8. Vallem, V.; Aggarwal, V.; Dickey, M. D. Stretchable liquid metal films with high surface area and strain invariant resistance. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201233.

9. Lin, Y.; Genzer, J.; Dickey, M. D. Attributes, fabrication, and applications of gallium-based liquid metal particles. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2000192.

10. Tang, S.; Tabor, C.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Dickey, M. D. Gallium liquid metal: the devil's elixir. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2021, 51, 381-408.

11. Ding, Y.; Zeng, M.; Fu, L. Surface chemistry of gallium-based liquid metals. Matter 2020, 3, 1477-506.

12. Yao, B.; Lü, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Ultrasensitive, highly stable, and stretchable strain sensor using gated liquid metal channel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2314298.

13. Han, S.; Kim, K.; Lee, S. Y.; Moon, S.; Lee, J. Y. Stretchable electrodes based on over-layered liquid metal networks. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2210112.

14. Shi, C.; Zou, Z.; Lei, Z.; et al. Stretchable, rehealable, recyclable, and reconfigurable integrated strain sensor for joint motion and respiration monitoring. Research 2021, 2021, 9846036.

15. Style, R. W.; Tutika, R.; Kim, J. Y.; Bartlett, M. D. Solid-liquid composites for soft multifunctional materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2005804.

16. Ai, L.; Lin, W.; Cao, C.; et al. Tough soldering for stretchable electronics by small-molecule modulated interfacial assemblies. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7723.

17. Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Cole, T.; et al. 3D-printed liquid metal polymer composites as NIR-responsive 4D printing soft robot. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7815.

18. Lee, S.; Jaseem, S. A.; Atar, N.; et al. Connecting the dots: sintering of liquid metal particles for soft and stretchable conductors. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 3551-85.

19. Lee, W.; Kim, H.; Kang, I.; et al. Universal assembly of liquid metal particles in polymers enables elastic printed circuit board. Science 2022, 378, 637-41.

20. Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, R.; Rao, W.; Liu, J. Liquid metal composites. Matter 2020, 2, 1446-80.

21. Silva, C. A.; lv, J.; Yin, L.; et al. Liquid metal based island-bridge architectures for all printed stretchable electrochemical devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002041.

22. Li, W.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Ultrastrong MXene film induced by sequential bridging with liquid metal. Science 2024, 385, 62-8.

23. Kim, J.; Lee, J. Liquid-suspended and liquid-bridged liquid metal microdroplets. Small 2022, 18, e2108069.

24. Hu, Y.; Zhuo, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Graphene oxide encapsulating liquid metal to toughen hydrogel. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2106761.

25. Handschuh-wang, S.; Zhu, L.; Gan, T.; Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Zhou, X. Interfacing of surfaces with gallium-based liquid metals - approaches for mitigation and augmentation of liquid metal adhesion on surfaces. Appl. Mater. Today. 2020, 21, 100868.

26. Xu, J.; Guo, H.; Ding, H.; et al. Printable and recyclable conductive ink based on a liquid metal with excellent surface wettability for flexible electronics. ACS. Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 7443-52.

27. Cheng, J.; Shang, J.; Yang, S.; Dou, J.; Shi, X.; Jiang, X. Wet-adhesive elastomer for liquid metal-based conformal epidermal electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200444.

28. Style, R. W.; Boltyanskiy, R.; Allen, B.; et al. Stiffening solids with liquid inclusions. Nature. Phys. 2015, 11, 82-7.

30. Seveno, D.; Blake, T. D.; De Coninck, J. Young's equation at the nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 096101.

31. Butt, H.; Liu, J.; Koynov, K.; et al. Contact angle hysteresis. Curr. Opi. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2022, 59, 101574.

32. He, Y.; You, J.; Dickey, M. D.; Wang, X. Controllable flow and manipulation of liquid metals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309614.

33. Choi, H.; Sohn, Y. Interfacial reactions between liquid Ga and solid Au. Mater. Lett. 2023, 330, 133220.

Cite This Article

How to Cite

Download Citation

Export Citation File:

Type of Import

Tips on Downloading Citation

Citation Manager File Format

Type of Import

Direct Import: When the Direct Import option is selected (the default state), a dialogue box will give you the option to Save or Open the downloaded citation data. Choosing Open will either launch your citation manager or give you a choice of applications with which to use the metadata. The Save option saves the file locally for later use.

Indirect Import: When the Indirect Import option is selected, the metadata is displayed and may be copied and pasted as needed.

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.